Review

Jitish Kallat: Covering Letter • Tangled Hierarchy

Adam Heardman on Jitish Kallat’s installation and curated exhibition confronting colonialism

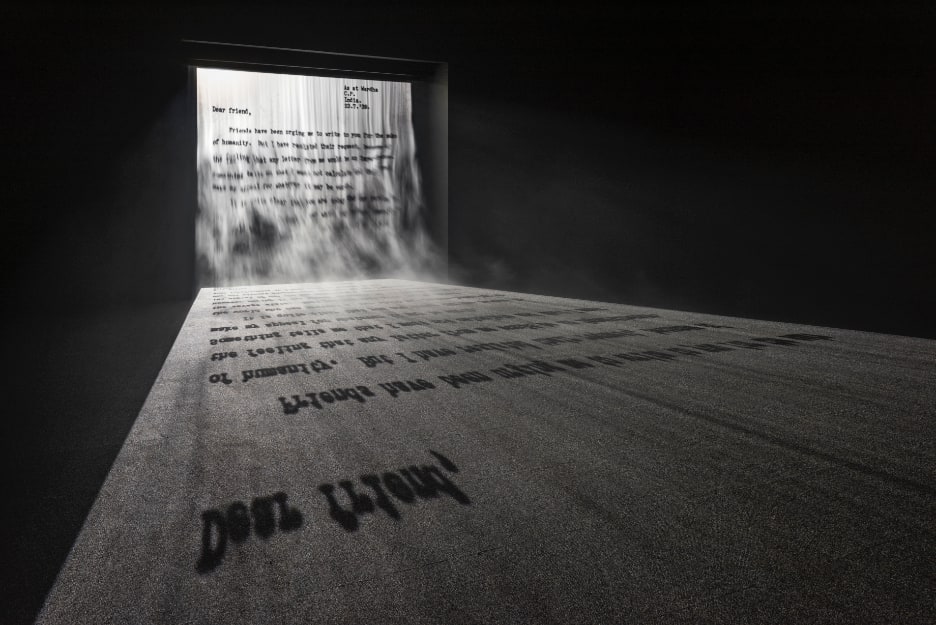

Jitish Kallat, Covering Letter, 2012

‘Dear Friend,’ the letter begins. ‘Friends have been urging me to write to you for the sake of humanity.’ In a vast, darkened room on the ground floor of the John Hansard Gallery, these words scroll upwards, projected onto a sheet of fog which descends in streams from the top of an archway and evaporates continually before reaching the floor. The backlit projection shines partially through the translucent mist so that the words also appear to move outwards into the room along the ground. Viewers can walk under the arch so that they pass through the curtain of vapour and the disappearing words. As the lines proceed, it is revealed that this is a last-minute appeal against imminent war, written on July 23rd, 1939, by Mahatma Gandhi to one Herr Hitler.

The artwork, Jitish Kallat’s Covering Letter, 2012, has a threefold power. Treating Gandhi’s letter like an exhibit allows us the relatively objective clarity of hindsight. We know what’s coming next, and this feeling of inevitability heightens the sense of tragedy. Secondly, this doomed injunction to peace, disappearing in front of our eyes, compels us to consider what similar opportunities to avert catastrophe might be vanishing with each passing present moment. Thirdly, the fact that the projected words seem to engulf us in the room (and even more so as we walk through the arch) communicates to us our complicity in the cycles of historical violence. The work lays history at our feet, moves it towards us until we are inside it.

Reminding the British art-going public of their complicity is key, here. Kallat calls the letter an ‘unlikely piece of historical correspondence’ and ‘a covering letter to an endless resume of world violence’. But Gandhi wrote to Hitler more than once, and certainly did not think of German Nazism as the earliest entry in the world’s CV of violence. In a letter to the same correspondent just over a year later, Gandhi was quite clear about which oppressive foreign power was of the greatest concern to India. ‘We resist British Imperialism no less than Nazism,’ he wrote to the Führer in December 1940. ‘If there is a difference, it is in degree. One-fifth of the human race has been brought under the British heel by means that will not bear scrutiny.’

