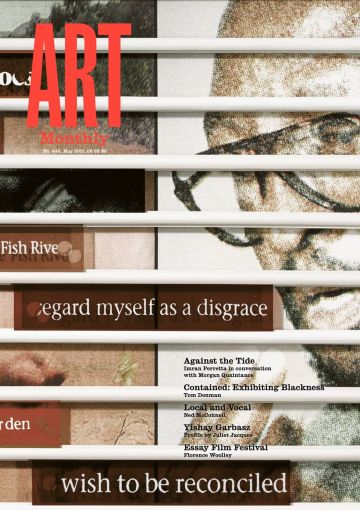

Feature

Contained: Exhibiting Blackness

Tom Denman argues that Tate used its Lynette Yiadom-Boakye exhibition to suggest that race is no longer an issue

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, No Need of Speech, 2018, installation view, ‘Fly In League With The Night’, Tate Britain

Art is not made in a social and political vacuum, argues Tom Denman, nor can it be exhibited in a ‘para-imaginary realm’ or, as in the case of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Tate retrospective, as if we live in a ‘post-black’ era in which race is no longer an issue.

Tate Britain would have us believe that its retrospective of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s brief career to date is politically no different from any other exhibition held at the museum since its foundation in 1897. ‘We live in a post-black world,’ the institution seems to be saying, ‘race isn’t really a thing; it probably never has been.’ It is as if black bodies had always been fairly represented on the walls of the building that black labour (by proxy of the transatlantic sugar trade) helped to build; as if the British-Ghanaian painter’s ‘para-portraits’ – to use Okwui Enwezor’s term referring to the way they depict ‘fictive’ as opposed to ‘real’ sitters – enacted a seamless continuity from the real portraits in the galleries across the hall, portraits that are, needless to say, the faces of Britain’s colonial past. ‘Fly In League With The Night’, as Yiadom-Boakye’s exhibition is titled, is remindful of Tate’s mollified portrayal of colonialism in its ‘Artist and Empire’ exhibition of 2015–16 (Reviews AM393) in that the whitewash wears thin. Why? There is an uncanny absence of conflict and an unwillingness to face up to the harsher realities of the UK’s past and their repercussions in the present and future. All this is in accordance with the myth of self-absolution and moral purity that the institution is trying to sell.

I could feel Tate’s rhetorical orchestration kick in before I entered the exhibition, in the stripped-back, wide-arched neoclassical hall, redesigned by architects Caruso St John 2007–13, which is aimed at establishing an atmosphere of atemporal neutrality. If the sense of universalism isn’t embedded enough in the architecture, it is felt strongly in Sir Steve McQueen’s Year 3, 2019, installed along the walls flanking the exhibition entrance – or at least in how we are encouraged to view the work, which consists of 3,128 class photographs of children between the ages of seven and eight taken in schools across London. The almost unanimous praise afforded Year 3 renders the work as a kind of celebratory feel-good statement, which is exactly how Tate wants us to think of it: everything’s fine, everyone’s smiling, life is beautiful etc. To no small extent the work is indeed a statement of hope, and a very affecting one at that, but as the Marxist ‘philosopher of hope’ Ernst Bloch argued, ‘the essential function of Utopia is a critique of what is present’. And in fact, McQueen’s work, once we ignore the publicity, is efficacious because it does provide such a critique. As Jes Fernie (Letters AM433) has pointed out astutely, ‘Tate says the work is a hopeful portrait of children who will shape the future, but you could draw a circle around the small number of kids who will get a chance to shape that future.’ McQueen’s ‘anticipatory illumination’ is set in real circumstances which he doesn’t try to hide.

I thought perhaps Yiadom-Boakye would effect a similar kind of critique, that somehow the claim that her subjects were ‘entirely imagined’, as Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson put it, was not as ontologically tenuous as it sounded and would lend the works a certain ungraspable – even fugitive – quality, that they would exist in a dimension both of and against the exhibitionary complex. But instead of such critique what I saw was assimilation, founded on the fact that ‘entirely imagined’ is an impossible proposition. Indeed, to claim that the subjects are entirely imagined is to wrongheadedly presume that the faculty of the mind that produces the images is shut off from the outside world; on a rudimentary level, it presupposes a clear distinction between the mind in which the images are imagined and the body which converts them into paintings. How can they be ‘entirely imagined’ if they’re also painted?

