Feature

Talkin’ ’bout their g-g-g-generation

Richard Grayson on the ends of post-internet art

In a recent issue, Morgan Quaintance heralded the end of ‘post-internet art’ (‘Right Shift’, AM387). This movement, he writes, is ‘recognised as the first bottom-up contemporary movement of the 21st century ... founded on an unquestioning and uncritical acceptance of the digitisation of the world narrative. Initially this was perhaps a heroically avant-garde stand against the irrationally net-averse, mid-noughties art world’. ‘Now,’ he continues, ‘it has become ideological quicksand, pulling an inert style down into the stale muck of inconsequence. Put simply, post-internet art – purportedly, art made on or off the web, primarily influenced by or dealing with the socio-cultural effects and affects of the internet – has come to its end.’

This recognition of redundancy, as described by Quaintance, may well bring the activities of artists and writers involved to a considered and gradual halt, but post-internet art is a creation of the institutions as much as it is of artists, and this may ensure that it has a continuing and awful half-life even after its end. ‘The first bottom-up contemporary movement of the 21st century’ has become hot not only because of what it is about, but also because it has qualities and attributes that effectively match the foundation myths and rhetoric of institutions, curators and collectors. This art world remains only tangentially and fleetingly interested in either the technology or the social, political and psychic effects of its operations; it remains ‘irrationally net averse’ (outside the marketing and education departments of its institutions). But, when you look at ways that the post-internet practices and artists are being framed and articulated, it becomes clear that it is precisely because these areas of digital experience are seen as unknowable and exotic that post-internet art is gaining such traction.

The name signals its oxymoronic qualities: we are not ‘post’ the internet in any discernible sense – it is still there, all around us (at least if we are anglophones with mobile phones in the West). And we are using it all the time, in fact a central riff running through the concept is the ubiquity of the internet. But although seemingly a fiction in this context, ‘post’ does nominate a shift, a rupture, a break with a past, a rupture that makes it irresistible to the romantic teleological narratives in the contemporary art world that require the constant identification of new ruptures. The curators’ rationale for ‘Art, Post Internet’ – curated by Karen Archey and Robin Peckham at UCCA Beijing in 2014 – describes post-internet artwork as being ‘consciously created in a milieu that assumes the centrality of the network, and that often takes everything from the physical bits to the social ramifications of the internet as fodder. From the changing nature of the image to the circulation of cultural objects, from the politics of participation to new understandings of materiality, the interventions presented under this rubric attempt nothing short of the redefinition of art for the age of the internet.’

So the post-internet started in 1989, when Tim Berners-Lee in the Cern Laboratories in France had the notion of combining hypertext with the transmission control protocol and the domain name system to invent the world wide web. 1989 was also the year of the final collapse of the command economies of the communist bloc and the end of the Cold War, events which allowed capitalism to become the only game in town.

Those who have been following the long engagement of artists working with the networked and the digital may ask why this interest is happening now. Artists, programmers, writers and thinkers have been involved in a radical exploration and critique of information technologies for decades, to the – to date – blanket indifference of mainstream arbiters and exhibitors of contemporary art. However, rather than being articulated and (dis)embodied in shifting and novel media of the computer and the internet, as much of the earlier work was, this current wave of production tends towards objecthood and looks pretty much like ‘art’ – be this scattery sculpture, manifesto-type text, anorexic design or French post-pop assemblage-type art. In the cases where technology is in your face – the camera-phone YouTube aesthetic of Ryan Trecartin’s installations or the shiny CGI videos of Ed Atkins – it is not as an exploration of a new tool but as an exemplar of a consumer or prosumer technology.

The diverse formal outcomes support the reiterated thesis that technology is now seamlessly insinuated into all areas of production and embedded into the material world that informs these artworks. It also has the useful outcome that these productions can also get on with the relatively unproblematised function of being cool ‘art objects’ that operate in the spaces of the white cube and the commercial gallery. Post-internet art is the first internet and computer-related practice to be supported by an international network of commercial galleries. This sets it apart not only from the work of earlier artists, but from other areas of cultural expression in the digital age. The internet has radically altered the economic exchanges that underpinned the operations of musicians and writers, who now find that their work no longer brings in money as it has become to all intents and purposes ‘free’ – as in beer but not speech, to borrow the programmers’ distinction. In comparison, in the experimental laboratory of contemporary art, post-internet practice seems to be successfully innovating ways to monetise and commoditise the digital realm.

