Interview

Cover Stories

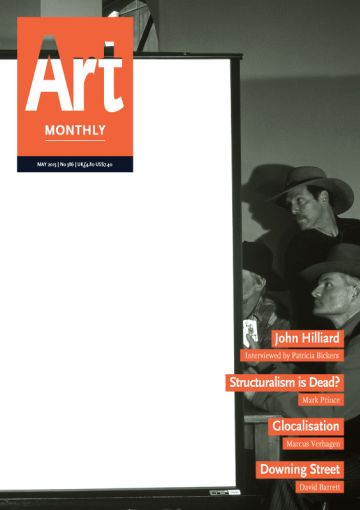

John Hilliard interviewed by Patricia Bickers

Patricia Bickers: One of the themes of your recent show at the Richard Saltoun Gallery was the recurrence of certain ideas in your work over the years. I wanted to start by asking you about new work – at least new to me – using digital technology: the ‘post-scription’ pieces. You talk in your own essay in the catalogue about an article you once wrote concerning the role of pre-scriptive drawing in your practice. What is the relationship between the two?

John Hilliard: Pre-scription means, in this case, a prescriptive drawing. It may sound a bit odd, but it’s the way I always work with photography. I effectively draw, or sketch out, or make a diagram for a photographic image before it ever exists, before I even take up a camera – so that’s always a preliminary stage for me. The post-scription, instead of being a drawing for a photograph, is a drawing from a photograph. There is quite a history of artists doing that, going right back to the 19th century, but I think the difference, in this case, is that rather than being a transcription of a work by somebody else, it’s a transcription of my own work. Part of the intent, initially, was to make up for a perceived lack that I see in photography – a lack of a particular kind of definition that you get in painting and drawing. It is something, if you like, very tangible, something that you might see in painting as brushstrokes or in drawing as a line – in the case of a lot of Renaissance painting, the drawn line is a feature, particularly where hands or faces are being described. Photography, normally, is a much smoother medium without that particular kind of definition – so, I was trying to import some of those properties that I value in other two-dimensional media.

PB: You have described the process succinctly as ‘a photograph of a drawing of a photograph from a drawing’. As in all your work, you constantly remind the viewer of these processes or stages in the making of the work, forcing the viewers to think about these processes and not to accept the surface as a smooth – to use your word – given.

JH: It is a kind of modernist inheritance, really. Whatever medium you use, one of your tasks is to engage with the medium itself and to articulate it on its own terms. Having decided very early on – in the latter part of the 1960s – that the photographs I took of my own sculpture would, in some way, displace it, so that photography would become the primary form at that point, part of my obligation was to discover and draw attention to the medium of photography itself – which is what I have done subsequently. Part of what I do is also a kind of critique of photography as it performs to represent things in the world. It’s a mixture of those two things, I think – having some kind of critical appraisal of that function, but at the same time having a sort of positive embrace of all the properties of photography.

PB: Yet you have always expressed a certain necessary ambivalence towards photography. You often return to this as a theme in your work. One of my favourite early works that was included in the show is Seven Representations Of White from 1972. It poses both a painterly question and a question about colour perception, but presumably it also addresses photography’s unreliability in respect of representation.

JH: I think it is a mixture of unreliability and specificity. One of my favourite quotes is from Jean-Luc Godard, speaking about film: that what is important isn’t the representation of reality, but the reality of representations. I am always very aware of that. Whatever your purpose, it is what you end up with – and the reality of that – that is important. That is what one has to deal with.

PB: In your notes in the catalogue you say that you described your early sculpture as being about ‘presentation’ rather than ‘representation’ and that, in a way, is what you are doing with photography.

JH: I think it is partly what I’m doing. It’s always problematic because however much you wrestle with what I think of as the problem of the image, it is also something very seductive. I think the word ‘ambivalent’ is the right word to use in terms of my own position. I’m seduced by the medium I use, but at the same time I have some critical distance from it. Between those two seemingly opposite positions is where I function.