There is, however, a deliberate reason for this strange insistence that Yiadom-Boakye’s subjects materialise on the canvas by some kind of unmediated leap. As long as Yiadom-Boakye’s works are understood as having been produced in a vacuum, they can be contained as such, and the exigency of socio-political contextualisation can be ignored. It is clear that Tate uses ‘entirely imagined’ to account for the work’s apparent embrace of post-black, which Eddie Chambers has defined as an ideology paradoxically encompassing ‘art that seeks to undermine the role of race within black artists’ practices and yet also explore the black experience’. Tate quotes Yiadom-Boakye as saying, ‘I was always more interested in the painting than I was in the people’ and that she is ‘resisting a stereotype’ – but without explaining, or even asking, why she paints people in the first place or delving into the issue of racial stereotyping. In 2006, the Birmingham-based black figurative artist Barbara Walker produced a series of portraits of her son on backgrounds made of digitally enlarged ‘stop and search’ tickets that the police had issued to him after they’d stopped and searched him on numerous occasions just because he fitted a racial stereotype; not only are the drawings themselves profoundly moving, but they counteract a dehumanising – and stereotyping – official procedure by inserting a human face, the face of her son, that ‘defaces’ this procedure. Is Tate trying to imply (via Yiadom-Boakye) that such art as Walker’s, by being overtly political (as well as highly personal), in fact sustains racial stereotypes? We may never know for sure, as Tate would rather leave the ‘difficult’ issue alone, but the absence of intellectual rigour on such matters (precisely because they are difficult) arouses the suspicion that there is only a certain type of black artist the institution is willing to represent.

Tate might claim that Yiadom-Boakye does not wish to be ‘labelled’, as it did in response to Oscar Murillo’s expression of annoyance at the way Frank Bowling had been de-politicised in the institution’s retrospective of the latter’s 60-year career in 2019 (Bowling himself had stated, ‘It turns out it’s going to be a Tate show and not mine’); but this does not give automatic licence to the institution to use the artist as a pawn for its own utopian-propagandising, which is itself equivalent to an act of labelling – interpellative, dehumanising racial labelling of the kind theorised by Frantz Fanon (indeed, it puts a ‘white mask’ on a ‘black face’) – in terms that suit the institution to the detriment of the artist. It is what Sarat Maharaj called ‘multicultural managerialism’, in other words ‘control by fixing difference into static components of cultural diversity’. There is no arguing away the racial politics of this exhibition: if any artist paints black figures and those figures are exhibited at Tate Britain, there is no way that anyone can then say with any plausibility that the work doesn’t concern black politics. The political voice of the work might be quiet, but that of the institution could not be louder. Given this fact, Tate’s reluctance to engage with race and the problematics of exhibiting subjects historically subjected to racialised categorisation in an institution with imperial origins – while still exploiting such categorisation as moral capital for its own propagandistic agenda – strikes as being all the more deceitful. It is crucial that such subjects are permitted to hold their own, that they are at least given a chance to speak for themselves, even if their voice were to manifest as an active refusal to speak. But Tate would rather deprive them of this right and do all the speaking for them.

Yiadom-Boakye’s subjects inhabit a para-imaginary realm. They possess a certain quietude or even muteness, which their often larger-than-life scale, even when they are laughing or singing, manages to amplify. If we do get to hear their voice, we hear their breath and heartbeat. Perhaps her subjects are meant to enact what Fred Moten calls ‘refusal of what has been refused’ (and thus their quietude would be equivalent to a refusal to assimilate themselves into any objective standard of blackness at the bidding of institutional power); or Édouard Glissant’s notion of ‘opacity’, signifying the withholding of the self lest it be absorbed into the dominant power’s strategic or ideological agenda. Tate, though, has gone out of its way to pre-empt these effects, taking the quietude of Yiadom-Boakye’s subjects as express permission to speak on their behalf. Hence curator Andrea Schlieker is ever so keen to underscore the figures’ ‘respite’, ‘restraint’, ‘even temperament’, ‘quiet conviviality and contemplation’, ‘empathy’, ‘lassitude’, that they are ‘doing nothing’ and, best of all, that Yiadom-Boakye ‘posits tranquillity as a form of resistance, serenity as meaningful act’. Since when has tranquillity (which seems here to be cast in opposition to nonviolent protest), or doing nothing for that matter (unless in the form of a sit-in or labour strike, neither of which this is), ever worked as a form of resistance? Am I sensing an underhand rebuke to the Black Lives Matter movement?

Achille Mbembe, much of whose philosophy has explored the biopolitics of blackness, has written: ‘To produce Blackness is to produce a social link of subjection and a body of extraction, that is, a body entirely exposed to the will of the master, a body from which great effort is made to extract maximum profit.’ This is what’s happening here: reduced to bare life, or what Mbembe calls ‘surface simulacra’, Yiadom-Boakye’s bodies become iconographic grist for Tate’s ideological mill.

