Feature

Eco Art

Dean Kenning on art energy in an age of ecology

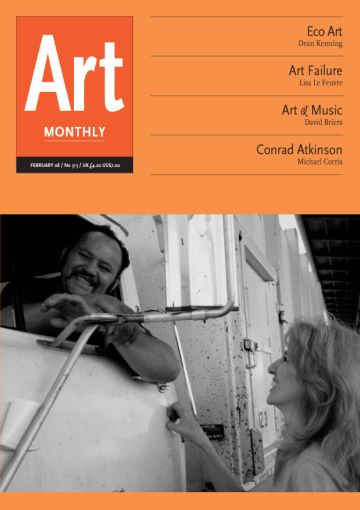

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Touch Sanitation, 1977–84

Art’s inherent energies are dissipated as soon as it is called upon to support a cause. God forbid that there should be an ‘eco art’. This does not, however, mean that art has nothing to say about the issues which will dominate global politics as the earth warms up and the sea levels rise. On the contrary, artists have long been concerned with the fundamental political questions now being posed by a new ecological consciousness: questions of ownership, distribution, necessity, non-monetary value, national borders, etc; questions not so much of the exploitation of natural resources but of how this exploitation becomes an instrument of injustice and inequality.

But the artistic as opposed to the ecological concern is really a concern with nothing but art itself, with the issues as ‘material’. As ecological awareness instils in us a sense of waste, the finiteness of recourses, and the myriad costs of production and supply, shouldn’t we then question the continued existence of objects and activities which seem excessive to our basic needs? At this point we remember our dependency on ‘symbolic energy’ without which, according to Roland Barthes, we would die. Bound to search for and invent meaning, the human animal, while remaining part of nature, is ontologically ‘out of balance’. The important point is that while people long for something they can believe in, it is this same excessive, restless force that also disrupts all social systems and hierarchies which justify their authority by way of a ‘natural order’ – from the ‘great chain of being’ to the ‘law of the jungle’. A political reading of art sees it not as a proliferation of unique objects cast from the minds of self-possessed creators, but as a practice which is an over-determined force field of social, cultural and other ‘external’ factors which impinge on meaning. These factors will then be captured as energy – to the extent that they are confronted, grappled with and challenged – or else lost, to the detriment of artistic activity, as long as they are ignored or comfortably accepted.

Given this, I will propose that art energy today is derived from two sources. Firstly, an antagonistic identification or ‘taking sides’ with the low, the debased, the outcast, the ‘losers’ which initiates a ground-level, materialistic, symbolic exploration against prevailing codes of status, success and morality. Secondly, a rejection of the commodity status of art in favour of a symbolic activity which takes place between real people, in the real world, over time, necessitating a move away from the isolated art object.

I want to pursue the notion of ‘art energy’ in an age of ecological consciousness by way of three very different exhibitions which opened last November. ‘Green Dreams’ at Kunstverein Wolfsburg examined the present moment while casting a wistful glance back to a time of art-ecology synthesis, via a strange pair of German Green Party posters for the 1980 elections. Both Andy Warhol’s parody of celebrity endorsement and Joseph Beuys’s photo of a toy soldier aiming point-blank at a looming hare seem designed to delay, to ‘hold up’ the message of the text (vote Green) rather than confirming it in the manner of standard publicity. Beuys’s involvement with the Greens was not separate from his other activities but part of his ‘energy plan’ to replenish ‘spiritual needs’. He once called his sculptural objects ‘waste products’, declaring teaching to be his greatest work of art. Disposing of such waste on the art market in fact allowed him to fund the Free University. Warhol seems so different, but was he really? Isn’t it the case that all those screen prints he churned out were a kind of waste product which enabled him to maintain, to nurture his greatest artwork The Factory? This was a living system, a dynamic energy field drawn from lowlife ‘superstars’ and cultural outcasts, feeding back in an ecstatic chain reaction of multiplying symbolic expenditure, perverse ‘unnatural’ meanings.