It has become a given that digital platforms and exchanges represent not only new forms of economic activity and technology but also new constructions of individual and social identity, that they represent a rupture in human and social relations that is both essential and generational. The mission statement on the website for 89plus, an open-ended ‘multi-platform research project’ co-founded by Simon Castets and Hans Ulrich Obrist, reads: ‘1989 saw the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the start of the post-Cold War period, and the introduction of the world wide web and the beginning of the universal availability of the internet. Positing a relationship between these world-changing events and creative production at large, 89plus introduces the work of some of this generation’s most inspiring protagonists.’ Massimiliano Gioni, curator of the 2013 Venice Biennale, said in an article in the New Yorker last year that Trecartin’s 2007 video I-Be Area opened up a world he knew nothing about. ‘It was like a cultural watershed ... I felt this was the voice of a different age and a different time, a different sexuality, a different kind of behaviour. There’s this idea that a character can be many people at the same time. And the act of communication becomes the subject of his videos. We’re all trying to communicate, and what we communicate about is less and less relevant. When I watch his videos, I feel a speeded-up version of what we’re all doing.’

For the 2013 Venice Biennale, Trecartin, with regular collaborator Lizzie Fitch, combined different video works in a single installation. Although shot at different times, the shared locations and actors, and featured groups of young people, are shown partying and doing the sort of weird shit that young people have always done and which is now videoed and posted on social-media sites. Trecartin develops these actions to take on shifting properties, from engaging and cute to utterly feral, malicious and knowingly erotic. The footage is edited with a head-spinning energy and a knowing kinetic edge. In its native state – that is, the sort of footage that Trecartin’s footage draws on/echoes or maybe is to a degree – these images are not primarily intended to be screened in a public space with the Prada-hipsters of the international contemporary art world swishing by, but to be to be ‘shared’ with friends or peer-to-peer communities. In the commentary around the work, much significance is given to the posting of the footage on YouTube and Vimeo in addition to its incorporation into large sculptural installations. For Trecartin, this demonstrates that there is more than one way to approach and experience his practice. For the art market it also usefully signals that he is using contemporary platforms that supposedly exist outside the commercial gallery systems, reinforcing the work’s identity as an artefact of a new technology and a different culture.

In contrast, Ed Atkins’s installations focus on the individual. In the case of the vast multi-screen work Ribbons, 2014, exhibited at the Serpentine Gallery, it is an avatar of an individual called Dave. Dave is a computer-generated and 3D-modelled naked figure of a young man. We see Dave drinking, sitting at a table while stubbing out cigarettes in overflowing ashtrays, soliloquising in a woozy reflective stream-of-consciousness way and singing songs ranging from Henri Purcell to Randy Newman. Sometimes music in the background plays Richard and Linda Thompson’s Down where the Drunkards Roll. It is a sort of boho-garrett world: Dave is moody, getting drunk and smoking lots and he is sort of deep in a sort of incoherent way. At the end, Dave lays his head on the ash-stained table and his shiny skinhead cranium deflates as if this moody monologue has finally voided his brain. His is an enclosed, solipsistic universe and were it not digital, you feel that you might be able to smell the socks and the self-pity. Here, of course, lies the trick, the hinge around which the work rotates: all this subjectivity, all this searching, all this expression of self is a simulacrum, because Dave is an avatar – which, for some people, is very exciting.

The polymorphous perverse activities of Trecartin’s actors, and the angry and sensitive adolescent musings of Dave, echo previous representations of the young in both the 20th-century Avant Garde and in the wider culture. Trecartin’s gurning painted faces, and the intertwinings and enclosed exchanges, recall the films of Harmony Korine and Larry Clarke, Andy Warhol’s factory films, Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures and, more distantly, the airless incestuous eroticisms of Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye. Atkins draws on romantic iterations of doomed youth, the poète maudit, the eternally misunderstood, a dying digital Chatterton but with punk attitude. The earlier texts and films worked as bulletins from enclosed hermetic zones, from perverse identities, an underground of social, erotic, pharmaceutical and psychological actions enacted by those other than the bourgeois adult. Even in their representation they (seemingly) resisted or denied the mainstream gaze and operated as some sort of a reproach – for lost innocence, wildness, sexuality, freedom, impulsiveness, whatever – and as a threat and a challenge to the constructions and conventions of adulthood. These readings were animated by the ghosts of Henri Rousseau and his ‘noble savage’ and given charge by the investigations of Sigmund Freud and his constructions of the unconscious and the id.

