Report

France on Germany

David Lillington on the row over a French show of German art

4 April. Adam Soboczynski of Die Zeit launches his attack. After a long introduction in the most elegant German journalistic prose, he moves in on his target: ‘De l’Allemagne’ (On Germany), the Louvre’s exhibition of German art from 1800 to 1939. His article has a provocative title: ‘Auf dem Sonderweg’ (‘On the Special Path’). His chief complaint is that the exhibition makes it look as though Nazism was inevitable, and as if the art itself was implicated, from way back in the 19th century, in a march towards the Second World War.

The Sonderweg was the idea of a form of progress particular to Germany, one which didn’t, as in France, involve a revolution. Originally intended as a positive idea, it became with Nazism the idea of Germany as a nightmare. There seems no doubt that the curators of the show were genuinely shocked by the Die Zeit article. The question here is should they have been shocked? What went wrong? And what are the implications for the curating of exhibitions?

6 April. Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel in the Frankfürter Allgemeine Zeitung. Her article is called C’est le Sonderweg. She is French – a point noted in subsequent debate – and a curator at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris: ‘It’s this suggestion of an unavoidable German catastrophe, which all this darkness and Romanticism seems to point to, which makes the political subtext of this exhibition so irritating.’

8 April. Niklas Maak, also in the Frankfürter Allgemeine Zeitung. Just as angry, but more surgical. Then the director of the Louvre, Henri Loyrette, defends his exhibition in Die Zeit. He reiterates the show’s aims: its three sections examine German art’s relationship to the past, to nature and to people. He does not address the point that the show seems primarily to be about the German national identity. He denies any intention to link Romanticism with Nazism. Co-curators Danièle Cohn and Sébastian Allard also issue defences. On 14 April Bernhardt Schulz of Der Tagesspeigel tries to pour oil on troubled waters. And so on. On 18 April Le Monde publishes a survey of the argument so far. By 4 May there have been over 20 articles on the exhibition – and the argument – in French and German newspapers.

Maak’s article has a title which rhymes and is provocative: ‘Aus Tiefem Tal zu Riefenstahl’, which translates as ‘Out of Deep Dark Valleys, to Riefenstahl’. And it is a title that sums up much of the criticism of the show, which is accused of being ‘teleological’. He thinks the exhibition shows a Germany of the Brothers Grimm. And he writes, ‘If exhibitions are indicators of the cultural climate, then the dark end of this show (which is in other respects worth seeing) – the picture of Germany as a country alienated from all European development, as an untransparent, obscure, naturally violent power – is perhaps also an image of the estrangement that has taken place in the field of politics.’ So he raises, in addition to his criticism of the curation, a question about France’s attitude to Germany. Soboczynski and Lamarche-Vadel do the same, raising the stakes somewhat.

However, it is the (admittedly related) question of the curation – and what went wrong with it – that interests me; the question, among other things, of ‘teleology’. This is an old issue. Benjamin Binstock, in his preface to Aloïs Riegl’s Historical Grammar of the Visual Arts of 1897-99, writes, ‘we might characterise Riegl’s system as teleology without telos (goal) ... Riegl ... distinguishes his outlook from Hegel’s ... and reminds us of the impossibility of escaping Hegel ... when he objects to one scholar who “seeks the principle of coherence not in the work of art itself but in the prevailing parallels with the development in politics and the spiritual life of different peoples”.’ This is precisely the criticism levelled at ‘De L’Allemagne’.‘Riegl acknowledges Hegel’s essential insight into the connection between culture and history but opposes those who interpret art mechanically as an illustration of history ... Nor is the principle of coherence to be sought in the supposed historical function of the work.’

Another art historian who would have taken issue with the exhibition was Werner Hofmann, who died on 13 March this year. His famous chapter title ‘Nationen malen keine Bilder’ (‘Nations do not paint pictures’) seems almost provocatively contradicted by this show’s DVD, which begins with the words, ‘Paintings can tell the story of a nation’. ‘Artworks’, Hofmann says in Wie deutsch ist die deutsche Kunst? (How German is German art?) of 1999, ‘do not allow themselves to be tied to national character.’ With such a book available to them, Soboczynski suggests, the curators should have known better.

