Feature

It Was What It Was: Modern Ruins

Gilda Williams on the politics and aesthetics of ruins

If there is a difference between derelict buildings and ruins, could the distinction relate to the oppressive systematisation inherent in modernist architecture? And how have artists explored the difference between the two terms?

A word close to ‘ruin’ is ‘derelict’, yet these two terms prompt opposite reactions – a ruin inspiring poetry, the other calling for demolition. What exactly is the difference between them? London is host to a thriving sub-city of derelict architectures – abandoned pubs, boarded terraces, trails of vacated shops – but, arguably, few real ruins. Go to www.battersea-powerstation.com to see how one of London’s most impressive and last remaining industrial ruins is on the verge of reclamation, to be swamped by the usual crop of high-rise residential blocks. Watch the words ‘Pruitt’ and ‘Igoe’ form as if by magic before your very eyes. The demolition on 16 March 1972 of the doomed Pruitt-Igoe residential towers of St Louis – whose dark, deserted, concrete ‘streets in the sky’ proved an ideal hunting ground for a flourishing community of muggers – was claimed by postmodernist architectural historian Charles Jencks as ‘the day modernism died’.

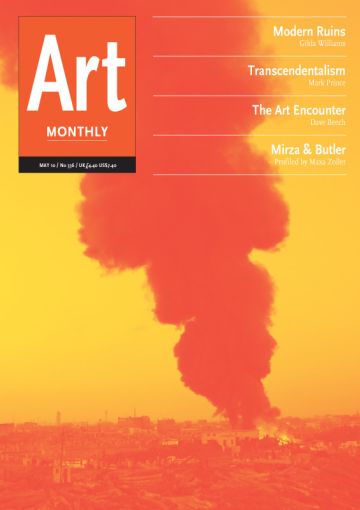

Weirdly, the successive era, our contemporary period, probably also began with a ruin: the collapse of the Twin Towers in 2001, which ushered in a whole new (and still unresolved) world order. Weirder still, both Pruitt-Igoe and the Twin Towers were built by the same architect, Minoru Yamasaki, giving him the dubious title of the most significant architect of cataclysmic ruins of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. He died in 1986, and was thus spared having to watch, for the second time, another of his architectural achievements spectacularly razed to the ground. We might, however, keep an eye on his other, still-standing edifices (for example, King Fahad International Airport in Saudi Arabia) in case another should perish and take the rest of the world down with it.

For almost two decades after it closed as a power station in 1981, Bankside stood like a ruin on London’s Southbank, eventually to be reborn in 2000 as a testament to the unexpected mass appeal of modern art. Art and ruins have entered into a close alliance, with artists regularly called in to ‘do something’ with unused yet still viable places that nobody else seems either foolhardy or imaginative enough to cope with. Back in the recession of the early 1990s, in ‘Project Unité’ curator Yves Aupetitallot invited artists including Jim Isermann, Philippe Parreno and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster to ‘do something’ with Le Corbusier’s crumbling masterwork, Unité d’Habitation, near Marseilles. At the time, Le Corbusier’s 12-storey social experiment stood half-empty; now it boasts a thriving community of modernist aficionados. In the summer of 2009, New York City’s vacated Governor’s Island, a former military site abandoned in 1995, hosted ‘This World & Nearer Ones’ curated by Mark Beasley and featuring 32 international artists (Reviews AM329); can the developers be far behind? On this site heading towards ruin, Teresa Margolles imported another ruin: Shot-Up Wall, 2008, a segment of cinderblock wall scarred with bullet holes and flecks of blood – the actual backdrop for a gang execution in the artist’s home city of Culiacán, Mexico. In a work that is, one could say, the deserted ruin of the wall behind The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, 1868-69, after Manet’s exquisitely painted firing squad has gone home and the heap of bodies cleaned up, Margolles’ brief length of wall returns us to one of Romanticism’s most beloved paradoxes: as a fragment, a ruin is more loaded with meaning than when it was part of a whole.

Artists have traditionally demonstrated a remarkable willingness to live and work inside ruins too. Artist in squats like those at Tacheles in Berlin and RAMPart in London save urban architecture from decay only to face eviction or, as Svetlana Boym describes Tacheles residents, to be reduced to playing bohemian extras in semi-dilapidated neighbourhoods ‘where Bavarian bus tours stop for a taste of exotic Berlin radicalism’. Artists have been upgrading peripheral London squalor into profitable building stock since at least the days when Constable moved to the then-semi-rural, now-posh area of Hampstead, or the yBas colonised Hoxton. But in our current, exponential world population boom, estimated to hit 8bn by 2025 – that’s twice as many people as inhabited the earth in 1974 – where are artists leading us? Wherever there’s space. For example, beneath bridges, like the one where Ian Davenport’s colourful Poured Lines, 2006, now makes the grey underbelly of the Western Bridge in Southwark more hos-pitable. Or we may follow Conrad Shawcross’s Chord, 2009 – his complex, rainbow-like rope-weaving machine – underground, into an abandoned railway line complete with shreds of Second World War-era travel posters (actually 1990s-era copies, pasted up during a filmshoot) and situated in the heart of London where aboveground office rentals start at £40/sqft. Ruins have always been replete with nostalgia; how much more so in the 21st century, when cities like London just can’t afford them? In future, real ruins may be replaced only by their memory. Albert Speer lamented that European modern architecture would produce deeply disappointing ruins; in fact we seem destined to produce few locally at all, just endless lost ruins.

