Interview

Models of Thinking

Alfredo Jaar interviewed by Kathy Battista

Kathy Battista: Could you describe your work for the Liverpool Biennial?

Alfredo Jaar: I have created a new piece titled The Marx Lounge and it is sited in a large empty storefront in the centre of Liverpool (Reviews AM341). There are too many of these around, it is quite depressing and sad. It consists of a salon painted all red, including a red carpet, black sofas and a large 8x2m table that contains 1,500 books by Marx as well as subsequent writers, theorists and philosophers. As you know, there has been a renewed interest in Marx because of the financial crisis. I wanted to offer a larger audience the extraordinary amount of knowledge that has been created in the past few decades. I believe an intellectual revolution has been going on for the past 20 or 30 years, but I also see an extraordinary gap between this intellectual revolution and the real world. So I wanted to ask, why is this? Is this gap a symptom of the difficulty of apprehending this new knowledge, or is it in the interests of the status quo to keep it the way it is? I am afraid it is a little of both. Besides hundreds of books by and about Marx, you will find political theorists and philosophers like Zizek, Hall, Rancière, Butler, Laclau, Mouffe, Jameson, Bourdieu, Fanon etc. For me these writings offer us models of thinking the world. And that is what I try do as an artist – I create models of thinking. I view The Marx Lounge as a space of resistance, or as David Harvey would call it, a space of hope.

KB: It resembles an architectural model of a city.

AJ: I was thinking about an architectural model, what might the architecture of knowledge look like. But in the end it is a reading room, a very focused library.

KB: Do you think your work is most appropriate in a biennale context rather than a commercial setting?

AJ: I consider myself an architect making art and most of my practice is site-specific. In the past 30 years I have divided my work into three distinct areas and only one-third of my practice takes place in museums, galleries, what we call the art world. But because of its extraordinary insularity – it is a small world in which we mostly talk to each other – I decided to get out.

That is why in another third of my practice I create public interventions. These are actions, performances, events that take place in places and communities far removed from the art world where the audience is not well-versed in the vocabulary of contemporary art. So you have to create, to communicate using a new language, a different language. I like the challenge of talking to a different type of audience.

The third part is teaching. I give talks and direct seminars where I share my experience with the new generation from whom I learn enormously. It is a real exchange. I feel complete, as a professional but also as a human being, only by doing these three things at the same time. The Liverpool Biennial context, like most biennales, has the potential to go beyond our little art world and reach larger audiences, and it has a strong education component.

KB: The three categories implode in The Marx Lounge.

AJ: Absolutely. This is clearly a work where these three categories/ audiences overlap in the most perfect way.

KB: Was the work acquired by the Liverpool Biennial or by Tate?

AJ: The economics of my strategy have always been the same with all institutions. Liverpool Biennial paid for the production of the work but I own it. If it ever gets sold, I will return the production money to the Biennial. This way they can finance another work by another artist. Money must circulate.

In the case of this particular production, because there are three copies of each title, in a way I potentially own three Marx Lounges and what I do with these three sets afterwards is a fundamental aspect of the piece.

Because of the reckless funding cuts being implemented now in the UK, there is a great deal of resistance but also some initiatives in England to do with creating places of study. In Liverpool there is a group of intellectuals trying to create the Free Liverpool University. I am planning to possibly donate one of the Marx Lounges to this new young institution, where they will hopefully recreate it and make it grow – a living library. For the other two sets we are looking at poor, underfunded libraries in marginalised communities.

KB: Is there a special arrangement for the books, such as alphabetical or chronological?

AJ: What I did was try to place Marx in all areas of the table and then organise some ‘short circuits’ between titles and authors, suggesting different connections or oppositions. We also included the Communist Manifesto in all the languages of the so-called ‘minority populations’ of Liverpool.

Parallel to The Marx Lounge I have organised a series of public discussions, encounters between a political theorist and someone from the art world. David Harvey and Ivet Curlin participated in the first dialogue. Last week we had Chantal Mouffe and Mark Sealy.

I also created an advertising campaign in Liverpool streets with posters and billboards that say ‘Culture = Capital’ and announcing The Marx Lounge. I believe we must insist that culture is the real capital. If the state can produce money to reward irresponsible, criminal banking, then it can and should produce money to create culture. A living culture is one that creates. If the UK has any visibility in the world it is thanks to its artists and intellectuals and cultural institutions and universities. It is not because of its banks.