The subjects ‘happen to be black’, writes Farquharson, and the catalogue is intent on skirting and downplaying the issue, making additional, inexcusable blunders in the process. This is most glaring in two brief references to Édouard Manet’s Olympia, 1863, a painting invoked as part of the curators’ bizarre effort to situate Yiadom-Boakye in the pre-contemporary western canon (alongside, amongst others, Manet, Francisco Goya, John Singer Sargent and Rembrandt). First, Schlieker discerns a ‘kinship’ between the ‘symphony of greys and whites in the shirt-folds’ in Yiadom-Boakye’s For The Sake Of Angels, 2018, and ‘the two large pillows’ rested on by the nude woman who is the central subject of Manet’s picture. Co-curator of the exhibition Isabella Maidment compares the paintings again, this time observing that the ‘overall palette’ of Yiadom-Boakye’s picture is ‘evocative of the notorious disjuncture between whiteness and blackness in Édouard Manet’s Olympia’. What this disjuncture is and why it is notorious is left unexplained: the obvious and only significant link between the two pictures is ignored. I can only presume that the notoriety to which Maidment fleetingly refers has something to do with the black maid who appears behind ‘Olympia’, but the curator is so vague on this matter that she may as well only be alluding to the shocking intensity of Olympia’s white flesh against the dullish (blackish) background, which, after all, gained enough notoriety on its own in 19th-century Paris.

This is no ordinary matter of formalist myopia (the connoisseurial judgement of which is far from watertight), but it is deeply revelatory of Tate’s institutional mindset. In an oft-cited 1992/94 essay, Lorraine O’Grady (see Reviews p27) called out Manet’s depiction of the maid (modelled by Laure, whose full name typically has eluded the archive) and the picture’s subsequent reception as representing both the desexualisation and objectification of the black female body, an issue exacerbated by the critical negligence to which she has been subjected in favour of the ‘empowered’ white woman holding centre stage. ‘Forget “tonal contrast”,’ O’Grady writes, ‘We know what she is meant for: she is Jezebel and Mammy, prostitute and female eunuch, the two-in-one […] And best of all, she is not a real person, only a robotic servant.’ In order to avoid the ‘difficult topic’ of race, Tate draws the line at ‘tonal contrast’. The institution thus effects no less than a continuation of the violence inflicted on Olympia’s maid (violence amplified by the fact that the oversight occurs in the context of an exhibition of paintings of black people in a major national institution with colonial origins and seems to have been calculated to assuage racially oriented discourse), violence which, as O’Grady explained, is symbolic of its continued manifestation well beyond the realm of pictures. This same violence is evident in the way Tate seizes on the quietude of Yiadom-Boakye’s subjects, rendering them more mute than they already are (as ‘surface simulacra’), with repercussions for perceptions of the black body in general.

The danger of post-black ideology, Chambers has explained (in an article regarding its propagation in the US), is its ‘fiendish entanglement with postrace’, the bogus ‘theory that the United States has transcended racial inequity’, which became especially popular while Barack Obama was US president. This makes it all the more disquieting, in a way, to see a post-black exhibition after Obama, in the autumn of Donald Trump’s presidency which, along with the worldwide proliferation of Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd, had shattered many liberals’ illusions of post-race. While the Yiadom-Boakye exhibition may have the veneer of an act of racial inclusion, because of its harnessing of post-black, the opposite is closer to the truth. As Chambers observes, post-black is, in effect, a neoliberal policy of exclusion: ‘There is now a post-black authoritarianism that dictates what sort of black artists, and which practitioners in particular, get exposure.’ It would come as no surprise, therefore, that Yiadom-Boakye was the only black artist in Tate Britain’s 2018 group exhibition, problematically titled ‘All Too Human’, focusing on the human figure in 20th- and 21st-century British painting and, to lesser extent, sculpture. Friedrich Nietzsche aside (the title comes from a book of his), the message is clear: because Tate feels it can assimilate her (along with the Goan artist FN Souza) into its monocultural vision of art history – which in this exhibition stands for humanity – she can be included, but as for the rest … Indeed, Tate Britain’s favouring of Yiadom-Boakye signifies a deliberate decision not to show other British black artists whose careers have spanned a much longer period and have without question been far more impactful on art, culture – and politics – in the UK, such as, for instance, those associated with the BLK Art Group such as Sonia Boyce, Donald Rodney or Keith Piper, who emerged in the 1980s. Tate Modern’s forthcoming retrospective of the career of Lubaina Himid, an artist closely involved with this group, might be a step in the right direction, but the institution’s treatment of Yiadom-Boakye – as well as, just as importantly with regard to Himid, its way of skirting the ugliness of colonialism in its ‘Artist and Empire’ exhibition – leads me to ask whether the element of critique that is so crucial to Himid’s work will be given the foregrounding it is due, or whether Tate will tap into the theatrical element in order to treat the show as yet another cause for propagandistic celebration and self-congratulation. Why would artists such as those I have cited be overlooked? The reason is simple: their art deals unequivocally with racial politics in a way that would be considered ‘uncomfortable’ in the firmament of the art establishment. (I wonder if it wasn’t for such reasons that Bear, 1993, described by Rianna Jade Parker as McQueen’s ‘most overt commentary on issues of race, masculinity, and homoeroticism’, was excluded from his 2020 retrospective at Tate Modern.)