Invisible ruins are the subject of Mona Vatamanu & Florin Tudor’s Vacaresti, 2006, in which the Romanian artist Tudor traces with sticks, wire and string the outlines of the once magnificent 18th-century Vacaresti monastery outside Bucharest, which Ceaucescu demolished in 1985. Tudor’s performance – as he walks in straight lines, abruptly turning corners, across a barren field – is a ‘nonument’ to a mistreated, absent ruin. In Kant Walks, 2005, Danish artist Joachim Koester retraces the legendary strolls of the philosopher through his beloved Königsberg, renamed Kaliningrad by the Soviets in 1945 after the Nazis had burned down the synagogues and RAF bombs had flattened most of the old town. Koester drifts through Kantian psychogeographies in this unrecognisable city, surrounded by battered Pruitt-Igoe-like towerblocks and the vast and crumbling communist cultural centre, built in 1970 over the ruins of the former Königsberg castle and hopelessly sinking into the castle’s former dungeons: one doomed ideology replaced by another.

Ever since Italian Renaissance writers fantasised about reviving the glories of Ancient Rome evidenced in their grand and broken antiquities, ruins have been put to work for politico-cultural causes. In summer 2009, the New York Times ran a lengthy piece titled ‘Ruins of the Second Gilded Age’, a cautionary visual essay on the greed and waste of the collapsed US building industry. Featuring splendid colour photographs by Portuguese photographer Edgar Martins of unfinished homes and abandoned building sites, the article revealed a generation of 21st-century US ghost towns, lost in capitalist limbo between boom-town prosperity and quiet devastation. It turned out, to the dismay of some, that the photographs had been digitally altered to enhance their sense of emptiness and drama, resulting in (semi-)artificial ruins constructed via the miracles of Photoshop. Nothing new there; Martins, like his Romantic counterparts over 200 years ago, had adopted artificial ruins for aesthetic pleasure but also to drive home a political point. In the same way, late 18th-century English architects of false ruins were commissioned to erect fragments of monasteries and medieval castles in pleasure gardens not only for their beauty, but also because their patrons delighted in seeing the outmoded institutions behind these half-buildings – the papacy and feudal aristocracy – in visible collapse. The artificial ruins announced to visitors their owners’ liberal politics – not unlike the LibDem sticker in your neighbour’s front window.

Robert Kusmirowski’s Bunker, 2009, is another artificial ruin: a reconstructed Second World War bolt-hole staged in fetishistic detail (built by a professional forger and artist) that points to a longing for both old-fashioned war and future apocalypse, though without the visionary exuberance of Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s TH.2058 commissioned for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2008. Her mass sleeping quarters, stocked and ready for emergency action in a future London evidently on the verge of catastrophe, seemed to return Bankside to the empty, bunker-like ruin it once was, erasing its brief history as a museum and visualising Benjamin’s idea of ruins as offering a ‘prophetic’ picture, one in which ‘all that lies in store for us has become the past’. This before-and-after effect performed by ruins was also apparent in Jeremy Deller’s It Is What It Is: Conversations about Iraq of 2009. Here, after a series of talks on the Iraq experience held at New York’s New Museum, Deller went on a road show across the US with two vehicles: a massive, top-of-the-line, shining RV ‘Chalet’; and the husk of a rusted and crumpled, bombed-out car exported from Baghdad. Here, Deller updates one of Pop Art’s most treasured subjects, the American automobile, by parading before ambivalent citizens the before-and-after effects of US excess and its petrol-reliant romance with the open road.

A ruin is said to result from some man-made or natural disaster – an earthquake in Lisbon; reformationist zeal in St Andrews; a dioxin spill in an abandoned town in Ohio. So much human failure and misery from the recent past is tied up with ruins: postwar Hiroshima, post-meltdown Chernobyl, post-communist Eastern Bloc, post-Katrina New Orleans. The remains of Berlin in 1945, or Detroit and Beirut today. Which exactly is the calamity that has determined contemporary artists’ interest in ruins? The simple answer would be the collapse of modernist ideals, and the nagging sensation that it was all just an elaborate, late-Enlightenment folly whose optimism, moreover, we have lost forever. This was literally staged in Philosophy of Time Travel, 2007, an installation by Edgar Arceneaux, Rodney McMillian and others at Harlem’s Studio Museum, wherein Brancusi’s Endless Column, 1938, lay in ruins, having finally reached its announced end and, toppling under the weight of its own sky-high ambitions, crashed through the roof. In Cyprien Gaillard’s Belief in the Age of Disbelief, 2005, the artist presented Le Corbusier’s Unité flourishing in an arcadia of greenery; in fact this is just how the architect first imagined it, surrounded by bois de Boulogne-type overgrowth and not the stubble of ugly lowrise housing surrounding the Marseillian monument today – hinting at the closet Romantic Le Corbusier actually was. Postmodernist architectural theorist Colin Rowe surmised that the carefree, perfectly contented beings whom Le Corbusier drew occupying his clean sparse flats and tending his jungle-like balcony gardens were just the modernist equivalents of the Romantics’ noble savage: want-free beings relocated in idealised forest homes in the sky (the same ideological creatures recently seen, 10ft tall and tinted blue, in James Cameron’s Avatar, 2009).