To think of art primarily in terms of a unique art object, particularly after conceptualism’s technical deskilling, is to isolate it from the living relational and inter-productive processes without which it could not exist. This is good for market value but bad for art energy. The best work in ‘Green Dreams’ combines an ecological awareness of how apparently separate things interconnect with an emphatic move away from the art object and its preciousness in a way which openly confronts art’s social function. Julika Gittner’s bulky agglutinations (Economic Units & Daily Allowance, 2002) made from used batteries, plastic bottles, old potatoes and other rubbish held from bursting in swathes of cheap carpet are present in the gallery, but above them are photos of individuals holding these same sculptures. Each one, it turns out, represents the person’s ‘unique’ average daily consumption of energy, water, domestic floor space, etc. The fact that clear statistical data could spawn such monstrous sci-fi amoeboid analogues suggests the symbolic excess that pertains amidst the banal ordinariness of life. The art itself exists elsewhere, beyond the decaying physical manifestations.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles is represented in the show by two videos from her Touch Sanitation project. These are not autonomous ‘video works’ so much as documentary elements of extensive research and public performance carried out over a number of years. The subject is waste, which really means people – all of us who produce the rubbish and those who are assigned to deal with it, because as Ukeles writes in her open letter to the ‘sanman’ (‘sanitation worker’, American for ‘dustman’) ‘making waste is the surest sign that we’re alive. Dead people do not make anything.’ And so an ecological issue of waste management is recognised as a most basic question of social organisation, of civilisation, moreover one fundamentally concerned with responsibility, status and how work is valued in a capitalist system. The problem Touch Sanitation confronts is how to celebrate necessity, and this is tackled via the structural prejudices of a childish individualism where, as Ukeles writes to the sanman, ‘people want you to be their grown-up’; and so she sets out to create ‘hand-energy’ by shaking hands with every single sanitation worker in New York City, and to look them in the eye because, unlike social servants like the police and fire brigade who are there to ‘handle things gone wrong’, the sanmen are despised for ‘handling the “normal”’, and in a strange way only become visible when they do not appear and the rubbish starts piling up. The constant refrain amidst the grievances of the workers who are given a voice in Ukeles’s Sanman’s Place video is ‘I am not garbage; I collect the garbage’. But for Ukeles her ‘fieldwork’ is a lesson ‘in the NEW way we will all have to act on planet Earth’. These concerns go back to the artist’s original ‘maintenance art manifesto’ from 1969. This proposed a dialectic of Death Instinct (‘individuality; Avant-Garde par excellence’) and Life Instinct (‘unification’) translated into two basic systems of Development and Maintenance. While both systems are necessary, and are infected with each other’s ideas, the value of maintenance is systematically repressed in both art and culture generally (‘lousy status [for] maintenance jobs minimum wages, housewives = no pay’). A great division of labour sustains the art system as a microcosm of society, and by focusing on the unglamorous back-breaking, mind-numbing side of life not only is the value of maintenance and its repression highlighted, but the conventions of art are subtly undercut (‘keep the dust off the pure individual creation’). Such disruption of unsatisfactory (false) art norms is the a priori of art energy, and it is striking how sustainable Ukeles’s maintenance art has been as she has pursued it so modestly and determinedly in various projects since; how relevant and searching it seems today compared with the formula-repeating, art star fate of so many of her conceptualist contemporaries.

‘Green Dreams’ pretty much lets the work do the talking, but in London two shows took emphatic pro and anti ecological agendas. ‘Fusion Now! Art and the politics of energy’ at Rokeby was curated by JJ Charlesworth in association with the Manifesto Club, a coalition of intellectuals who ‘challenge today’s downbeat over-regulated culture’ and ‘aim to set the agenda for a twenty-first century Enlightenment’. The exhibition is framed in terms of championing nuclear fusion, a technology promising the twin panacea of abundant fuel with zero carbon emissions, but the wider mission is to take a stand against puritanical anxieties over abundance and calls for restraint by an environmental ‘cultural elite’ responsible for a ‘conspiracy of silence’ over how the human race might produce more: ‘More light, more power, more people. And more art.’ The first thing that jars is how this discourse assumes a position of marginality but actually backs a winner. Billions of euros are being pumped into Europe-wide fusion research. Its estimated operational use is decades away; in the meantime the UK government seems likely to push through new generation nuclear fission with an accustomed lack of democratic consultation. If the Manifesto Club is not the cultural wing of New Labour, it shares a similarly weightless rhetoric. Artists are prompted by Charlesworth to ‘take sides’ in the battle of ideas between austerity and plenty, restraint and potential, more and less. These are undialectical ideals rather than material realities. By contrast, an ecological thinking that makes it past the recycling bin is immediately confronted by questions of ownership, profit and inequality. Plenty of what, and for whom? Who benefits and who pays the price? How does more of one thing lead to a lack of other substantive goods: poor health caused by toxic pollution, a lack of humanity in factory farming, time lost working excessive hours in order to produce and consume more to the detriment of exploratory symbolic activities like art, etc?

The potential for a realistic transformation of society is condensed in disparate ecological concerns: it is in the fight against specific injuries and inequalities; it is in calls for more effective regulation and democratic control over the untrammelled power of corporations; in other words it is in the drawn out, ground level antagonistic disputes and negotiations where the hope for a more equitable world lies, and where nascent alternatives to consumer culture can be tried out. The dogmatic attachment to ‘progress’, exemplified in James Heartfield’s catalogue essay, means that decrepit optimist ‘capitalist contradictions’ must be wheeled out to play stooge for the Manifesto Club’s radical credentials. The frantic pursuit of profit, we are told, has abolished the basis for the capitalist system itself, and so presumably we await a cabal of technophiles to prize ownership from the hands of business by sheer force of argument, before establishing their five-year plan.

