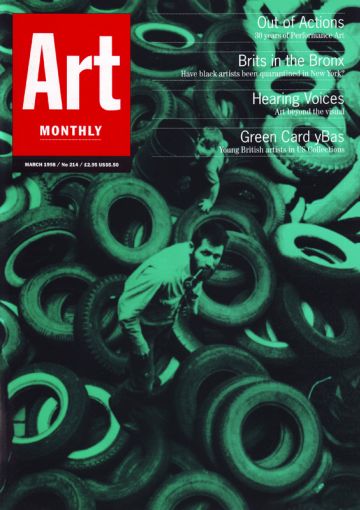

Feature

Brits in the Bronx

Has black art from Britain been quarantined in New York asks Eddie Chambers

‘Transforming the Crown’ is an exhibition that throws up many, many questions. Why these artists? Why this selection of work? Why these venues? Why at this moment in time? And why this exhibition title? Of course, questions such as these could be applied to almost any group exhibition but, in the case of ‘Transforming the Crown’, answers to these questions are vague, unsatisfactory or entirely speculative.

In recent years New York galleries have been playing host to exhibitions of work by artists representing the new generation of so-called young British artists (yBas). It may be tempting to view ‘Transforming the Crown’ as an extension of this or as a widening of the parameters that Americans have been encouraged to see as defining ‘British’ art. But within the exhibition brochure, Mora J Beauchamp-Bryd, the show’s curator, makes no reference whatsoever to the wider artistic context in which black artists in Britain operate. Consequently, few gallery visitors are in a position to establish a proximity between these British artists and their white counterparts.

There are depressingly familiar ways – inadvertent or otherwise – in which ‘Transforming the Crown’ has been located. The main sites of the exhibition are the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Bronx Museum. (The third site is the much smaller venue, the Caribbean Cultural Center, which was the working base of the exhibition’s curator.) In New York, these spaces are all widely perceived as primarily existing to service black and other non- white communities. This policy of ‘black artists’ work for black audiences’ leaves downtown and midtown galleries, as well as the heavyweights such as the Museum of Modern Art, free to get on with the business of showing art and servicing audiences that lie geographically and artistically beyond the ethnic quarantine. We do not know if the major art spaces of lower Manhattan responded negatively to approaches to take ‘Transforming the Crown’; neither do we know if the Studio Museum and Bronx Museum were deliberately and positively chosen. But when it comes to exhibiting the work of black artists, these are vitally important questions that ought to be acknowledged as such. Within her introduction, Beauchamp-Bryd shirks them completely.

And what does ‘Transforming the Crown’ actually mean? If it is meant to suggest that African, Asian and Caribbean communities are ‘reinventing’ or ‘transforming’ Britain and assorted manifestations of ‘British’ culture and identity, then Beauchamp-Bryd declines to provide us with chapter and verse citations and examples. The absence of this desperately required hard evidence and substance leaves us with an ultimately meaningless exhibition title that mocks much of the reality of black Britain’s individual and collective historical and contemporary experiences.

For African, Asian and Caribbean artists in Britain, what was significant about 1966 or, for that matter, what was significant about 1996?* In answer to both of these questions, we can each think of something or we can think of nothing. 1966, England hosting and winning the World Cup? 1996, the deaths of Ella Fitzgerald and Tupac Shakur? After due consideration, my favourite answers are that in September of 1966 I had my sixth birthday and in October of 1996 my Frank Bowling exhibition opened at its first venue. But (notwithstanding the monumental importance of both these events) the years in question are supposed to have a greater significance because they mark the three decade period mapped out by the exhibition. Beauchamp-Bryd describes the decades in question as ‘a critical thirty-year period’ but adds nothing further to justify or explain this claim. In this sense, the exhibition promises a level of curatorial and art historical rigour that it manifestly fails to deliver.

Beauchamp-Bryd has spent much of the past several years toing and froing across the Atlantic, working on the exhibition in fits and starts. Her aim was to introduce to New York audiences a major, wide-ranging look at the diversity, history and strength of visual arts practice amongst Britain’s black artists. Beauchamp-Bryd was of the opinion that such an ambition was best served by shipping in the biggest trundling roadshow exhibition that she could create. In Beauchamp-Bryd’s quest, no stone was left unturned, no artist was to be left unconsidered. Despite the obvious flaws in such a strategy, Beauchamp-Bryd had decided that ‘Transforming the Crown’ was to be a fulsome, definitive introduction.