Andreas Beyer, the senior of the two German curators (there were five altogether, three were French), was interviewed by Soboczynski and claimed that when interpretation and the hang came under discussion, he was excluded. For the interview, the pair meet in a Parisian cafe, the Brasserie Vagenende. The art nouveau décor, and the mirrors, are described. Beyer sounds agitated. He talks quickly and displays ‘an unusual combination of anger and cheerfulness’. Even the cake he eats is mentioned; it is like a spy novel. When you turn to the French Le Figaro, you see that Beyer ‘confie au Figaro’ (‘confides in the Figaro’). So their scoop is also exclusive: clearly he has an axe to grind. However, he ‘doesn’t want to pour more oil on the fire’. Then: ‘what does it matter what we think? The artworks are beautiful, strong, interesting. You must go to this exhibition, where you will learn a lot about German art.’ (I can endorse all that.) ‘However my conviction remains that you cannot tell the story of a country or a people through its works of art.’

The anger in the newspaper articles conveys a love of art, and a view of it as autonomous and complex. My own notes read ‘not a show that takes the viewpoint of the artist’. Soboczynski writes: ‘the artworks are presented as standing for the construction of the German nation ... The exhibition, from the first room onward is dominated by the themes of the Apollonian and the Dionysian – extremes which Germany obviously and at all times and without resolution was fighting with.’ Perhaps the most vivid criticism is Maak’s: ‘the art looks like flotsam and jetsam carried on the river of fate.’ What is more, it is carried ‘without influence or protest’.

This was a show about the German national identity. So it was not really a survey of German art, but it was nevertheless natural to see it as such, or think it should be, since it was a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Traité de l’Élysée, a friendship treaty between France and Germany. And it kind of was. But wasn’t. So the problem was right there at the outset. The curation was double-minded, which is what the very first review said, in the Suddeutsche Zeitung on 28 March: ‘Especially noticeable is the double logic of the exhibition, by which Goethe’s colour theory and natural philosophy are mounted in the frame of the story of the fate of the nation. Goethe is at the same time at the heart of the show and somehow a foreign body in it.’ Although the writer, Joseph Haniman, does say that while the show is oversimplified, he thinks it avoids drawing a direct line from Romanticism to Nazism.

You would think alarm bells would have gone off as soon as it was proposed: ‘We’ll do German national identity up to the Second World War, and art’s relationship with that. In Paris. And we’ll open with ten paintings by Anselm Kiefer.’ That was another thing the Suddeutsche Zeitung picked up on. With the Kiefers, it said, the show went into Schieflage – it went awry. Indeed. You were obliged to enter, and leave, through a round gallery filled with a ten-piece Anselm Kiefer series (in which the word Maginot, rhymed, so to speak, with Atlantik Wall, and so on – perhaps you can imagine). What were they thinking of?

The exhibition catalogue is excellent, and has been criticised little. But the first essay, by two of the curators, Allard and Cohn, is problematic. It is mainly about the commitment of the Germans to myth, to what is unreal, to romantic ideals. The French, they point out, had Realism – with syphilis and poverty. The Germans sowed dreams – and would reap a nightmare. That is the message. The rottenness ran all the way through the art as well. At the very least, the art illustrated it.

It is not that the idea of German history as articulated in the show had no validity. And in the 19th century German politics and culture were indeed bound up with one another, and national identity was a subject of discussion as much as a subject for literature and art. You could say the curators of ‘De L’Allemagne’ tried too hard to be consistent about a genuine line in thinking and art. The result was firstly that it meant missing out huge chunks of German art history, secondly that the art and the political thinking were bundled together, and thirdly that some artists who had been pushed into this national identity rubric looked uncomfortable. To me the works of Käthe Kollwitz, for example, looked utterly out of place. These are the reasons journalists called the show poisonous. And an exhibition is an object in its own right, with its own language. It is not a catalogue; it has to present its art in its own way. ‘In short,’ concludes Soboczynski, ‘one has to exclude the concept of the exhibition in order to enjoy the work.’ Maak seems to think not just that the art is being used to illustrate something, but that the curators think the art is the ideological movement, or part of it, or was once part of it – is its flotsam and jetsam, washed up in the Louvre.

As for whether Nazism was inevitable – some do believe this. AJP Taylor did, as he made clear in The Course of German History, published in 1945. He was criticised but, in 1961, he wrote an unrepentant preface to a new edition: ‘It was no more a mistake for the German people to end up with Hitler than it is an accident when a river flows into the sea.’ Yet he also wrote, ‘On almost every test of civilisation – philosophy, music, science, local government – the Germans come out at the top of the list; only the art of political behaviour has been beyond them.’ He clearly separates art and ‘political behaviour’.

