Feature

Health v Wealth

In the face of increasing privatisation in the UK Giulia Smith discusses the politics of health

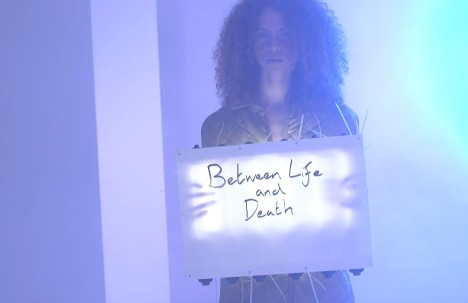

Oreet Ashery, Revisiting Genesis, 2016

Drawing on examples by artists and activists from Ilona Sagar and Johanna Hedva to Oreet Ashery, Simone Leigh and Alice Brooke, Giulia Smith looks at alternative practices and approaches to health issues.

What is health? This was the question behind the Pioneer Health Centre, a holistic experiment in preventive medicine set up in Peckham by Dr George Scott Williamson and Dr Innes Hope Pearse from 1926 to 1950, when Britain was moving towards, but did not yet have a national healthcare service. Initially run from a terraced house, in 1935 the ‘Peckham Experiment’, as it is more commonly known, moved into a bespoke modernist complex, which for a nominal membership fee offered local families (not individuals, it should be stressed) access to sports grounds, gardens, a swimming pool, childcare and recreational facilities, including a cafeteria and a theatre. Besides undergoing a yearly medical check-up, the families had few obligations. With the exception of ‘Keep Fit’, a course devised by the young mothers of Peckham, there were no organised classes or tailored training programmes. Williamson and Pearse believed that society should be entrusted with its own self-care. Their theory was that by simply modifying the environment, the community would spontaneously change for the better. The doctors also believed that being healthy meant much more than being disease-free. It meant access to communal space and decent housing. It meant shared crèches. It meant socialising, dancing, having a laugh.

For the past year, I have been working as the historian in residence on ‘The Peckham Experiment: A Centre for Self-Organisation’, a creative research project led by the Art Assassins (the South London Gallery’s group for 14-21 year-olds), with whom I have been exploring the archive of the Pioneer Health Centre in the Wellcome Library. Our conversations have often paused on the viability of such an experiment in our post-welfare present. Could we have something akin to the Pioneer Health Centre today? Or, better, why can’t we have it any more? Several artists were invited to explore these questions alongside the Art Assassins. Most recently, Ilona Sagar produced a short film about the centre titled Correspondence O, 2017, which Maria Walsh reviewed in an article for Art Monthly (AM415). ‘The difference between then and now’, Walsh pointed out, is that we have relinquished a ‘public-spirited holistic approach to health and community’ in favour of a neoliberal model premised on the individual management of mental and physical fitness. This is an altogether different version of self-care from that championed by Williamson and Pearse in the 1930s. The system we are faced with today is not only individualistic but effectively discriminatory, in that it is increasingly based on financial access. The conversion of the original Pioneer Health Centre building in Peckham into a gated compound is symptomatic of this shift. Whether we are talking about housing or healthcare, we are dealing with the total gentrification of people’s lives.

If the US provided the original paradigm for the privatisation of healthcare, clear-cut distinctions based on national context are increasingly difficult to make. In the UK, the NHS is being systematically defunded and outsourced in pursuit of austerity. Faced with this situation, it is imperative to stay with the question of what health can mean beyond money and statistics. Johanna Hedva, a Korean-American ‘writer-performer-witch’ living with chronic illness, recently tackled the subject in an epistolary essay titled ‘Letter to a Young Doctor’ published by Triple Canopy. The text purports to address the existential doubts of a (possibly fictional) junior physician called Erica, who is alleged to have contacted Hedva after coming across her 2016 online article, for Mask magazine, ‘Sick Woman Theory’. ‘You wrote me asking if I can think of a way, any way, that healing might happen within the current institution of the medical-industrial complex,’ Hedva begins, before admitting: ‘I find that none of us really knows what healing means.’ While insisting that we approach the task as an open question, Hedva also maintains that healing must necessarily be a political process, which can only start with seeking reparations for biopolitical traumas including colonialism, sexual exploitation, economic displacement and gentrification.

That ‘Letter to a Young Doctor’ was published in a special issue of Triple Canopy titled ‘Risk Pool’ (a reference to health-insurance protocols) points to the fact that the art world is becoming concerned with debates and practices that pivot on concepts such as health, healing and care, but have much broader political ramifications. In this article, I examine works by artists who have recently confronted the privatisation of health by taking the opposite approach. The examples I draw on all appeal to a collective subject, whether because they are performances that entail a participatory element or because they are scripts structured in a dialogic format. In this way, health itself is represented as a fundamentally relational field (however broken). Williamson and Scott believed that a healthy community was the product of a healthy environment. It follows that the opposite is true as well. For the most part, the artists featured in this article deal with the social consequences of a hostile environment. For Simone Leigh, as for Hedva, health is inseparable from racialised histories of economic and social disenfranchisement. Both engage with alternative medicine as a way of mobilising grassroots approaches to the therapeutic. Alice Brooke, an artist based in Glasgow, draws on witchcraft and herbalism for similar reasons. Her performances prompt reflections about privacy, institutional assimilation and the place of health activism in the art world. Oreet Ashery (Interview AM381), on the other hand, delves into a claustrophobic reality in which digital automation leaves little space for humane forms of contact between doctors, terminally ill patients and their loved ones. All of them interrogate what collective forms of care might be imagined beyond – or, even better, in spite of – neoliberalism.

