Review

Alex Margo Arden and Caspar Heinemann: The farmyard …

Larne Abse Gogarty finds this exhibition and two-act play to be an antidote to today’s cruel and crass political landscape.

Alex Margo Arden and Caspar Heinemann, The farmyard is not a violent place and I look exactly like Judy Garland, performance

I went to see ‘The farmyard is not a violent place and I look exactly like Judy Garland’, an exhibition and two-act play staged by Alex Margo Arden and Caspar Heinemann at Cell Projects Space, shortly before the general election. Upon leaving, feeling uplifted, I thought about the play as an antidote to a cruel and crass political landscape, in its anti-work sentiment, humour and elaborate, luxuriant investment in making as a utopian project. I mean antidote here less as a cure and more as a potion, tincture or salve that might protect or offer a spell for negotiating the world differently, because neither Arden and Heinemann’s play, nor the accompanying exhibition, is reparative or ameliorative. As Heinemann’s character states: ‘Healing is dangerous.’

The title of the play and exhibition nods to gay icon Judy Garland, whose song ‘Howdy Neighbour!’ from Summer Stock, 1950, forms a refrain sung by Arden and Heinemann. Summer Stock features Garland as a farm owner whose sister turns up with a theatre troupe that proceeds to rehearse in the farmyard’s barn with the farm as the setting, and this mise en abyme structure is repeated in Arden and Heinemann’s play. Their story begins with their escape from the somewhat enigmatic ‘Farmyard’. A clear picture of life there is never established, but as the play unfolds we learn that it might have been something like a cult, one where the characters were compelled to build ‘mysterious purposeless objects for mysterious unknown powers’.

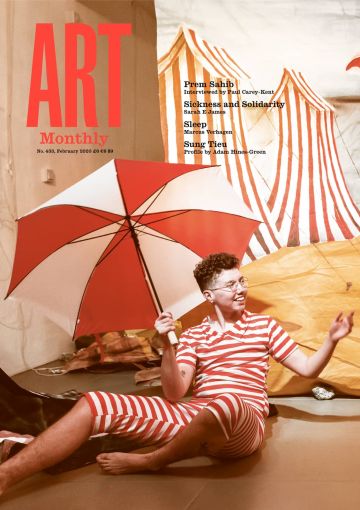

Arden and Heinemann’s voices are presented in the play through a recording, which they mostly mime along to, occasionally breaking into song. The device of working with a recorded rather than spoken voice connects with the somewhat dissociative multiplication of selves during the play. Arden’s character doesn’t realise she shares the same injury as Heinemann until he points it out; and a scene set inside the body of the whale results in the characters multiplying until they can’t find the ‘real’ version of each other. This disassembling is exaggerated through numerous costume changes. Beginning with an elaborate red and white costume, bunched, bustled and tied like a heavily layered kimono topped off with mushroom headgear, Arden and Heinemann also dress as ancient Romans and Victorian schoolchildren, hobbits and horses, with the most affecting costume being their transformation into elderly people, wearing masks and hobbling on walking sticks. The costumes were matched by painted canvas screens, forming an inspired economy of means to establish set changes, with each being clipped onto a system of hooks and pulleys, and raised like flags. The sets included a view of London with Tower Bridge and the Thames, to ancient ruins, woods, barnyards, sand dunes and caves. In the moment where the characters arrive in London, the mood is of queer escape to the city, yet this exceeds any clichés about self-realisation. Instead, the city proves impossible, with Heinemann’s character pronouncing, ‘I never wanted to go to the city to begin with’.

Both Arden and Heinemann are trans, and themes of gender and queerness run through this project, but in a manner distinct from the affiliation with fashion and lifestyle present in much contemporary queer art, from boychild to Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz to Sophia Al Maria. In distinction from those practices, the play does not present an affirmative vision of a specialised, individual self arrived at through the Farmyard escapee’s quest. Instead, themes of identity and embodiment are teased out in fundamentally relational, but also occluded, strange and pessimistic ways, as alluded to in the idea that ‘healing is dangerous’, part of a line which concludes with a question: ‘Remember everything that happened?’

Visiting the exhibition allowed for a better look at the scrawled words covering parts of Arden and Heinemann’s costumes seen from a distance during the play. Two sand-coloured aprons are pinned to the wall, covered with platitudinous statements, somewhere between gap-year traveller memories and a leaving card for a colleague: ‘You are about to embark on a journey that will bring you fond memories and a different view of the world. Make the most of it and be safe!’ Similar statements cover the hefty canvas bags storing all their costumes, exhibited in the upstairs gallery, placed adjacent to a sculpture that forms the seating for the audience. Composed by luggage, chairs, a chaise longue and haybales chained together, this work is formally akin to the sculpture sited at the rear of the gallery. Entitled Changing the face can change nothing, but facing the change can change everything, here we find a large pile-up of furniture, mirrors, ladders and luggage which, like the seating, transforms domestic objects into assemblages of fantasy and play. Set alongside the stunted, eschatological narrative of the play, this aspect of Arden and Heinemann’s work inherits Paul Thek’s processional approach to objects.

Aside from the cascade of mobile phones that spill out from a backpack during one point in the play, Arden and Heinemann’s work is resolutely pre-digital. The costumes, furniture and songs all reference various points in the past, from ancient Rome to the 1950s. Yet the work doesn’t lapse into a retro or nostalgic mood. Rather, the past is presented to emphasise Arden and Heinemann’s characters as forever marked by the Farmyard as much as they try to assimilate into the world outside, and as necessarily sticking with their belief that ‘forgetting is dangerous’. At the end of the play, they give up on what seems to be an increasingly obscure mission, deciding instead to turn their attention to the multiple objects now littering the stage. In turn, each of them joyfully pronounces that they could ‘use this and this to make something out of this and this’. Making, like the sentiments captured in Howdy Neighbour, becomes the possibility of abundance, the promise of a ‘happy harvest’ with no ‘mortgages or loans’, and a means to access an unmediated, Cockaigne-like land, where they might, as Arden’s character announces, ‘close the hole between inside and outside, and I don’t think just in ourselves’.

Alex Margo Arden and Caspar Heinemann’s ‘The farmyard is not a violent place and I look exactly like Judy Garland’ took place at Cell Project Space, London, 28 November 2019 to 26 January 2020.

Larne Abse Gogarty is a writer and lecturer in history and theory of art at the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL.

First published in Art Monthly 433: February 2020.