Perhaps the wall texts caused the biggest problem. Even while I was there I heard a French woman saying to a friend: ‘It isn’t right that they can say these things. It isn’t true.’ And you felt you needed to read them to understand the juxtapositions of paintings and rooms. Some examples: after the German victory of 1871, one text read, ‘antiquity became charged with an unprecedented vitalism embodying the power of primitive impulses’. And: ‘A Dionysian Greece established itself in Bismarkian Germany.’ Around this point Soboczynski identifies a central ‘poison room’. Another wall text read, ‘The case of Böcklin is the case of Germany’, but it did not explain the context of this. The source, as an essay by Thomas A Gaehtgens in the catalogue makes clear, is a book of 1905 by Julius Meier-Graefe in which he argues that Germany could afford to be more avant-garde. He means, ‘look at France, they have an exciting Avant Garde – and we have Böcklin’ (who was a grand old man at this point). Carl Vinnen responded, saying, no, let’s be what we are! Let’s keep our Germanness. A group of artists, writers, collectors and art historians – spearheaded by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, and including Wilhelm Worringer, Ernst Cassirer, August Macke and others – responded to Vinnen saying, ‘no, Meier-Graefe is right’. We doubtless are on the side of those signatories. But where were they in the exhibition?

Some Germans were resentful of the French Avant Garde, and there might have been a conservative museum policy, but there was opposition to that – including Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter and then Dada, the Bauhaus – all of which were absent, which is where the attempt to do a show about German art and German identity began to turn sour.

One wall text explained how Caspar David Friedrich’s Tree with Crows, 1822, is really about German national identity (or that is the implication) because the tree is on the burial mound of an ancient pagan warrior. But surely artists such as Friedrich wanted their paintings to be for the future, and open to interpretation. Painters of his ilk believe there is power in their work that even they cannot discern. In the catalogue for the ‘Dark Romanticism’ show down the road at Musée D’Orsay, Mareike Hennig writes: ‘The Romantics themselves were aghast at the abyss opened up by Friedrich’s paintings. What upset Clemens Brentano, Achim von Arnim, and Heinrich von Kleist about The Monk by the Sea, for example, was not so much what the painting actually showed, but “what I myself was supposed to find in the painting”, and which could apparently be found only “between myself and the painting”.’ That’s more like it.

Michel Crépu in his defence of the show (Die Zeit, 11 April) attacks Soboczynski for criticising supporting items. He agrees with him that the audio guide is not good, and in a journalistic flourish suggests throwing it out of the window into the Seine. We should not review audio guides, he says, ‘but collections of paintings’. It is a valid point. Nevertheless, it is fair to review the way the paintings are presented to us, and the fact that every manifestation of this presentation is different might suggest something about the organisation of the exhibition as a whole. The DVD has its own title: Germany: the Art of a Nation. It is about German political history, with art used as illustration. Its insistence that ‘paintings can tell the story of a nation’ would make Riegl and Hofmann spin in their graves. The ‘impulses’, which in the wall texts so annoyed the journalists, reappear. The problem is that the ‘primitive impulses’, apparently visible in Böcklin, von Stuck and others, are equated with those that – it is said – led to Nazism. So painting and political movements are merged, are seen as different expressions of one vital, destructive force.

The debate – enough articles to fill a book – with all its subtleties and observations, constituted almost an artwork in itself. My own feeling is that running like fear, like poison, underneath it all, is the sense of the loss of values built up after 1945, the loss of the Stéphane Hessels of this world – Hessel who wrote Indignez-Vous in his old age, and who died earlier this year. It is not the Germans coming, or the French. The fear is more general: of an encroaching and profound conservatism.

‘De l’Allemagne: 1800-1939: from Friedrich to Beckmann’ was at the Musée du Louvre, Paris 28 March to 24 June 2013.

David Lillington is a writer and curator based in London.

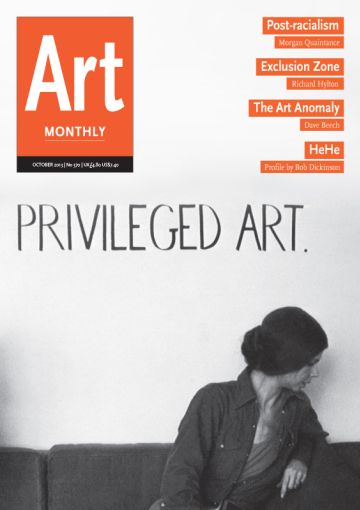

First published in Art Monthly 370: October 2013.