Feature

Glitch Poetics

Nathan Jones makes new sense from non-sense

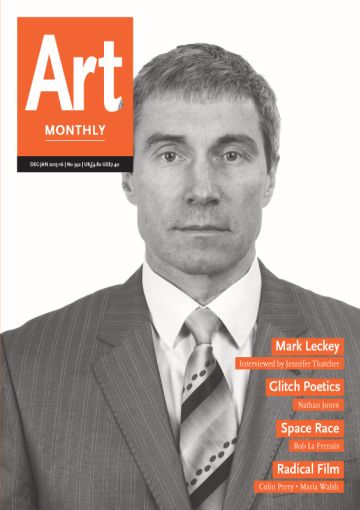

Erica Scourti, Glitch Poetics, 2015, performance

Technological breakdowns stop us at the moment of dissolution into a mesh of media, tools and technologies, offering us a fleeting moment of insight about the things we use and how we relate to them. In this sense, our experience of media is precisely – and perhaps uniquely – the experience of their failure. Several artists have made speech and writing the site of this revealing potential, proposing language itself as a form of media subject to similar failures and breakdowns.

Artists who have made language demonstrate such ‘glitches’ include Caroline Bergvall, who emphasises the talking face, Erica Scourti, who focuses on over-identification with the predictive text function on her iPhone (Profile AM382), and net artist Mez Breeze, who generates mischievous code/poem text works. These artists force and accentuate errors in language, whether in speech or writing, to extend what language can say into the formerly unspeakable territory of its own production. Cross-media artists such as Ryan Trecartin and Jennet Thomas also dramatise the crisis of the human thrown up by the enmeshed nature of information technologies and cognition – a context presupposed by the current increasing financialisation of our social practices through social media. These speculative ‘post-human’ artworks, by extending into the physical body such linguistic devices as metaphor and allegory, produce bizarre and dissonant effects – exhibiting an interesting aporia at the heart of what is often described as a ‘virtual reality’. Together, what I am calling glitch poetics operates to extend and make critically available the liminal moment of our relationship with technologies through language.

Bergvall’s 2004 work About Face restages the moment a performance of hers is disrupted and distorted by the apparatus of speech and the devices used to record it: ‘I had just had a painful tooth pulled out and could read neither very clearly nor very fast. Tape players with German and English conversations on the text were circulated among the audience. It took 45 minutes to perform the materials. For its second showing at Bard College, I speeded up the tapes, transcribed the snaps of half-heard materials, and integrated these into the performing voice … By now, it took ten minutes to read.’ Inhabiting the accidental slippage and the inherent noise of analogue recording as purposive tactic, this performance literally becomes ‘about face’ as frequent and irregular ruptures of silence speak of the often physically painful experience of uttering anything at all. Bergvall’s flesh and bone thus become integrated with the regime of devices, interface and media – along with the more overtly technological microphone and tape player – shifting the line by which we distinguish the performing human from her prostheses; in effect, embedding this distinction within the body.

Performance is the ideal site for glitch interventions into language production, retrieving interfaces from the background at the moment they would usually disappear as ‘used’. Scourti’s recent performance Think You Know Me, 2015, at Transmediale plays the predictive text algorithm of her iPhone in a way which brings it back from just such a vanishing point. Scourti’s work explores what a ‘self’ is in a networked situation. Her innovation, in this and other works, is to overload the desire of the technological algorithms for ever-greater intimacy and complicity. As with Bergvall’s About Face, the resulting work brings into productive indeterminacy the boundary between the physical apparatus of human speaker and that of the technological device.

In preparation for Think You Know Me, Scourti linked the keyboard’s predictive function to her blog, Gmail, Facebook, Twitter and Evernote records, effectively producing a highly personal database on which the algorithm would draw – a function which is built into most smartphones with a view to generating supposedly accurate and personalised predictions. For the performance itself, she took to the stage and spoke a monologue as suggested to her live by the phone’s predictive text function, apparently allowing it to speak through her. Spoken as a public declaration, the overt identification with the device’s whims pushes the interplay between tool and user into a game without end. Word by word, Scourti’s enunciation through the phone, and the phone through her, appears to be on the verge of an intimate declaration, but this tension is undercut by an algorithmic insistence on the capacity of a phrase to continue: ‘You just want me to … want me to make more … more content … content intimate relationships in childhood … in childhood reproduce … reproduce social media marketing.’