What do the artists think about nuclear fusion, the joys of progress since the Industrial Revolution, the Green conspiracy, or any of the other issues that form such a central aspect of ‘Fusion Now!’? We do not know because they are unable to speak. Their works are presented like ‘exhibit a, exhibit b …’, examples of the art we want more, more, more of – but not too much please in this gallery – and all preciously spaced apart according to the commercial white cube norm; alienated from the framing agenda, from one another, and from the artist’s own thoughts in time. So much for nuclear power – this show had all the energy of a Cork Street art boutique. Indicative is the fact that the two video pieces (Ivy meet Mike, 2007, by Mark Titchner, and Kalmar Received a Great Deal of Attention (1974), 2007, by Liam Gillick) – video being a medium which potentially commands an engrossed temporal engagement – both appropriate historic events as a kind of test card conceptual decoration. John Latham clearly had a lot of ideas regarding the relationship between world politics and nuclear physics, but his sculpture God is Great, 1990, functioned primarily as an atomised relic of a body of thought. The lumpy thing on the wall (Elf Power, 2007, by John Russell), one of the artist’s brave-new-age digital prints which he had uncharacteristically solidified by wrapping it around bits of wood and polystyrene, was perhaps an ironic comment on all these objets d’art. More than anything else, an artwork is a manifestation of a particular approach to the world. Its methodology is exploratory and speculative. Picture it less like an owl of knowledge surveying the scene from a superior vantage point, and more like an amoeba sending out probing pseudopods, groping and negotiating, palpably experiencing the friction of life. It would seem to be well qualified to trip up the seamless teleology of progress presented by advocates of the new Enlightenment. So while ‘Fusion Now!’ claimed to be political, and in some sense was, it served to depoliticise art by co-opting it to a positivist discourse that starts from a position of already knowing the answer – a discourse, that is, anathema to art’s production of meaning.

There is a wider issue here which we may call the contemporary crisis of meaning. The justifiable collapse of faith in progress and aspects of parliamentary democracy which turns people towards new age fads and cults, superstition, nationalism, ethnicity, radical versions of established religions, or indeed extremist ecological ‘back to nature’ utopias in a search for identity and meaning, is symptomatic of capitalism’s inability to satisfy our ‘spiritual needs’. Rather than setting the poor lost souls back on the straight and narrow, art is able to tap into the truth of this spiritual hunger, to express the (sometimes dark) reality of these identifications, and to turn the multitudinous and fascinating symbolic material to anti-authoritarian ends through its anti-rationalistic but dialectically grounded approach to questions of truth. At a moment of albeit superficial visibility for art, it might be hoped that this approach could be of more widespread inspiration and value.

A sense of interesting new times was in the air at ‘Climate of Change’, an artist/activist-led project which, although assertively ecological in outlook, also embodied a transformational spirit with regards to art itself – specifically opposing the exclusionary economy of the London art scene with an open submissions policy. It took place in an enormous three-storey warehouse, but was terminated abruptly less than two weeks into its run when the leaseholder ASC Studios put padlocks on the doors citing ‘health and safety’ – an instance of how regulation in its specificity, just like deregulation, is designed to work in the interests of existing power and property ownership. Inevitably given the nature of the show there was much use of cliché, sloganeering and message-heavy satire, but it existed amidst more knowing work which latched onto ecology less as a concern which demanded expression, and more as a foothold by which to explore more intrinsically artistic questions. At the bustling opening a poet on the activist stage berated the multinationals to an already converted audience; meanwhile Bob & Roberta Smith’s Apathy Band had, significantly perhaps, stationed themselves outside. Their very name forces the utopian aspirations which underpin art’s progressive claims to collide with the fact that art is a marginal pursuit with mixed results. But the glory of ‘Climate of Change’ was the sheer promiscuous chaos of over 100 artists’ works self-installed in a higgledy-piggledy way wherever space was available. The social energy also played out with artists who used the situation as an opportunity for extended conversation, interaction and the production of work over time, an example being Paul Sakoilsky who re-engineered London’s restlessly regenerating newspaper headlines from his live-in Dark Times office. But for all the rejection of standard art world competitive individualism, one wonders how strong the bonds of such a disparate medley of artists could be, and in fact whether the shutting down of the show was not a test case for a true solidarity that never materialised.

If art, like ecology, is intrinsically faced with the question of equality, then perhaps we should adopt Jacques Rancière’s notion that the essence of equality is not to unify but ‘to declassify, to undo the supposed naturalness of orders and replace it with the controversial figures of division’. Art energy is then that excess produced simultaneously as an outcome of fission (division) and fusion (union). Rather than insipid visions of harmony where contradictions disappear, art’s final lesson might be a dialectic where antagonism and alliance, subjectivity and society, development and maintenance are no longer seen as opposing goals but each the necessary condition of the other.

‘Green Dreams’ was at Kunstverein Wolfsburg 17 November 2007 to 10 February 2008. ‘Fusion Now’ was at Rokeby, London 21 November to 20 December 2007. ‘Climate of Change’ was at 235-241 Union St, London in November 2007.

Dean Kenning has curated ‘New Dark Age’, opening in March 2008 at Hats Plus, London.

First published in Art Monthly 313: February 2008.