Hitler’s industrial genocide was in part enabled by the velleities and collaborations of certain European nations who harboured anti-Semitic prejudices of their own, and openly inspired by the colonial machines of others, the UK included. Kallat’s invocation of Gandhi, and the immersive address of the artwork, calls our attention to these complex realities at a time when they are once again tragically pertinent. Parallels with the well-documented evils of contemporary Russia are obvious, but Kallat’s work also urges consideration of other malevolent regimes, from Modi to Netanyahu, as well as self-scrutiny about the proxy wars and arms trades perpetuated by NATO member states.

Alongside the film, Kallat has curated a new exhibition, ‘Tangled Hierarchy’, further exploring themes of power, historical cycles of violence, and generational or inherited traumas. As you ascend the gallery stairs to enter the show, motion-sensors trigger The Shepard Scale, an auditory illusion designed by professor Roger Shepard in which a musical note appears to be forever rising and falling without ever changing in tone. Nearby are several original sketches of Roger Penrose’s Impossible Stairs, 1950, which play the same trick of forever appearing to ascend/descend without actually doing so. It’s clear that we’re being asked to acknowledge the slipperiness of our perception, the arbitrary nature of the hierarchies by which we live.

When Lord Mountbatten visited India to discuss partition, exactly 75 years before this exhibition’s 2 June launch, Gandhi was observing a vow of silence. He communicated instead by writing down responses on scrap envelopes. Here, the central room is divided by a vitrine containing these handwritten notes, a powerful meditation on silence and severance which sets the tone for the rest of the room.

Zarina’s woodcut prints, Atlas of My World, 2001, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs from Partition camps and Mona Hatoum’s sculptures communicate the human costs of colonial geographies. Nearby, Kallat has included two refugee luggage trunks loaned from the Partition Museum in Amritsar, physical artefacts compelled to cross the newly formed Indian-Pakistani border in 1947. Hatoum’s huge hanging-glass map of the world, the transparent countries continually shifting their positions, reveals to us the arbitrariness of borders and the fragility of our home.

In the context of a UK gallery, the exhibition’s subject matter could appear to be a distant, abstract, historical concern, and, indeed, as with Covering Letter, ‘Tangled Hierarchy’ does allow for the critical distance of a historicised vantage. Yet perhaps the exhibition’s greatest triumph is that it also successfully locates historical trauma within the body, and begins to take an active role in healing these traumas.

Alexa Wright’s photographic series ‘After Image’, 1997, introduces the ‘phantom limb’ phenomenon. She photographs amputees and gives their testaments about the remaining sensations in their now-absent limbs. Nearby, Kallat has placed a re-creation of neuroscientist Doctor Vilayanur S Ramachandran’s pioneering Mirror Box, used in therapeutic treatment of phantom limb pain. Visitors are invited to place their hand in the box and feel the unsettling effects of cognitive and physical dissonance. This allows us to physically appreciate the questions of partition and pain raised by the artworks, tangibly imprinting these themes on the brain and body.

The exhibition concludes with Kader Attia’s truly remarkable film Reflecting Memory, 2016 (Interview AM448). It compiles interviews with neurosurgeons, psychoanalysts and academics interspersed with long shots of amputees interacting with mirrors. The film uncovers some astonishing truths. We learn, for example, that phantom limb symptoms are far more prevalent in victims whose injuries were a result of violence rather than accidents. The harder it is for the brain to consciously revisit the incident, the less the body is able to accept and recover from its loss. These patterns, it turns out, are written into psychological traumas like grief, and also dictate how societal oppression impacts people over generations. The tensed muscle memory of fear, shame and anger felt by a victim of racial profiling by a police officer physically recurs in future meetings with the police. It can be psychologically proven that oppressors pass on their internalised guilt through generations just as the oppressed pass on their pain. ‘Time alone doesn’t heal traumas,’ says one of the psychoanalysts. Instead, as with the mirror-treatment of phantom limbs, it’s a matter of consciously training the brain to acknowledge the ghosts that live within and alongside us so we can learn to release them.

The exhibition’s revelations are more factual than aesthetic. This is not a show particularly interested in moving you through traditionally artistic means. But it stakes a radical claim for contemporary art’s active role in not only diagnosing and meditating upon history’s greatest sicknesses, but also revealing new modes of thought and communication through which they might begin to be healed.

‘Jitish Kallat: Covering Letter’ and ‘Tangled Hierarchy’, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton 2 June to 10 September 2022

Adam Heardman is a poet and writer based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 458: Jul-Aug 2022.