In the past few years, Leigh has become known for creating socially engaged art projects devoted to promoting healing and agency among women of colour. Most recently, The Waiting Room, 2018, honoured the tragic but sadly not isolated fate of Esmin Elizabeth Green, a Jamaican woman who died unnoticed in the psychiatric emergency room of a New York hospital after waiting more than 24 hours for medical attention. The Waiting Room took place in the New Museum and followed directly from Leigh’s Free People’s Medical Clinic, 2014. Both projects tapped into a lineage of radical health activism promoting black self-determination, with sources ranging from the Black Panthers’ Free Clinics to The United Order of Tents, a clandestine order of African-American nurses active since the Civil War. In both cases, the main attraction was a calendar packed with what Leigh calls ‘care sessions’: health-related workshops ranging from lessons in Caribbean medicine to free HIV screenings.

A quick browse through the list of workshops on offer at the New Museum reveals an expansive and politicised approach to the questions of what healing is and where it needs to happen. Among the scheduled activities one finds, for example, a ‘Guided Meditation for Black Lives Matter’ and ‘Home Economics’, an outreach project only for black teenage girls – several events were closed to non-black people. According to Helen Molesworth in her article ‘Art is Medicine’ in the March issue of Artforum, some of The Waiting Room’s visitors only got to see an empty room with a display cabinet lined with glass jars filled with herbal concoctions. While the point was to recreate (for white visitors) the experience of frustrated anticipation implied by the exhibition’s title, secrecy and separatism are Leigh’s cardinal tactics, reflecting not only the chronic erasure and deferral of black subjects, but also their capacity to self-organise and go underground.

The work of Glasgow-based artist Alice Brooke also contends with the dangers of exposure. For Stripping, 2017, a performance taking place at Hotel Ozone in Prague, Brooke picked a bunch of mugwort stems from the wastelands of the Czech capital and positioned them in the centre of the gallery. The artist then invited the audience to sit in a circle and participate in a ‘grounding meditation’ based on a script by Starhawk – the neo-pagan witch-activist who in the 1970s pioneered the Goddess movement (which, it should be said, was a largely West Coast phenomenon, criticised by many, including the artist Ana Mendieta, for its universalising and white-centric assumptions).

There is a long lineage of eco-feminist and queer activist artists who have embraced ‘radical herbalism’ as an alternative to the medical-industrial complex and a critique of dominant forms of techno-scientific knowledge. Examples include Faith Wilding, whose drawings of botanical and human-animal assemblages were on display earlier this year at Res. in London as part of an exhibition titled ‘Alembic I: Mystic Body’. The practice of foraging and the ideal of the commons feature prominently in this tradition, pointing towards a critique of the gentrification of all realms of experience, from housing to eating to healing itself. Brooke’s performance Stripping relates to this lineage. What is more interesting, however, is how the artist chose to document the event on video – or, rather, to not document it, for Brooke deliberately positioned the camera so that it would only focus on a mugwort shoot positioned right in front of the lens, with the rest of the room melting into an indistinct blur. While the title, Stripping, refers to the act of stripping and getting to know the layers of the plant, it is also a tease.

Most artists would think that making their work hard to see is tantamount to professional self-sabotage. For Brooke, who like Leigh is a health activist, it’s a conscious political choice. The artist is part of a collective of herbalists and grassroots campaigners who run a free clinic for asylum seekers with increasingly restricted access to the NHS. The collective does not claim to be curative in the clinical sense, but aspires to be therapeutic on a social and psycho-political level. Brooke is understandably weary of the art world’s co-option of ‘the politics of care’ and remains adamant about keeping her activist projects away from the limelight (despite pressure from curators). Today, then, remaining invisible is a political strategy that may have as much to do with rebuking white entitlement as with resisting being consumed by the art world.

