Feature

Art/Class

Bob Dickinson wonders whether working-class culture can survive in the UK

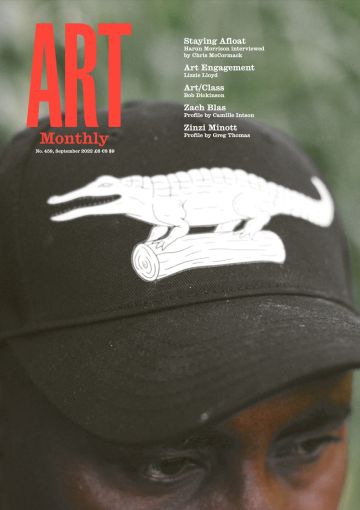

Oona Doherty, Hard to be Soft – A Belfast Prayer, 2017

Since the Thatcher years there has been a long-term grinding down of one particular sector of UK society: its working class. Analysing the class-based nature of the UK is always subject to debate, but in 2011 the Universities of Manchester and York collaborated with the London School of Economics (LSE) on the Great British Class Survey, which redefined those who survive on the lowest income. The grouping was divided into three descending levels: the Traditional Working Class, the Emerging Service Sector and the Precariat. Together, they made up 48% of the population.

Many among this 48% have already been punished by deindustrialisation, dependence on the gig economy, and the impact of the worldwide financial crisis of 2007/08. Now they face another financial crisis, partly a result of fuel price increases and the war in Ukraine but also the result in large part of UK government policy. Poverty is rising: the independent think-tank the Resolution Foundation, which focuses on improving living standards for those on low to middle incomes, reports that despite poverty having fallen in relative terms during the pandemic (when most people became poorer), the number of those in absolute poverty in the UK will rise by 1.3 million in 2022/23. This growing inequality is a direct result of the austerity policies of successive Conservative governments, accelerated under the Boris Johnson administration by the deliberate neglect of public services and increased privatisation, notably of the NHS, and the squeezing of benefits. As if this was not bad enough, then came the return of inflation and a cost-of-living crisis exacerbated by Brexit, and the irresponsible and duplicitous handling of negotiations with the EU by the departing prime minister. All of these factors have contributed to a perfect storm of bad news for Britain’s poorest, taking its toll on mental as well as physical health.

But how seriously does the art world take this assault on almost half the population? Not very, it seems: talking, for instance, about social inequality in the context of art galleries and museums can be a maddening exercise. As the paper The Art World’s Response to Inequality, published by the LSE in 2020, observed, ‘strategies around diversity and inclusion in the cultural sector risk being largely delinked from their intersections with material marginalisation, thus running the risk of disconnecting issues of representation from wider struggles around production and social and distributive justice’. One of the reasons for this was summed up in terms of ‘the worrying concern that addressing economic inequality directly might be problematic because it could affect funding and patronage’.

Things might be different if it was easier for young people from working-class backgrounds to obtain a foothold in the art world. An earlier report, Panic! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries, 2018, by academics from the universities of Edinburgh and Sheffield, revealed that only 18.2% of those employed in music, performance and the visual arts came from working-class backgrounds. In 2021, education secretary Gavin Williamson’s reply to this imbalance in England, was, however, to halve the funding for arts courses across higher education, instead prioritising science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) courses. Announcing recent cuts of £72m to arts funding in London (Artnotes AM455), to be redistributed elsewhere around the country, culture secretary Nadine Dorries argued that it would add to the government’s much-vaunted ‘Levelling Up’ programme. If anything, the redistributive effect will add little nationally, but will have a serious impact on economically deprived parts of the capital (the first tranche of Levelling Up funding went disproportionally to Conservative-controlled councils, including Dorries’s own constituency, which is among the most affluent in the country – Artnotes AM455). In times of culture wars, it seems the arts are fair game for a government desperate to score points, especially when it comes to class. Witness recent ‘champagne socialist’ sneers in Parliament by Conservative deputy Dominic Raab directed at Labour’s deputy leader Angela Rayner (who hails from a working-class background in Manchester) after she was seen attending an opera at Glyndebourne. These days, if you are working class, you might not be blamed for wondering if it is even allowable to look at art, let alone think of becoming an artist.