KB: Do you think this relates to your Documenta piece?

AJ: I think all my works relate to each other one way or another. The Documenta piece focused on the blindness of our society. Here in a way it is a reverse situation – I am confronting the audience with this huge body of knowledge that exists, but that we do not know how to use. This is the dilemma we face as cultural producers or artists – we speculate, we dream, we invent, we create and then there is this huge extraordinary gap between our productions and the real world. How do we close that gap?

KB: How does your background in architecture play a role in your art practice?

AJ: Architecture is a tool that I apply in every single work to articulate the ideas of the project. For me a project is foremost a thinking process. Perhaps 90% of the process is about thinking and the last 10% is about articulating that into a visible work. That is when I use the language of architecture – scale, light, movement, space, tension. As an architect, I look at a site not only as a physical space but most importantly as a political space, as a social space, as a cultural space.

KB: Was studying architecture in Pinochet’s Chile part of a dream of transforming society?

AJ: I always wanted to be an artist. My father thought it was a very bad idea. So the compromise was architecture because he thought I might be able to make a living that way. My father never in his wildest dreams imagined that I could make a living as an artist and, in Chile 30 years ago, I didn’t believe it either. But I feel extremely lucky that I never studied art and became an architect instead. In a way I don’t know what art is. And this pushes me in creative directions trying to invent it. Working with students I have realised how they have been inserted into a pre-set framework of thinking about what art is. They tend to naturally follow certain existing aesthetic formulas.

I have this extraordinary freedom. If you look at my work of the past ten years you might think these are 100 works by 100 different artists. I am not seeking to have a branded look. I am more interested in developing and articulating ideas. Of course that makes the work quite difficult in terms of its marketability.

KB: Yet you do work with commercial galleries.

AJ: I have a very slow relationship with galleries in that I show with them every three, four or five years. It is not the normal commercial rhythm and this has to do with the slowness of my process and perhaps my resistance to that world. I think I have always had a schizophrenic relationship to the art world. But I do not reject that audience at all. It represents a third of my practice. I think we have to use every space available.

KB: One element I was interested in concerning your work is the concept of beauty. You deal with so many topics – from genocide to gold-mining – yet the visual remains paramount. Is it ever a concern in your work that it could become too beautiful?

AJ: I am not afraid of beauty. That upsets a lot of my critics. On the contrary I think beauty should be part of the language we use in order to communicate our ideas. It is an essential constitutive element of my work. But I am not referring to visual beauty only. I think that concepts can be very beautiful. Sometimes the truth is incredibly beautiful. The artist defines what is beauty. The artist invents it. What is difficult is to find that perfect balance between content and spectacle. Most of the time I fail and the work is either too didactic or too beautiful. Hopefully so far in very few works of mine the audience gets everything at once – they are informed, they are moved, touched, illuminated and they will leave changed. That is a lot to demand of a single work and that is very difficult to achieve, almost impossible.

KB: Beauty is also an abiding issue in photojournalism, which is something that you have been interested in throughout your career. I thought of your work when the trapped Chilean miners were in the media recently.

AJ: The rescue was absolutely controlled and manipulated for political gains. The government took over all aspects of the operation to an extraordinary degree. If you followed the rescue on TV, you could see the government logo on the top left corner of the screen. I had never seen this kind of blatant ownership of the image. It was totally unnecessary as we knew the government was in charge.

But everyone involved tried to do the same. The company that did the final drilling to reach the miners – the day before they completed the passageway that would finally bring them up – sent T-shirts down with their logos asking the miners to wear them. So when they filmed that extraordinary moment, all 33 miners were wearing the same T-shirt with their logo. Thankfully – and ironically – when the government saw these images and understood what had happened, they wouldn’t release that footage. There are no public images of the miners celebrating. I would give a lot to get that tape.

When the miners suffered this accident, the relatives spontaneously put 33 flags in the desert near the mine in commemoration of their lives. They didn’t know at that time if they were alive. Each flag was dedicated to one of the miners.