The problem is that art institutions are dependent on proving that they can meet public engagement targets for financial survival. In the UK, museums are caught in a budgetary purgatory whereby state funding has been drastically cut and no tradition of tax-incentivised philanthropy exists to replace it. This creates a vacuum that can be exploited to push art into performing instrumental actions whose ‘utility’ translates into scientifically measurable outputs. Under the past three Tory governments, national funding bodies have invested in creative projects that claim to bring technological innovations and health benefits to their audiences (also known as the STEAM remit, as in STEM subjects – science, technology, engineering, mathematics – with art in the middle). Arts Council England, for example, is actively calling for ‘arts interventions in healthcare and general wellbeing’ (see ACE’s blog post ‘Feeling Good’). There is nothing inherently wrong with this, just as in principle there is no reason to disagree with the rationale, cited on ACE’s website, that ‘good health and well-being are reliant on all kinds of factors, not just physical, but also psychological and social’, meaning that art has a big role to play in the well-being of communities. What is disturbing, however, is that artists and cultural institutions are being encouraged to step in where the state is withdrawing.

While claiming autonomous spaces of healing for small and often disenfranchised communities, artistic practices such as Leigh’s and Brooke’s are caught in a double bind, in the sense that they can never completely escape the neoliberal framework in which health is increasingly delegated to patients. To some extent, herbalism epitomises this contradiction. If it can be radical, herbal medicine also plays a prominent role in the highly profitable market for preventive self-care (one word: spirulina). The line between an empowered patient and a patient whose chief resource is purchasing power is a fine one. Jasbir K Puar refers to this system as ‘the economics of debility’. The field of debility studies is aligned with political efforts to challenge the binary discourse of dis/ability by highlighting how nobody consistently experiences optimal conditions of health. Over the past few years, its central tenets have gained ground among contemporary artists and theorists, including Hedva, who prefer to talk about healing rather than healthiness. According to Puar in her 2012 article ‘Coda. The Cost of Getting Better: Suicide, Sensation, Switchpoints’ for GLQ A journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, debility is the depletion of all bodies, but especially marginalised ones, under neoliberalism. If everyone is more or less debilitated a lot of the time, it follows that no one is ever truly ‘able’. The same economic system that drains us, Puar maintains, also profits from stoking our anxieties about being sufficiently ‘fit’. As the market for DIY therapy expands, health becomes a highly fetishised commodity and something of an unattainable mirage. Those who can afford it invest in constantly evolving regimes of therapeutic self-maintenance. Their quest for total bodily recovery is bound to be forever frustrated, however; health, if it exists at all, can never be final.

Nor can death, according to Ashery’s Revisiting Genesis, 2017. The piece, which recently won the Jarman Award, is an open-access video performance in 12 acts, each one a dark play on the seemingly absurd, yet evidently lucrative, machinations of the digital afterlife industry (which is available to watch at revisitinggenesis.net). Although the story pivots on the fatal illness of a character named Genesis, there is no linear plot to speak of. Even within a single episode, dialogues are cut midway through, voices echo, and the camera moves in and out of focus. This disconnected structure reflects and enhances the alienating rhetoric of the online death industry, whose callous offers range from barcode-activated gravestones to creepy AI avatars programmed to replace you on social media. It sounds like sci-fi but it is not – it’s what companies like Facebook and myriad other businesses with inane names like ‘Dead Social’ are investing in.

While exploring the digitisation of death, Revisiting Genesis is also a commentary on the automation of life at its most defenceless. The opening scene features a group of friends who are trying, unsuccessfully, to get answers and medical advice from an automated phone service. The dialogue is patently abstract and so is the blank space the actors are standing in. That the situation is preposterous does not mean that it isn’t realistic, however. Who hasn’t felt numb and furiously alone when trying to get through to a human operator? Many worry that this is going to be the future of all doctor-patient relations, especially now that we are encouraged to seek treatment through smartphone apps. Revisiting Genesis taps into these anxieties, condensing them into a sequence of awkward vignettes that make for painful but absolutely worthwhile viewing.

As strange as it may sound, Revisiting Genesis takes me back to the Peckham Experiment, and the idea that health is first and foremost about social relations (perhaps a social relation, even). The different episodes in the series add up to a web of associations linking experiences of debility with anything from friendship to art and gentrification. In this way, Ashery expands the meaning of illness well beyond the body of the individual. Although every act is infused with a sense of distance and disaffection, the play as a whole is fundamentally dialogic. In it, a cast of characters that includes some of Ashery’s friends, a group of professional actors, real patients living with severe illnesses, a GP and a number of nurses engage in both scripted and genuine conversations about care, death and digital legacy.

In what is perhaps the most powerful chapter in the series, four nurses (two acting, two presumably genuine NHS staff) discuss the importance of talking and listening to each other and to their patients when dealing with death IRL – ‘in real life’. ‘I realise I don’t do this enough,’ one of them says, ‘being able to just talk about how I feel.’ This intimate confession is in stark contrast to the artificially friendly tone of the online care industry. Just as Hedva’s tentative message to a young physician, the ninth episode in Revisiting Genesis entertains the possibility of healing through social contact, offering an image of what must be safeguarded and cultivated in the future. ‘The most anti-capitalist protest is to care for another and to care for yourself,’ Hedva maintains. ‘To protect each other, to enact and practice community.’ The different artists examined in this article try to do so, in spite of everything, including the art world.

Giulia Smith is an art historian based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 418: Jul-Aug 2018.