Much post-internet practice draws on these tropes, and all of it is represented by the institutions as missives from a new experience and a somehow occluded or separate culture. But this is articulated at a time when all such activity is made immediately visible. A time when there is no underground, as the underground requires obscurity and secrecy. The internet means that contemporary identity, rather than having a social or political force, is increasingly an amalgam of data tags in a cybernetic relation with a public that constantly reaffirms them – the actions and their representations become the exchanges of atomised celebrity.

Demographic shifts following the postwar baby boom meant that youth cultures became significant forces in the West, first as models of identity, culture and social possibility, and latterly as markets and consumer groups. Now the West is witnessing another shift as the ageing baby-boomer generation comes to outnumber the young. The (new) young are increasingly excluded from political debate and the operations of capital. Youth unemployment in the West has soared since the financial crisis, access to money and property and education is increasingly rationed, and youth participation in traditional political mechanisms reduced. Public policy is directed to an affluent grey vote and shaped by the interests of corporations and a generation of the international rich who have expanded their wealth and power. These also constitute important consumers of contemporary art and their needs increasingly determine its operations.

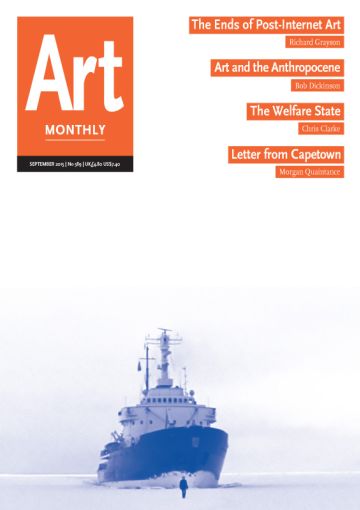

Despite this wide-spectrum erosion of political agency and economic marginalisation, ‘youth’ remains a valued commodity, certainly within the foundation myths of the baby-boomers. It is at this intersection of political powerlessness and psychic/social resonance that much of the post-internet work operates. It allows the expression of politics with little risk of those politics leaking into the material world. The people working in the start-up companies, designing the apps, generating content etc are young (even if their shareholders and financial backers are not), they are affluent and the arena in which they work is seen as the primary site for future economic expansion. Their values and attitudes become the gods and goddesses, the graces and virtues, of late capitalism. In turn, their temples host the new generations: Trecartin has blue-chip gallery representation and is showcased by billionaires’ initiatives such as the Zabludowicz collection (Lizzie Homersham, ‘Artists Must Eat’, AM384), 89plus boasts on its website that it ‘has developed a series of residencies with various partners internationally including the Park Avenue Armory in New York, the agnès b / Tara Oceans Polar Circle Expedition, and the Google Cultural Institute in Paris, which culminated in a one night exhibition at Fondation Cartier, Paris’.

Over the period of the emergence of post-internet art, the phrase ‘digital native’ has gained currency. First coined by Marc Prensky in 2001 it denominates a person who, since gaining awareness, has known no other world than that which is digital and networked. This is in contrast to a ‘digital settler’, a person who grew up in the analogue world but who has driven developments in the digital sphere, and the ‘digital immigrant’, someone who may use email or social networks but remains insecure and foreign in these strange new lands. The branding of post-internet art allows the commodification of the actions of digital natives for a market currently composed mostly of settlers or migrants. Given the inevitable fact that the non-natives are going to die sooner than the rest, this is perhaps the last moment when such a neat generational divide, with all its exciting romantic resonances, can be constructed in the art marketplace.

No matter what else the post-internet movement may be doing, it is working to enhance the brand that contemporary art and its institutions, post 1989, assiduously cultivate; it allows the art world to act out the rhetoric of an Avant Garde at a time in which no Avant Garde can operate; it allows earlier models of youth, of rebellion, alternative cultures, otherness, innovation, on-the edgeness, cutting-edgeness, modernity and revolution to be relaunched and rearticulated and rebranded and resold through the prism of the operations of the digital universes. And in doing so it seems to be following the strange logics of commodification that are at play in the digital economy.

The post-internet art arena becomes a place where these ideas are represented and aestheticised as affectless signifiers, as representations of themselves and as weightless commodities.

Richard Grayson is an artist and curator based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 389: September 2015.