Somehow, some art does emerge that both reflects and engages with these increasing levels of inequality. In this country, where many formerly strong, working-class communities have gone into decline, despite the very workplaces that neighbourhoods were built around having long been closed down or in need of drastic repair, working-class speech and imagination still survives and evolves. Pop culture makes easy profits from this, but it is less easy to convert this vibrant culture into visual art. Michael Dean’s work, however, is full of this sense of language. His collapsed, playful and highly rhythmic sculptural explorations develop from written notes that then take on lives of their own, the lettering and glyphs evolving distortedly into solid objects, sometimes tied up or trailing hazard warning tape. Much attention was directed towards this Newcastle-born artist’s Turner Prize-nominated work from 2016, United Kingdom poverty line for two adults and two children: twenty thousand four hundred and thirty six pounds sterling as published on 1st September 2016, primarily because of its huge pile of pennies – one of which was removed by Dean, putting the cash below the government’s stated UK poverty line for that year. Lurking in the background, however, there were those strange, funny, worrying figures and the relationships they had with one another – and us. More recent works, such as Your Text Here, 2020, feature groups of these forms seemingly caught on the verge of moving about, embracing, hanging around in corners, or distorted LOL emoji faces, lined up, deteriorating, taped and piled up, one on top of another, or folded, as in A Thestory of Luneliness for Fuck Sake, 2021. That Dean’s sculptures are usually conceived and presented as immersive situations reflects the artist’s interest in involving the viewer, sharing that language and creating a means for us to take part in an inventive linguistic process. Speech, slang, an awareness and internalisation of the impact of social media, and of speech as a kind of performance, or speech-act, may seem to be taking us into the worlds of Jacques Derrida or JL Austin, yet we remain in the realm of working-class experience, not least because there is a rare restlessness and anger here. We do not encounter such seething anger in other recent artworks highlighting labour, for example Suzanne Lacy’s otherwise very worthy recent UK projects The Circle and the Square, 2015–17, in which she produced a film and music project with local communities, musicians, and religious groups in a multi-ethnic, former mill town in Pendle, Lancashire, and Uncertain Futures and Cleaning Conditions, 2021, where volunteers from labour, living wage and immigration organisations swept the floors of Manchester Art Gallery in a homage to Allan Kaprow. While these interventions poeticised authentic working-class life and feeling rather than directly reflecting it, they did succeed in challenging the commonly held misconception of a working class that is predominantly white. Of all the social classes, today’s working class is in fact the most ethnically diverse by far.

The diminishing resources, emotional as well as economic, that remain available to poorer and marginalised people have, in the UK’s recent past, been witnessed by photographers such as Paul Graham in his series ‘The Great North Road’, 1981–82, and ‘Beyond Caring’, 1984–85, the latter especially telling in its detailing of facial expressions and slumped bodies, timelessly stuck in unemployment benefit office waiting rooms. Recording deprivation on a personal level is an even more uncomfortable experience, especially through the lens of a photographer such as Richard Billingham, who focused on his own family, including an alcoholic father and a violent mother, crammed into a tower block in Cradley Heath near Birmingham, in his series ‘Ray’s A Laugh’, 1996, and in the film Ray and Liz, 2018, in which he recreated episodes from his childhood.

Most recently, continuing distress and desperation have been observed outside the big cities. In the Conservative-controlled area of Breckland, Norfolk, the town of Dereham may appear to visitors who pass through it as a traditional English market town, picturesque and comfortably off. The locally based photographer and home carer JA Mortram tells a very different story, however. His searing series of black-and-white photo portraits, ‘Small Town Inertia’, 2013–22, concentrates on people struggling to survive against a rising tide of poverty and recent cuts to local services. The titles of his photographs read like frontline reports from the chaotic historical period we are still enduring: James watching a Brexit debate on the news, for instance, or Cathleen, after an eight-month battle to appeal her P.I.P., bedridden, she endures another grand-mal seizure. Most of Mortram’s photographs evoke a sense of unease and precarity. In one, an elderly blind man called David, wearing a coat and fur hat, is seen trying to keep warm with a cheap electric heater in a murky room piled high with clothing. In another, a woman watches TV while her shirtless partner wrestles with a pet dog on the settee, the floor below them covered in refuse. Dogs, settees and television sets feature in many shots, nearly all interiors, but the eyes we see are too often staring into the thousand-yard distance. Many of the portraits Mortram has produced are part of longer sequences, reflecting the relationships the photographer establishes with his subjects. One notable series, taken between 2014 and 2016, features a man known as Tilney1. Suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, and living alone, Tilney1 neglects to take his medication, but works obsessively on journals and collages. Meanwhile, cuts to medical services mean that he no longer receives visits from community psychiatric nurses. Increasingly isolated and prone to obsessive thoughts, Tilney1 continues to show flashes of lucidity. One photograph of him looking at a TV screen is captioned, ‘Though the news is often of great stress, Tilney1 pays particular attention to the Labour leadership election’.