This diminished attention span disclosed in the unending phrase-making of the device stutters and stammers at our ability to process it. Along with the self/device binary broken down by Scourti’s admission of the phone as her confidant and interlocutor, the word-units themselves have their edges blurred – each no longer a building block in a linear path towards a declaration but rather a node for any number of lines of flight into further positions inside the database of personal, professional, philosophical or even banal units.

Following a tradition established in Bergvall’s About Face, Scourti’s Think You Know Me discloses the techné of the speaking self as composed of a series of prostheses. The evolution in Scourti’s work comments on the nature of the ‘computational prostheses’ of new media. In fact, as both the prosthesis and Scourti herself share double billing, the performance takes the form of a frenetic double act wherein the profound, funny and moving moments take place at the point of translation: ‘everything will make sense of humour.’ ‘hello my name is on the way to get a free contact with you.’ ‘release yourself from bondage into the best of apple aftercare service.’ ‘the setting sun a skype wall between us.’ ‘statistically the best of the green and gold and blue and silver lining.’

Unlike Scourti’s speaking voice, the computational database is non-linear – and hosts no progression – and this spatiality works against the linearity of speech. Somehow the performance of Think You Know Me recalled politicians’ televised interviews: containing many words of apparent significance, phrases which gestured towards making a statement of some kind, but the cumulative effect being one of circularity and incoherence, no form suggesting itself. Each word-unit of Think You Know Me, then, performs an unsettling, and frequently funny, sleight of hand: it continually appears to make sense yet ultimately says nothing at all.

Precisely because they are engaged in the relation of doing and meaning, works engaging in new media’s computational prostheses – playing at the boundary of human and technological apparatus in the production of language – perform an additional tension between the computational terms algorithm and data. The code-poems of net artist Breeze offer a similar confusion in written form. In a series of works originally distributed en masse via mailserv networks, Breeze used a hybrid of code and natural language called Mezangelle, which undermines code’s necessity for precision with a spew of potential meanings nested within each word-unit. Here, language is obsessively interrogated for its inferences and indeterminacies, and is revealed as branching away from rather than leading towards singular meaning. In effect, the texts linger between unrunnable programs and unusable data: ‘Echo[y_lingers_in_mobile_tongues] Bravo[g(l)ued+gorgeous] [so_we]T[+not_much_dryness_t]ango [(brea)thing:u:in+flow:u:out(re)].’

Breeze’s codeworks are what Julia Kristeva describes as the abject – refusing, like Scourti’s and Bergvall’s co-authored utterances, a singular origin and instead flipping their affiliations between subject (author/data) and object (device/algorithm). There is a curious revulsion which accompanies the reading of Breeze and Scourti’s works in particular, which is located at the emerging horizon of the post-human, whereby the Cartesian mind-body dichotomy, which hitherto dominated our thinking around language, becomes complicated by the increasing complexity, proximity and form of computational prosthetics.

In a further evolution of this post-human exploration, Trecartin has placed a computationally frantic form of speech at the centre of his films. These dialogues consist of frenetic aphorisms sewn together into a continual spew which oscillates between meaning and pure action – what Trecartin describes as ‘accepting the flux of things rather than the definition or container’. The words speak themselves out of the characters’ mouths, the inhuman speed of their delivery pushing their relation to us to its limits. Here, speech is under command, suggesting some hidden force akin to the economist Adam Smith’s image of the ‘invisible hand of the markets’. The environment of these films is one where capital has exhausted the conscious and seeks to colonise the unstable unconscious realm beyond: the ‘Freudian slip’ becomes indistinguishable from the catchphrase; nonsense indistinguishable from the irruption of a new truth. In one section of his latest trilogy, Centre Jenny, 2013, a character sitting in a kind of technospiritual daze produces iterations on a single phrase: ‘You might end up in touch with the source. You might end up with in touch with the source.’ This minor grammatical slip – one among many in the film – becomes the subject of a highly productive indeterminacy. Is ‘in touch with the source’ something you are – ‘you might end up [being] in touch with the source’ – or, in this world, is it a commodity, as in ‘you might end up with InTouch-With-The-Source’? In the world of Centre Jenny, this phrase suggests, ownership and being – like human and techno-financial determination – are split along a flickering, indeterminate relation.