The resounding assertion made throughout the exhibition’s catalogue, and in its glowing reception in the press, that Yiadom-Boakye’s ‘style’ continues from – and, they claim, constitutes a break with, even a subversion of – 19th-century ‘moderns’ is not only spurious in itself, but is also an act of this same kind of exclusion amounting to an egregious gesture of neo-colonial oppression. Not only does the exhibition catalogue erase the history of art from c1900 onwards, but, more importantly, it fails to account for the contribution of black artists to this history. It is as if nothing happened between Manet and c2000 and then, all of sudden, Yiadom-Boakye materialised as the first black painter. This goes beyond post-black. This is never-black. This is never-race. This is not saying that we have ‘transcended racial inequity’, this is saying that such inequity never existed. Tate chooses Yiadom-Boakye to the exclusion of British black artists perceived to be difficult not only because those artists are unabashed about their political engagement, but because they refuse to be extracted from the history of which they and their work are a part; there is no way, for instance, of extracting Barbara Walker’s drawings of her son from the history of police racism in the UK. In other words, those artists will not be subjected to chronopolitics, what Johannes Fabian in his 1983 book Time and the Other described as the denial to the Other of a place in the contemporary world.

Jean Fisher has written: ‘Genuine inclusion requires an institutional mindset prepared to reconfigure British society in a multicultural way, in effect a redistribution of power’; otherwise, she goes on, what we see is ‘hegemonic containment’. Yiadom-Boakye is irresistible to Tate because the institution finds her easy to contain, as seen in this exhibition and in ‘All Too Human’. It is significant that Fisher was writing with reference to ‘The Other Story’, a landmark exhibition curated by the Karachi-born artist Rasheed Araeen (Interview AM413), which opened at the Hayward Gallery in 1989 (Reviews AM133). The express purpose of this exhibition was ‘to demonstrate and legitimise the suppressed history of a modernist aesthetic among British visual artists of African, Caribbean and Asian ancestry’ (I should add here that it was wildly remiss of Tate to exclude Araeen’s work from ‘Artist and Empire’, given his vital role in uniting and exhibiting artists from the Commonwealth who otherwise struggled to gain admittance into the art establishment). But in all this there was an awkward paradox in ‘the implied desire for inclusion in and approbation from a system regarded at the outset as unjust and corrupt’, hence there was the need, identified by Fisher, for social reconfiguration that would allow genuine inclusion to occur. The exigency to which Fisher refers thus goes far beyond the issue of who to include and who to exclude. Social reconfiguration must penetrate the institutional mindset; it calls for critical engagement with the difficult, contextual problematics underlying any exhibition of the historically racialised body in an institution such as Tate Britain, without which all an exhibition such as this one can amount to is a show of colour-coded managerialism.

It has not been my intention here to ‘cancel’ Mr Tate, but the relation that this country’s history has to the local and global present – not unlike the relation between the psychic and the social – is fraught, violent, unctuous and forever impure. As Dan Hicks, curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, urged in his recent book The Brutish Museums (Reviews AM443), it is the responsibility of museums to acknowledge this impurity, and I would add that this goes for all national institutions of such stature as Tate Britain, regardless of how much they have to do with the histories of extractive colonialism. And by acknowledge I do not mean tokenistic notices of goodwill or sympathy (or webpages saying, ‘Yes, we know, but…’), but considered, self-reflexive critical engagement. Denial amounts to a continuation of colonial violence, and Tate’s disingenuous co-option of the black body seen here amounts also to the kind of biopolitical and chronopolitical manipulation that is at the unrelenting heart of such violence. Tate has found in Yiadom-Boakye a gift for its own – and by proxy, this country’s – agenda of self-absolution, and even if the whitewash wears thin, the damage this does, through the lies it upholds, is lasting. The spectre of Olympia’s maid haunts every room.

Tom Denman is a writer based in London.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s exhibition ‘Fly in League with the Night’ ran at Tate Britain, London from 2 December 2020 to 31 May 2021 (with closures for Covid-19 tier 3 restrictions) and again 24 November 2022 to 26 February 2023.

First published in Art Monthly 446: May 2021.