In 1981 I did a piece called Chile 1981, before leaving where I divided the country with a thousand flags from the mountains to the sea. The line divided Chile in half. I wanted to articulate the dramatic division of the country under Pinochet. At the time half of the country wanted the return of democracy, but the other half was perfectly happy with Pinochet. The two sides were brutally divided and I was suffocated by the military dictatorship and I wanted to leave with a powerful public statement.

The flags end in the sea as I wanted to articulate the idea that the country was practically committing suicide because no communication was possible between the two sides. This work also had another connotation. There were rumours at the time that the Pinochet regime was killing its opponents, by throwing them alive into water with weights at their feet or burying them alive in the desert. Unfortunately, later we learned that it was true. So that piece had a certain reading at the time, but it acquired a different reading when we learned the truth.

When this mining accident occurred – and the flags were back in the desert – people couldn’t believe it. But the beauty is that they were found alive and they were brought back to life, something we couldn’t do with the Pinochet victims.

KB: Would it have been frowned upon to make a work like that in Chile in 1981?

AJ: During the military regime we learned as artists how to speak a poetic language. We practised self-censorship. We knew if we crossed a line we would be in danger of being ‘disappeared’. The regime killed almost 4,000 people. If we wanted to participate in exhibitions we had to learn how to express what we wanted to say, but in a way that would be unreadable to the authorities. My use of metaphors and poetic devices started in those years in Chile. I also had no choice.

Another recent work of mine is a memorial for the victims of the Pinochet regime in Chile. Michelle Bachelet, who ended her mandate in March of this year, was the first female socialist president of Chile. As part of her legacy she created the Museum of Memory and Human Rights where the story of the 17-year dictatorship is told. There was an international competition and a group of architects from São Paulo won. It is a very striking building with a façade covered in copper, which is what the miners were looking for in the north. The entire economy of Chile revolves around copper.

The building is a huge volume that sits on two reflecting pools. It creates a large plaza where one can walk underneath the building. I was commissioned to create the memorial for the victims of the regime somewhere in the plaza. When I studied the proposal and saw the space they had built I thought I couldn’t compete with this building and that whatever I put outside would be totally ridiculous. So instead of going up like the architects I am going to go down.

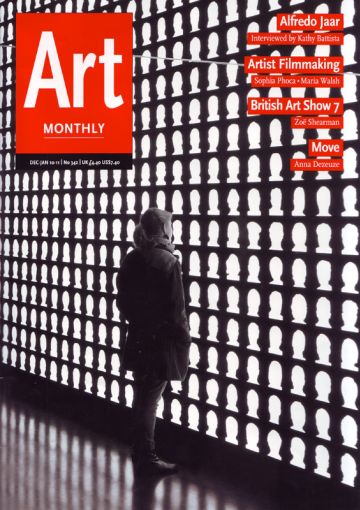

The entrance to my space is 20m away from the entrance to the museum. People walk down 33 steps to reach a level of 6m underground. So the title of the work is La Geometria de la Conciencia, which means The Geometry of Conscience. The piece consists of the subtle graduation of light. You first reach a 5m-square plateau. Even though it is still in the open air the light is filtered by the depth. Here you face the entrance, which is minimal. Once you enter the second space, which is also 5m square, there is nothing – just concrete walls and floor. The only light is indirect, coming from the two side doors. There is a museum guide who welcomes you and explains that you will enter a third cubic space where you will spend three minutes inside, that the door will close automatically, and that you have to turn off your phone and remain silent. A maximum of ten people are allowed.

Finally you go in and the door closes automatically behind you and you find yourself in full darkness for one minute. (The guard has explained that there is a panic button if there is an emergency and you need to get out.) After a while your eyes get used to the darkness and you start seeing silhouettes on the back wall. The silhouettes are all different. There are two kinds – half of them are victims of the Pinochet regime, the others are anonymous Chileans whom I photographed on the streets of Santiago. But they are mixed up. People can perfectly recognise relatives or loved ones, other people just see silhouettes. After 60 seconds of darkness, the lights come on and gradually intensify. It takes 90 seconds to go from 10% to full intensity. When you get used to the blinding light you realise that both side walls are mirrored, which creates an infinite wall on both sides. You are illuminated historically, conceptually, physically and emotionally by the faces of the living and the dead.