Unfortunately, the eventual exhibition falls rather short of this mark. Certainly the exhibition contains work by a lot of artists – 58 in total, who, in turn, are responsible for nearly 130 pieces. But this is such a shambolic, incoherent, unfocused and piecemeal selection as to render irrelevant the notion that the exhibition has been in any sense of the word curated. The trouble with this exhibition is that those of us with any sort of familiarity with this work and these artists instinctively look for the most obvious gaps and omissions. Within ‘Transforming the Crown’ these gaps and omissions exist in abundance. How can there be a 30-year survey of black artists in Britain that omits Rasheed Araeen? It is true that the man can be hard work, but an exhibition such as this that fails to invite him on board marginalises itself. And what about Donald Rodney, surely one of the most interesting artists of his generation? Saleem Arif was not there either; nor was there anything by Tarn Joseph or Frank Bowling. Can you believe that?

While there were a number of other glaring omissions, my purpose in highlighting them is to do more than flag up curatorial blunders. After all, gallery-going audiences might not even be aware of some of these gaps. However, I believe that New York audiences have a right to have it explained to them in the clearest language why this 1966-96 period was settled on, why certain artists have been included and why certain artists have been excluded. The absence of such critical information in the exhibition brochure renders the entire exhibition suspect and evasive.

As for the work itself, what an odd assortment it is. There are very few key works in the exhibition, though Sonia Boyce’s Some English Rose is present. So too is one of Faisal Abdu’Allah’s magnificent and fascinating re-renderings of The Last Supper. Much of the rest is reminiscent of unwanted leftovers, out-takes or remaindered bookshops at their worst. Gavin Jantjes, one of the most exciting additions to the British art community of the 1970s, is represented by two smaller works that somehow managed to take on a slight and apologetic air. Even Sun, Sea and Sand, the contribution by Yinka Shonibare, one of London’s most intelligent and provocative artists, appears in this exhibition as a dull, lifeless and dusty work. This aura of apology pervades many of the works in this exhibition. lt is dispiriting to see so many artists represented by minor and less significant work.

Regrettably, though several months have elapsed since the shows opened, the exhibition catalogue is still not yet published. (Though some texts from the catalogue are in circulation.) This means that we are not yet able properly to avail ourselves of Beauchamp-Bryd’s arguments and opinions about the work of black British artists. I always have problems with ‘international’ exhibitions in which the voices, visions and agendas of the curated are absent from the structure and framing of the exhibitions in question. ‘Transforming the Crown’ is just such an undertaking. The flip side of this is that the major voices and expressions that are officially attached to the exhibition are those of individuals who have no direct contact with Britain or its communities of black artists. This disconnection inevitably results in a number of catalogue texts that barely rises above the superficial and at times descends to the erroneous. Instead of statements and texts directly provided by the exhibitors themselves, we have essays like ‘A Question of Place: Revisions, Reassessments, Diaspora’, a worthy-sounding catalogue text supplied by Okwui Enwezor in which we read ‘The African artist upon arrival in Britain encounters an untrusting and alienating social environment. lt could begin at the very moment of disembarkation, either on the docks of Wolverhampton … ’. Having been born and brought up in Wolverhampton, I can assure Enwezor that Wolverhampton, being landlocked for miles around, has no docks, just canals. It would take more than a pioneering or migratory spirit to disembark there.

In viewing this exhibition, I was obliged to ponder on the question of why artists would ever want to attach themselves to such a shoddy undertaking. But, as Richard Hylton pointed out in a previous issue of Art Monthly (AM211), it is not as if artists themselves are press-ganged into these dodgy exhibitions. Or maybe they are.

Much of the press response to ‘Transforming the Crown’ is polite and enthusiastic. For example, an end-of-January listing of the exhibition in the New York Times described it as being ‘packed with terrific artists ... projecting a unified force field of energy as palpable as it is hard to define’. It must be left to others – not least the exhibition reviewers themselves – to fathom how much of this praise is genuine art appreciation and how much is derived from a sense of liberal surprise that not everyone in Britain is white and speaks with a plummy accent.

*‘Transforming the Crown: African, Asian and Caribbean Artists in Britain, 1966-1996’ is at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, the Studio Museum, Harlem and the Caribbean Cultural Center, New York to March 15 1998.

Eddie Chambers is a freelance curator.

First published in Art Monthly 214: March 1998.