Mortram becomes increasingly helpless, though, and as a result, he comments, ‘I can do nothing but witness,’ adding, ‘it was watching a plane fall from the sky, aflame.’ Eventually, Tilney1 is taken to an acute admissions ward within a psychiatric hospital in Norwich. Following his release he is terrified: his medication has been altered. He recovers, but again forgets his meds, and is readmitted, this time to a private hospital. This photographic sequence witnesses him slowly sinking, entirely because of cutbacks to the health system.

Another insight into life in the rural and semi-rural world, entirely different from that of Mortram, is seen in the recent work of Madinah Farhannah Thompson. Like Mortram, she grew up in Norfolk, but she was one of the only black children in her primary school in Norwich and experienced a profound sense of exclusion. Her experience of isolation and mental illness is repeatedly explored in her current work through performance, writing and film. Here, a black, female body is centrally placed in a landscape that appears tranquil but which can turn hostile. In one piece, The Black Flaneur Part 3: Being Black Outdoor/s (inside/outside and nature), 2021, she writes: ‘Now each time I go to the supermarket or for a walk, I return full of anger … Seeing “all lives matter” tagged on bollards near my house reminds me that it is more than mere discomfort that causes this feeling: it is fear.’ In other works, we encounter a body in recovery and reflection, positions of calm and strength. Sea Salt and Spell, 2020, for instance, features Thompson seated on a floor onto which a projection shows her in a bath with the water draining away, revealing rocks she collected from the Norfolk coast and kept at home. Thompson says about this that she was ‘creating a spell by calling up a memory’ – and the words of her accompanying poem speak volumes: ‘I feel closest to Allah when I am at the sea / I feel closest to myself when I am in the sea / I feel closest to my mother when I am away from her / I wanted to be weighed down by these rocks / Now I know they hold me fast unto myself.’

These studied approaches by Thompson and Mortram to the subject of isolation appear different, but they share a central concern with the body. While Mortram’s work reminds us that what his subjects are doing or going through is clearly not a performance, Thompson’s performances are autobiographical and reflective, and therefore also portraits of identity. The thought-through anger of Thompson and the empathetic anger the viewer feels at Mortram’s images even bring to mind the early work of Stuart Brisley, including And for today … nothing, 1972, and Beneath Dignity, 1977, because of their concentration on the overwhelmed body – the latter work, notably, is also a comment on the working lives of coal miners. Both these works were preceded by one that took its title from Brisley’s National Insurance number, ZL656395C, 1972, in which the artist lived for several days in the temporary space of the Gallery House in London, eventually demolishing a wall separating him from spectators, because – at that point – he considered the work to have been a failure. This notion of failure, with its attendant bodily responses of anger, violence and possible self-destructiveness, reflected the artist’s increasing frustration at the perceived failures of the revolutionary counterculture, an internalisation of the violence used against the under-represented.