This theme is also at the centre of work by Jennet Thomas (Profile AM391), who notes that ‘pretty much all of my work touches on a kind of slippage of what should be metaphysical (or some kind of immaterial code) into the material’. This slippage between the metaphysical and the physical is the fullest extension of what I have termed glitch poetics, specifically prior to articulation. Thomas’s latest work, The Unspeakable Freedom Device, 2015, is a suite consisting of a film, exhibition and publication which deals extensively with the shifting and glitching of boundaries between human and technological language as our interface with the world. The characters in The Unspeakable Freedom Device relate to a world which recalls Derridian conceptions of language as forever partially withdrawn: its ‘collapsing signs and imploding meanings’ flickeringly apparent via the characters’ technical apparatus and media, but otherwise generally absorbed into the strangely bucolic surroundings. Throughout the film, what should be solely linguistic metaphors are taken beyond the metaphysical role of meaning and are frequently enacted on the body. This is perhaps most disturbingly reflected in the fate of the red ‘workers’ whose hands have literally withered and dropped off in the face of an unnamed ‘semiotic onslaught’: ‘their useless hands shamefully exposed to raw unfiltered awareness’.

It is this flickering relation between the linguistic and the material which the titular freedom device – or ‘Thatcher device’ in homage to its neoliberal connotations – proposes to do away with completely, as the salesman/politico Blue John proclaims in the closing scenes: ‘Eternal BLUE, beyond all fluctuations – Unspeakable Freedom!’ The device is the ultimate techno-linguistic app as computational prosthesis, producing in its user-hosts the phenomenon of being ‘free’ while ‘always working’, and thus enslaved to cognitive labour. In the finale, this device – a heartshaped hologram (uncannily anticipating Tony Blair’s recent exhortations to the left wing of the Labour membership to ‘get a heart transplant’) is simultaneously pitched as a commodity to be owned and revealed as that which has already been implemented.

Given the privileged role of indeterminacy in maintaining a balance between physical and linguistic realities in Thomas’s work, it is worth noting the lack of synchronicity between the ending of the video and the screenplay version of The Unspeakable Freedom Device. True to its linear form, the published screenplay seemingly reaches a definite end, even though this is signified by a ‘Restart’: ‘The Thatcher Device has worked its logic into everything, and soon the fine blue filaments of Restart begin to show. It’s more than a system. It’s the living end.’ The film, by contrast, is proposed as an infinite loop: a virtual-reality continuity error allowing the interior of a deserted manor house to interpose itself between the conference hall of the finale and the bucolic surroundings which open the film. By producing two endings, each specific to their medium, Thomas therefore suspends indefinitely the result of the showdown between red/green and blue – the colourfully attired antagonists in the film – making of the project itself an infinitely irresolvable ‘living end’. Thomas refuses to take a stand on whether this end is currently being lived or whether it is an end at all – precisely the infinite purgatorial suspension the words ‘living end’ imply.

The productive potential of such indeterminacies to hold us in the infinite horizon opened up by language could be the distinguishing mark of what I have described here as glitch poetics – and therefore also of what it is that language reveals of itself, hovering between us and the other. In this emerging field of media practice, at the frontier of language and technology, artists are extending what is sayable in order to articulate the formerly withdrawn but now increasingly coercive apparatuses which are involved in saying and in doing. By engaging with timeless questions about the interior self and exterior other in language, these artists are addressing increasingly insistent issues raised by computational prostheses.

Nathan Jones is a poet and cross-disciplinary researcher in English and media at Royal Holloway University of London.

First published in Art Monthly 392: Dec-Jan 15-16.