PB: In the selection of works for the show there was much emphasis on your use of abstraction, in particular your use of what you have described as ‘evacuated zones’. But these voids are also an interruption – the action, to use a movie term, appears only on the periphery. That is a kind of refusal of the seduction of photography, a refusal to allow the viewer to entertain the illusion of entering the image space. At the same time you could be said to fill the void by reference to other media: to painting (the blank canvas in Debate (18% Reflectance), 1996), to cinema (the empty screen in Off Screen, 1999, or the curtain in Main Feature, 1995), or mirrors. But in every case, by interposing this flat plane between the viewer and the work, you stop the viewer from crossing the proscenium, so to speak – though there is nothing to stop viewers from projecting their own ideas onto them.

JH: Well, as I said, I think it betrays a continuing modernist sensibility on my part. At the same time that one is drawn into, let’s say, some kind of narrative or some kind of illusory space, one also has an enforced conscious awareness of the means of production and of the presence of the medium itself. It is a mixture of those two things. Like a lot of artists, I am trying to have my cake and eat it. I am trying to have the best of those two worlds.

PB: Your work puts a lot of responsibility on the viewer. It is possible, of course, to engage with it on the surface level – literally, since at one level the works are about surface – but if you choose to take the time to unpack the work, it will deliver a great deal more and result in a more equal relationship between the artist and the viewer.

JH: Those particular pieces that you are talking about are part of a body of work – whatever its antecedents in much earlier work of my own – from, let’s say, 1994 until about 2000. They were intended to be quite aggressive towards the spectator, I think, and even towards the medium itself. They were intended as a refusal, at least in large part, of photography’s conventional illusionism – so, in that respect, they might be an affront to the spectator. But if they also make the spectator do some work, I think that’s a good thing.

PB: Speaking of ‘affront’, one of the most aggressive works from this period that was included in the show is Study For Miss Tracy of 1994. The work is highly problematical in the same way that Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés is. In both works a woman lies spread-eagled on her back, legs apart, in a pose suggestive of rape. In this instance the image of the woman is overlaid by another, which is blurred and out of focus, so that the violence suggested around the edge is not confirmed by the superimposed photograph.

JH: I’d say the aggression is actually not towards the woman in the image. I think the aggression is towards the convention of pornographic or even simply erotic images because what it refuses to deliver is what someone might most like to access, which is the unadorned view of the model herself and that’s exactly what you cannot access.

PB: When you address these kinds of issues, you are walking a very difficult line, obviously.

JH: When I first started making images which were potentially provocative in the 1980s it was partly because, having worked my way through a lot of the facets of the medium of photography to do with picture editing or choice of film stock or choice of camera settings and so on, I began to think also about the subjects of photography and among those subjects are areas like the pornographic, the erotic, things like war photography and so on – images of sights which might not otherwise be easily available to us that we have some desire to have access to. I felt I wanted to have a look at that territory because it was there; because it seemed as much a part of the medium as anything else and, if you like, I wanted to dismantle it.

PB: Do you think that in Balance Of Power (3), a work of 2010, you were in part redressing that imbalance in that the Three Graces – the three nudes in the photograph – confront the male photographer in an image that is made up of more than one exposure, more than one ‘take’?

JH: There are two exposures from two exactly opposing points of view. It is an image which has no right way or wrong way up. It can be right way up or wrong way up depending on what you decide – but the normal relationship between the photographer and the models is intended to be subverted. All the models are in the process of rebelling against or even attacking the photographer – they are not compliant. The photographer, the male photographer, depending on which way up you decide to have the image, might even be turned on his head. That was the kind of thinking behind that work. It is about power relations – hence the title.

PB: Two works, both of 2000, that were also included in the show, operate very differently: Panchromatic and Untitled Interior (15.7.00 and 18.7.00). They appear to invite the viewer to enter a shallow space in seemingly conventional perspective, but then entry is denied or baffled by the edge or periphery.