Starting in the 1980s, however, the unionised working class had to internalise another kind of violence – the violence of Margaret Thatcher’s government in destabilising and destroying working-class organisations. For some on the left, the assault on unions in the UK is seen as the whole point of neoliberalism: the removal of the labour movement’s ability to defend itself. Everything that followed, including globalisation, free markets and the massive stashing of funds in offshore tax havens, happened because the unions were stymied. For workers on or under the ground, however, it meant widespread, long-term joblessness as the hardest and most traditional industries such as shipbuilding, steel making and coal mining closed down and, in the case of this last trade, its pride and sense of identity was painfully destroyed by the miners’ strike of 1984–85. When thinking about this history in relation to contemporary art in the UK I remain unsure about Jeremy Deller’s Battle of Orgreave, 2001, and book The English Civil War Part II, 2002. The restaged, performative battle, filmed by Mike Figgis, referred to the 1984 conflict between striking members of the National Union of Mineworkers picketing a coking plant in South Yorkshire and ranks of police on foot and on horseback. Any comparison with the wars between king and Parliament in the 1640s is misleading, because the miners owed their radical potential less to Roundheads or Levellers than to the industrial revolution from which the English working class emerged in the 18th century. The social divisions that the strike and this particular conflict gave rise to – in the media and in society more widely – were further inflamed by Orgreave, and by Thatcher’s notorious description of the NUM as an ‘enemy within’. The miners’ own divisions – recently riffed on in the BBC television series Sherwood – were a tragic reflection of the government’s efforts to split the workforce by reassuring the breakaway, strike-breaking Union of Democratic Mineworkers that its members would receive preferential treatment. Despite this, the miners’ strike forged important alliances between other groups also resisting oppression from police and government, notably Lesbian and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM); their campaign, focusing on South Wales mining areas, received the headline ‘Perverts support the Pits’ in the Sun newspaper at the time, but was later celebrated in the successful feature film Pride, 2014.

The effects of unemployment on youth during this period and after, together with the racist stop-and-search practices of the police, have repeatedly contributed to outbreaks of rioting across the UK ever since. In Northern Ireland, however, things were very different. While sectarian violence may have more or less ceased with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 (although the current Tory government is toying with undermining it by triggering Article 16 of the Northern Ireland Protocol for the sake of Brexit, stoking a row with the EU which could easily reignite sectarianism), in this post-conflict society, internalised violence continues to run deep beneath the surface, gnawing away inside many individuals. Higher rates of mental illness than the rest of the UK, higher use of antidepressants and a higher incidence of self-harm are devastatingly coupled with the lowest proportion of funding for mental health in the UK. Statistical research by the Northern Ireland Assembly notes the impact of the recession, unemployment, the legacy of the conflict and rising drug and alcohol use on suicide rates in the province, which increased by 43% among women and 63% among men between 2000 and 2018. The report noted that while women ‘were more likely to self-harm and to attempt suicide, men are three times more likely to die by suicide’, pointing toward the ‘stigma’ of discussing mental health combined with access to ‘more lethal methods of suicide’. The report also highlights a number of high-risk groups, which includes gay, transgender, ethnic minorities, farmers, unemployed, rurally isolated, divorced or separated males. It is a picture of an unfolding tragedy affecting an already damaged society.

In response to this information and, in particular, the way that suicide afflicts young men in the province, the Belfast-born contemporary dancer Oonah Doherty built a performance, Hope Hunter and the Ascension into Lazarus, 2015–, which has been presented as street theatre as well as put on in prisons and youth detention centres, and is included in this year’s British Art Show. Doherty as the Hope Hunter uses dance to investigate what she refers to as ‘the rhythm that the boys give off in the street’, twisting her face as well as her body to mimic all the banter, cat-calling, crotch-grabbing and pent-up anger of disaffected working-class young men. Her movements respond to background audio clips of youths arguing, fighting, bragging and crying, intermixed with the rising, plaintive choral harmonies of Gregorio Allegri’s Miserere. Elements from this work have made their way into a bigger, four-part performance, Hard to be Soft – A Belfast Prayer, which Doherty describes as a ‘sort of sci-fi stages of the Cross’. Enclosed in a giant cage-like set, it features a ten-strong dance group called the Sugar Army, consisting of locally recruited girls, trained by Doherty not just in dance but also in awareness of the way young females are portrayed in the media. It is angry, but also an assertive and joyful approach to working-class culture in almost impossible times.

The continuing assault on the working class, on the poor and the excluded, is not just a story of stalled pay increases, job losses, education gaps, lack of opportunities, privatisation and underinvestment in the NHS, the long-term results of deindustrialisation and the imposition of what Charles Dickens – someone who grew up poor – might have called ‘Low Expectations’. It is also a consequence of a Conservative Party desperate to stay in power whatever the cost to society. The present government’s arrogance, vacuity and lack of ideas only make a widespread disillusionment with all politicians of every hue so much deeper. Art can capture some of the complexity of what Britain has become, but making politics really work for all is a tough call. Artists take note.

Bob Dickinson is a freelance writer based in Manchester.

First published in Art Monthly 459: September 2022.