Michael O’Pray Writing Prize

Looking at Palestine

Nevan Spier views Palestine through the films of Mustafa Abu Ali and Elia Suleiman

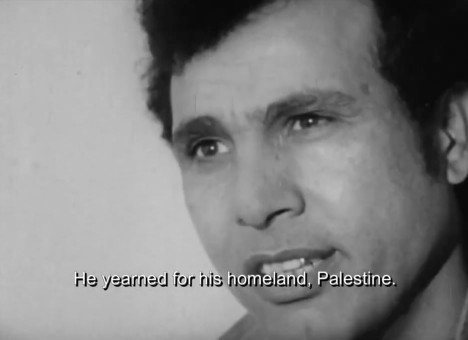

Mustafa Abu Ali, Palestine in the Eye, 1976

i.

Palestine in the Eye, 1976, is a 28-minute documentary by Palestinian resistance filmmaker Mustafa Abu Ali that commemorates the legacy of his friend and collaborator, Hani Jawharieh, who was killed earlier that year at the age of 37 while filming combat in Ain Toura, Lebanon. The film features 16mm footage shot by Jawhariah, including a handful of sequences captured moments before he was fatally struck by shrapnel, as well as scenes from his funeral, an interview with his widow, Hind Jawharieh, and tributes from his friends and colleagues. A brief excerpt from a film festival comprises the only footage of Jawharieh himself, showing him as he defends the importance of filmmaking for the Palestinian revolutionary cause. Despite its title, almost all of the events in the film take place outside Palestine.

ii.

In the year prior to the establishment of Israel, the United Nations issued a proposal for the partition of Palestine. The ensuing 1948 Arab–Israeli war, also known as the Nakba, resulted in the forced displacement of over 700,000 Palestinians. By the end of the war, only the West Bank and the Gaza Strip remained outside Israeli control. Then, in 1967, Israel’s illegal occupation of these territories exiled hundreds of thousands more Palestinians; most fled to Jordan, where the following year Abu Ali and Jawharieh, alongside photographer Sulafa Jadalla, co-founded the Palestine Film Unit (PFU) with the aim of documenting and archiving the Israeli attacks against exiled Palestinians and the armed struggle of Palestinian militant groups.

The PFU’s watchful ethos was unknowingly echoed decades later in the ‘All Eyes on Rafah’ slogan that went viral on social media in response to Israeli’s attacks in Gaza in May. At the time, Rafah housed nearly half of Gaza’s population following to mass evacuations in other parts of the strip. In Susan Sontag’s 2003 essay ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’, the author examines a similar plea to witness the full scale of war’s horrors, to resist the temptation of looking away in the face of humanity’s most cruel images. Among several examples, she cites captions in Francisco Goya’s ‘The Disasters of War’ series of etchings: ‘One can’t look’; ‘This is too much!’; or simply, ‘Why?’. In the preface to Hamid Dabashi’s collection of essays Dreams of a Nation, Edward Said writes that ‘the whole history of the Palestinian struggle has to do with the desire to be visible’. What can the films of Palestine tell us about that which we are so desperately trying to see?

iii.

Chronicle of a Disappearance, 1996, follows Palestinian director Elia Suleiman in his return to Nazareth after living in exile between London and New York for several years. Snapshots of daily life capture Suleiman as silent protagonist and reactionless observer to his surroundings while some of his family members play themselves on screen. The fragmented narrative is underscored by a sense of unease, perhaps due to the combination of fixed cameras and blocking that results in ‘actors’ entering and exiting the scene as if on stage. This initial collection of mundane moments – the preparing of food, the frequent squabbles outside a fishmonger, the afternoon naps, the tourists passing by a souvenir shop – all takes place in Nazareth, which predominantly houses the Arab population that was displaced from nearby Galilee and Haifa during the Nakba. The narrative ramps up into a swifter and more comical pace when Suleiman heads to East Jerusalem. In one memorable gag, he is invited to speak on stage about his work as a director. Every time he nears the microphone, however, feedback rings through the speakers and prevents him from speaking. The AV technician uselessly rushes back and forth, but the audience has already lost all interest. East Jerusalem has been occupied by Israel since 1967, despite being internationally recognised as part of the West Bank of Palestine.

iv.