JH: The space is both three-dimensional and two- dimensional because the lines of perspective are actually ruptured as well as continued by the overlaid image. In respect of Panchromatic, the overlay is a completely black-and-white rendition of the otherwise coloured central part of the picture. In Untitled Interior (15.7.00 and 18.7.00) the figures refer to two dates. It is a time-lapse image. The room was at first in a derelict condition and, over a period of two or three days, I restored the space to a kind of white cube perfection and then re-photographed it from exactly the same position. All this time the camera just stayed in place on its tripod without being moved so the second shot is identical to the first shot except for the fact that the room has now been redecorated and, as with Panchromatic, the restored central part of the image is overlaid onto the background – quite literally, one photograph is glued on top of the other – so there is definitely a rupture. You have a sense of being able to enter, as you say, but at the same time there is a two-dimensional panel across the image, which is now both accessible and blocked.

PB: The black-and-white ‘inner’ image in Panchromatic is framed by what appear to be CMYK colour bands.

JH: It is actually a mixture of CMYK and RGB. It’s a kind of hybrid which is impossible to achieve because the blue of RGB isn’t quite the same as the cyan of CMYK and so on. Rather than being a precise equivalent of the two systems, it’s an approximation.

PB: Together they form a kind of diptych since in Untitled Interior the image of the white cube is superimposed on the paint-spattered wall of what looks like a studio wall – photography superimposed over painting.

JH: In both cases, and in numerous other works, I hand-painted the interiors, so my connection to painting isn’t entirely without substance! In Untitled Interior the wall had been graffitied and then sanded down, which is exactly what gives it that rather colourful painterly effect.

PB: It suggests an abstract expressionist painting, and abstract expressionist painting is usually masculinised; its macho character has been critiqued by artists as various as Mike Kelly and Cheryl Donegan.

JH: Of course that’s a feature of Miss Tracy as well. I’ve written about that work and I say the background sheet is like a butcher’s cloth because it is so bloodied, but it is also like an expressionist painting that has been splashed and stained in a very energised way.

When we started talking about Miss Tracy you referred to it as Study For Miss Tracy – but actually, the original work was quite large. It’s about 2x2.5m – the size of a certain kind of large-scale painting – and it is also printed in ink (this is an early form of inkjet printing) on to a vinyl substrate and stapled over a wooden stretcher as you would a canvas. I mention that because it is not just the expressionist application of theatre blood that has a painterly reference, it is also the scale and the means of printing and the substrate itself which references painting. Speaking of the masculine affiliation of Abstract Expressionism, Miss Tracy has attracted a surprising array of interpretations, one of which identifies the subject as male, not female.

PB: I noted in the show you had a piece from 1998 called Fallen (Into The Light). It looks like a deposition or entombment or lamentation – or an amalgam of all three. I couldn’t identify it, though the lighting made one think of Michelangelo Caravaggio.

JH: There is a reference specifically to paintings of the deposition but not to any particular painting. It is a generalised reference to the genre.

PB: What draws you back, again and again, to painting and to art history?

JH: As a fine art student, even though I was making sculpture, I always had a great deal of interest in contemporary painting and I wasn’t working sculpturally in a figurative way – quite the reverse. As you said, I referred to my sculptures as being presentational, not representational – so they were wilfully far away from any kind of figurative depiction.

The paradox of using photography, for me, is that I was employing what’s actually a representational medium to record and then displace non- representational work. Photography, after all, is also largely a figurative medium, so when you begin to compare photographic work with other kinds of figurative two-dimensional work, you are likely to generate an interest in figurative painting from throughout history. With regard to Renaissance works – from frescoes to easel painting – I do have an interest that is partly born of a desire to make that comparison: what can, and what does, photography do? What are its assets, but what are its deficiencies? What can figurative painting do? And, similarly, what are its assets, what are its deficiencies? I had obviously decided there are some assets that I would like to try to import into photographic work. Hence those pieces we talked of which I think of as being transcriptions and which all have in their title the designation ‘after’, a classic way for photographers or, for that matter, printmakers, to indicate images that are copies of existing works by other artists.

