Viewpoint

An Alternative History of Art

Eddie Chambers argues that this BBC Radio 4 series continues the UK’s marginalisation of major 20th-century African-American artists

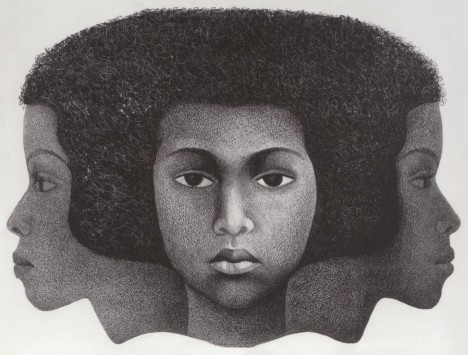

Elizabeth Catlett, Which Way, 1975

As I write this, Radio 4 is running a series it describes as ‘An Alternative History of Art’. Across ten 15-minute episodes, the series looks to rescue from obscurity artists somewhat forgotten or overlooked by history, thereby creating an alternative history. The artists, Eileen Agar, Elizabeth Catlett, Karl-Heinz Ader, Marwan, Jim Nutt, Dorothy Iannone, Ibrahim El-Salahi, Helen Chadwick, Benjamin Patterson and Rotimi Fani-Kayode, are each given encapsulated documentaries presented by either Whitechapel Gallery director Iwona Blazwick, Serpentine Galleries artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist or Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art’s curator Naomi Beckwith. When the series was trailed, I speculated that one of Beckwith’s ‘forgotten’ black artists would likely be a figure such as Jacob Lawrence or Charles White: monumental and canonical figures of African-American/American art of the 20th century, relatively well attended to in catalogues and monographs and (stateside at least) in major exhibitions who would, when presented to Radio 4 audiences, be recast as practitioners momentarily rescued from obscurity by the good graces of the BBC, before being summarily returned to the art-historically marginal spaces from whence they came.

What transpired was as bad as I had feared, with the African-American artist showcased during the first week of broadcasts being no less a figure than Catlett. It is difficult to overstate just how canonical a figure Catlett is in narratives of American art of the 20th century. Her signature body of work – a set of linocuts executed in the 1940s, I am the Negro Woman (renamed I am the Black Woman in the late 1980s to reflect long-since changed nomenclature) – established her as one of the most eloquent artists whose work unfailing came down on the side of the oppressed and the excluded. Yet here she was being trailed as an artist who had ‘received little attention from the mainstream artistic canon and from international institutions’.

The major problems with reframing Catlett as an overlooked and forgotten figure of art history are these: firstly, she lived to be nearly 100, dying just recently in 2012 having dedicated her life to art and producing what was, by anyone’s standards, a monumental body of appreciated and valued work. Secondly, and perhaps more troublingly, the inclusion of Catlett in the Radio 4 series was fundamentally disingenuous because it conveniently overlooked the reasons why, within the UK and among certain people, Catlett is not well known. In short, it is the UK art world’s reluctance to take seriously African-American artists as individual practitioners of merit that has led to disfigured spaces being opened up into which supposedly alternative histories can be benevolently inserted, albeit fleetingly, squeezed between more substantial offerings in Radio 4’s weekday morning schedules.

The reason Catlett and other major practitioners, such as Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence and Charles White, are routinely disrespected by the UK’s major art institutions is because of an enduring pathology that dictates that artists such as these can and must only show up in catch-all exhibitions with grand and comprehensive historical arcs. In recent decades, such exhibitions have included ‘Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance’ at the Hayward Gallery and ‘Black to Black’ at the Whitechapel Gallery. These undertakings showcased approximately 30 and 50 artists respectively. Though not all practitioners were African-American (the latter show in particular drew in artists from the Caribbean and the UK), these excursions effectively operated as black shows within otherwise largely white gallery programmes. Most recently, we have had ‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power’ at Tate Modern (see Richard Hylton’s feature ‘Black Art UK/US’, AM410). Again, this exhibition featured a grand historical arc and, again, it showed more artists than can be named without recourse to its catalogue. Catlett was included in both the Whitechapel and the Tate Modern exhibitions, but the impact of individual artists’ work is perhaps diminished in such crowded environments. The most troubling aspect of these filled-to-capacity, catch-all mega exhibitions is that they take place in galleries whose programmes are otherwise largely characterised by respectful attention given to individual (white) practitioners. Such skewed curatorial approaches bolster the view that certain artists can exist as serious and credible practitioners of note and merit, while certain other types of artist can be assigned only the most fleeting attention, in large and cumbersome group exhibitions, their peripheral status underlined by them popping up in a programme such as ‘An Alternative History of Art’.

The gravity of the situation is underlined by the fact that there has never – as in never ever, not once – been a major substantial, stand-alone exhibition in the UK by any of the most important and prolific African-American artists of the mid 20th-century, such as those mentioned earlier: Bearden, Lawrence, White and, of course, Catlett. To these names can be added those of artists such as Sam Gilliam, Faith Ringgold, Betye Saar etc. While practitioners such as these are arguably established as canonical figures in the US, with accompanying curatorial excursions, at least every now and then, in the UK they are treated as little more than generic exhibition fodder, with one or two of their number considered as candidates for ‘An Alternative History of Art’. What is it that prevents the UK art world from presenting solo exhibitions by black practitioners whose historical importance, singular contributions and individual artistic dedication are beyond dispute? Questions such as these are masked by seemingly benevolent gestures, for example of a figure like Catlett being given, quite literally, her Warholian 15 minutes of (UK) fame.

Catlett does not belong in any sort of alternative history. She may have regarded the art establishment with a certain ambivalence, but she had extraordinarily good reasons for doing so, beginning, perhaps, with her efforts to gain admission to art school as a young woman. She was denied entrance to the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh – now Carnegie Mellon University – solely on account of her race. We must not lose sight of the fact, though, that many scholars and curators have undertaken hugely important work over many decades to ensure that Catlett is now regarded as being as important an American artist as any other (in this regard, Samella Lewis’s masterful monograph of 1984 is unsurpassed). We might also care to consider that Catlett’s work graced the cover of the November 2017 issue of Artforum.

Rather than creating liberal-minded alternative histories, the art establishment and its mouthpieces would be better off reflecting on why it is that certain artists are routinely sidelined, as if decreed by the forces of the universe, rather than the pathologised and prejudiced inclinations of people perhaps most politely described as cultural supremacists.

The ten episodes of ‘An Alternative History of Art’ were broadcast on BBC Radio 4, 5-17 March 2018.

Eddie Chambers is a professor in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Texas, Austin.

First published in Art Monthly 415: April 2018.