I wanted to suggest that this monument was not only for the 4,000 people who died under Pinochet. This is a monument for all Chileans. Instead of marginalising the victims like most memorials do, I wanted to integrate them into a collective narrative. We are all together, I wanted to suggest. This is a monument for 17 million Chileans alive and dead. I thought hard about how in memorials the victims are always marginalised. We create these crypts or mausoleums and bury them there as if to get rid of them. Logically there is always resentment from the relatives who feel that society has never really understood their pain. I wanted to suggest another paradigm for memorials.

KB: It also implicates the viewer.

AJ: Yes, because we are absolutely part of it. After 90 seconds the lights go off again and you remain in the dark for 30 seconds before the doors open. During that time you will experience an after-image effect and you still see the silhouettes in the dark as they are imprinted in your retina and that is a possible way to take them with you. It is a permanent memorial. I felt free because the museum is there and will tell the official story. They have the faces, names, stories, documents – the historical narrative.

I am now designing a memorial for the victims of the genocide in Rwanda so I have had to visit a lot of memorials. Most of them are grey and depressing. That is why I wanted to invite the living into these spaces and the light. That is why I dared to shift the paradigm and hoped that it would go somewhere. I couldn’t sleep for months. I have made maybe 60 public interventions and most of them are ephemeral – you use the city as a laboratory and if you fail it goes away after a while. This was going to stay forever.

KB: How much do you identify yourself as a Latin American artist? Do you feel that being from Chile allows you a platform to deal with issues that a western artist might not be able to?

AJ: Well, I feel incredibly free, not because I am Chilean, but because I am not afraid to express my point of view and invite people into different worlds that I create. You have asked a fascinating question because when I arrived here in New York it was a huge disadvantage to be from Chile. Thirty years ago the art world was incredibly provincial and an international exhibition included a few Americans and a few Germans. It was very difficult to break in and nobody really cared about artists from other places. We were totally invisible. So when you ask me if it is an advantage I want to believe that things have changed. For me the world of art and culture is perhaps the last remaining space of freedom. And I exercise my freedom fully. We must because we don’t know how long it will last.

KB: It is interesting to see how mainstream institutions today are embracing Latin American artists.

AJ: I think there are extraordinary artists in Latin America – like everywhere else – and of course the establishment needs new blood. I’m glad that these institutions have opened their doors to artists and intellectuals from other places, but the change is only on the surface. We need more radical, structural changes. The canon is still one and the same – the practice and production of these artists are seen as just adding to it. But a lot of progress has taken place.

KB: Latin American art has such an impressive body of scholarship around it already.

AJ: Latin America has always been there. We were just invisible. If you look at the development of conceptual art there were extraordinary concurrent developments there and here and sometimes we were the avant-garde, but we were ignored because history was written here in the US. There are people trying to change that, but it will take perhaps another generation to create structural changes.

KB: Can you comment on your work with film and video?

AJ: When I was completing my fifth year of architecture studies Santiago was being redeveloped in the most horrible way. A lot of ugly apartments were being built as part of the neoliberal economy that Pinochet was imposing without any possible resistance. I abandoned architecture and went to study filmmaking. After I completed my film studies, I decided to go back and complete my architecture degree because I had discovered how connected film and architecture were.

I am a frustrated filmmaker. All my works have this filmic quality that I can’t avoid because I am thinking about film all the time. I have managed to create quite a few short films. I released a film last year, The Ashes of Pasolini, at the Venice Biennale (Reviews AM328). If someone would give me the funding I would immediately stop everything and do my first film. Film is perhaps the most complete language in which to express yourself. I envy the communication that you reach with an audience in a cinema. As you know, in the art world the average time the spectator spends with an artwork is three seconds. We work three years on a project, we finally install it somewhere and people walk by, casually. That is a tremendous frustration.

KB: What kind of film would you make?

AJ: I have written a few script ideas. The ideas are fictional films, but of course based on reality. It would be in the same spirit of what I do as an artist but trying to reach a large audience because I don’t want to make a film seen by 30 people.

Alfredo Jaar is an artist based in New York. Forthcoming exhibitions include Galerie Kamel Mennour, Paris, and Sharjah Biennale.

Kathy Battista is director of contemporary art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, New York.

First published in Art Monthly 342: Dec-Jan 10-11.