The fragmentation of the Palestinian territory is reinforced by the restriction of movement imposed on those seeking to travel between the West Bank and Gaza. Palestinian residents must contend with roadblocks, armed borders, checkpoints and the persistent threat of violence. Unsurprisingly, it is remarkably difficult for Palestinian filmmakers, both in the diaspora and in Palestine, to produce and distribute their works. For Palestinian cinema, Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 marked not only a shift towards favouring fictional works instead of documentaries, but also the near complete loss of the materials held by the PFU in Beirut. One work that has survived is Palestine in the Eye, which was restored by filmmaker Azza El-Hassan as part of her project to uncover the lost archives. A limited amount of Jawharieh’s filmography, consisting of reels salvaged by his widow before she fled to Jordan, also survive.

v.

They Do Not Exist, 1974, perhaps Abu Ali’s most famous film, opens with scenes of children playing outside their homes in the Nabatieh refugee camp, 70km south of Beirut, which housed more than 6,000 people. A ten-year-old girl named Aida writes a letter to a freedom fighter retelling daily life at the camp. She apologises for the humble gift enclosed: a towel. She says she has five brothers, and that her father is a carpenter. In May 1974, Israel bombed almost the entirety of the Nabatieh camp to the ground. Abu Ali interviews some of the residents in the film: they describe digging through the rubble for their children’s bodies. The film takes its title from a 1969 Sunday Times interview with then Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir which echoes the Zionist erasure of a unified Palestinian identity pre-1948. Similar tactics of dehumanisation and objectification of indigenous populations have often been employed by other settler colonial states in order to legitimise ethnic cleansing and the siege of land.

vi.

Introduction to the End of an Argument, 1990, is a 40-minute experimental film by Elia Suleiman and Jayce Salloum. A montage of TV programmes, Hollywood titles, Israeli tourism propaganda and racist caricatures of Palestinians and Arab people, it features the likes of Henry Kissinger, George W Bush and Benjamin Netanyahu, as well as excerpts from films such as Lawrence of Arabia, 1962, and The Delta Force, 1986. Divided into chapters of titles that repeat themselves multiple times, the film instils a sense of being stuck, of being tethered to an unending nightmare. In a snippet of a US news report, Palestinians are likened to unwanted pests through the eyes of the settler: ‘what they found was a hostile land filled with snakes, and scorpions, and Arabs’. At the time of writing, more than 40,000 Palestinians have been killed since the start of the Israeli invasion of Gaza in response to the Hamas attack of 7 October 2023. Nearly the entirety of Gaza’s 2.3 million population has been forcibly displaced.

vii.

A glance back at Abu Ali’s and Suleiman’s films from the 1970s and 1990s reveals not only the importance of Palestinian visibility, but more specifically the responsibility of non-Palestinians in the face of witnessing the annihilation of a people over the course of a century. How many times do we still encounter justifications for the war crimes committed against the people of Palestine, and how often do survivors of Israeli bombings, such as those from 1974’s Nabatieh refugee camp, still delve through rubble in search of the bodies of their loved ones? What about the estrangement of diasporic Palestinians, now exceeding seven million, as depicted by Suleiman in Chronicle of a Disappearance? How does Hani Jawharieh’s death in 1976, captured by him on camera in the hills of Lebanon, continue on our social media feeds via the images of those that are murdered every week?

The struggle for liberation and the preservation of culture have been the bedrock of Palestinian filmmaking since its foundation. For non-Palestinians, however, idle consumption of such films, no matter how revolutionary their plight, has never been enough. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag writes that ‘for a long time, some people believed that if the horror could be made vivid enough, most people would finally take in the outrageousness, the insanity of war’. She goes on to claim that as witnesses, we are fated to slump into complacency if we fail to concretely act on our compassion. For real solidarity with Palestine, may we find whatever means within our power to advocate, to aid and to resist. May we challenge our complicit governments and demand the defunding of the military machine that upholds Zionist occupation. If we are at all touched, moved or enraged by the films of Palestine, may it stir us into action.

Nevan Spier is an awardee of the Film and Video Umbrella and Art Monthly Michael O’Pray Prize 2024.

The Michael O’Pray Prize is a Film and Video Umbrella initiative in partnership with Art Monthly, supported by University of East London and Arts Council England.

2024 Selection Panel

- Terry Bailey, senior lecturer, programme leader, Creative and Professional Writing, University of East London

- Alice Hattrick, writer, lecturer and author of ‘Ill Feelings’

- Ghislaine Leung, Turner Prize-nominated artist

- Chris McCormack, associate editor, Art Monthly

- Angelica Sule, director, Film and Video Umbrella