The parallel between the state of the house and the state of the inhabitants’ frame of mind has been the leitmotif of so many gothic tales centring on ruins, from Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher, 1839, to Grey Gardens, 1975, Albert and David Maysles’s documentary of the long-declined highsociety Beale family (socialite mother Edie and daughter Edith, relatives of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis) who live in a spectacularly dilapidated villa on Long Island’s southern Gold Coast, the fading backdrop for the pairs’ own mental deterioration. In Ulla von Brandenburg’s Singspiel, 2009, filmed in Le Corbusier’s single-family masterpiece Villa Savoye outside Paris, built in 1931, the now-abandoned home becomes a set for family melodrama. To populate Villa Savoye with a singing and performing family is to contradict its very spirit; theatricality and Modernism do not mix, as Michael Fried once emphatically made clear. Vintage photographs of the house never show any human residents, who probably would have looked gaudy and out of place there. Apparently the house began falling into ruin almost immediately; the victim of experimental building techniques, Villa Savoye was shabbily built, leaky and poorly insulated. According to von Brandenburg, the Savoye family was not happy there. A tense, eight-year correspondence between Madame Savoye and the architect sees her endlessly complaining about the detrimental effects that the cold house is having on her frail young son, whose pneumonial condition was made worse by the draughty architectural masterpiece. Le Corbusier eventually grows impatient – what is one child’s health in the face of the world’s finest architecture? The villa was eventually abandoned in the 1940s and virtually ignored until around 1963, when Corbusier himself insisted on its preservation. If we can finally define a ruin as an architectural site whose inhabitants were forced out, whereas a derelict is a place so unwelcoming its residents packed up and left voluntarily, Villa Savoye, one of the 20th century’s purest and most emblematic architectures, was by this definition just another common derelict, not a ruin.

For Georg Simmel, writing in 1905, a ruin is a site where nature and humankind work together to form a collaborative work, a vision evoked in Robert Smithson’s lecture/performance Hotel Palenque, 1973. There the artist verbalised humankind’s side of Simmel’s bargain by reading grand architectural efforts into this modest, abandoned cinderblock shell. In Smithson’s words and 43 35mm slides, the hotel is forever preserved, re-born as legendary jungle shrine to some Aztec god of entropy. Shifting in tone throughout – from satirist to poet, explorer, dumb American tourist – Smithson effectively follows in the footsteps of the many novelists and dreamers who, since the dawn of modernity, envisioned a depopulated world reclaimed to beauty by nature. From Mary Shelley’s The Last Man of 1826 to Richard Jeffries’s After London: or, Wild England of 1886 to JG Ballard’s The Ultimate City of 1978, artists and writers have fantasised about the entirety of humankind perishing by some happy magic, leaving our cities to collapse into what Benjamin called ‘irresistible decay’. William Morris, remembering with fondness the imagined end of London described by Jeffries, wrote of the ‘absurd hopes that curled around my heart’ as he read of the imagined cataclysmic end of the city. Why was Morris so comforted by the possibility of mass extermination? How can mankind, as Benjamin once asked, ‘experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order’?

Of course, any problem plaguing humankind – war, global warming, economic instability, unrequited love, thinning hair – would be miraculously washed away under a powerful carpet of weed vegetation, wild dogs and spectacular rodents. In Dead Cities, 2005, Mike Davis updates Jeffries’s 19th-century vision based on the evidence presented in New Scientist in 1996, which set out to describe, with scientific accuracy, how long it would take for all traces of mankind to be swept away once nature got the upper hand. The answer: 500 years – tops – with almost everything disappearing in well under a hundred. How pleasing to imagine kestrels and red-tailed kites occupying the immense owlery of Canary Wharf, all its windows long blown out and towering over a forest of buddleia, an imported plant to the UK so rapacious it penetrates into mortar to extract its moisture and is able to grow out of rooftops, pavements and empty swimming pools. The return to nature in the evacuated city of Pripyat, Ukraine, adjacent to Chernobyl, has been even hastier than scientists predicted; in 25 short years the city has been almost fully reclaimed. The football pitch, for example, is now a thriving little oval-shaped forest, flanked by decrepit bleachers: a mysterious ruin where a lonely visitor might sit and watch it grow.

Gilda Williams is a writer and lecturer at Goldsmiths College, London.

First published in Art Monthly 336: May 2010.