PB: There is a great deal of work at present that is the result of commissions to work with archives. Some of the work is, quite frankly, less interesting than the contents of the archives themselves. You have recently made works based on the plaster collection in the Royal Academy Schools in which you have brought your own aesthetic to the project, treating the archive simply as a subject like any other for your photographic interrogation. And yet, in so doing, you have achieved exactly what such a project should ideally do, which is to animate something that, in the case of the RA collection, was literally about to be (albeit temporarily) relegated to the vaults of history – out of sight in the cellars during scheduled rebuilding work. This is one of the things photography can do other than simply to record. Was this the result of your own initiative, or were you approached by the Royal Academy?

JH: Oh, no, it was my initiative. I was probably just a nuisance, I think, but they were incredibly tolerant and helpful and I’m very appreciative of that. In the past I’ve done one or two works which were commissions but experience now tells me that my practice doesn’t lend itself easily to those sorts of constraints. I’m much happier working entirely on my own initiative – so I haven’t done anything like that for quite a long time. Now, even if I do go into some kind of institutional context, it is almost certainly going to be because I have developed my own need to be there.

PB: One of the works I particularly admired in the exhibition was Four Monochromes Not Registered (Cyan Over Yellow Over Magenta Over Black) of 2004. Again, this relates to some of your earliest works like Red Coat/Blue Room and Green Trousers/Red Room of 1969, both of which dealt with complementary colours. In Four Monochromes you use all the colours to negate colour and, in so doing, you create the ultimate modernist icon – the black square. When did you begin making these works using multiple exposures?

JH: You were talking earlier about works which I described as being aggressive towards the spectator in which the largest and central part of the picture, where you would expect to find the intended centre of your attention, was screened out one way or another and rendered as an opaque plane with all the ‘interesting’ events only to be found in the periphery. Having reached a point where I felt that I had done as much as I wanted to do with that idea, I suddenly decided to do almost the opposite and return the identifiably interesting element of the image to the centre and actually have the periphery now more confused – but not just to return that central element to where it belonged, let’s say, but to do it emphatically – not just once but again and again and again.

Actually, the very first work I made of this kind had that as its title: Again And Again And Again. I think that was in 2002 – so let’s say that’s the starting point of those works which, you could say, are about point of view. They asked the question: should I photograph this object from here, or over here, or possibly over here? Because, actually, even if the object is wholly symmetrical such that at any point of view facing towards it from around a 360° periphery it’s always going to look the same (at the same height and distance), it will register differently from different positions because, almost certainly, whatever surrounds it and is behind it will vary. So, those works were based on that idea.

PB: Another work related to that is Division of Labour, also of 2004, and it, too, lays out the tools of the trade all around an apparently blank canvas or unprinted piece of paper.

JH: It is exactly that – it’s a tabula rasa. The studio, which looks like a real mess in the finished image, is recorded using a quadruple exposure. Actually it was very ordered so that one entire side of the studio was filled only with the media and tools of painting, and another side only with the media and tools for making film or video, and so on, with photography and also with sculpture. The only thing that retains its coherence is that tabula rasa which is a metre-square sheet of – well, we don’t know what. It could be blank photographic paper, it could be blank paper or canvas, it could be a blank element for a sculptural construction, or it could be a projection screen for film and video. It is intended to reference all those things. It is waiting for its subject and is surrounded by the various means by which that subject could be introduced.

The thing about Four Monochromes Not Registered is that, rather than being an exposure of a fixed object at the centre of surrounding viewpoints, there are actually four monochrome prints – black, magenta, cyan and yellow – placed at the centre of the four walls of a print studio so the camera now is actually in the middle of a space pointing outwards towards the periphery – that’s the difference. But otherwise it’s still a quadruple exposure and, of course, those four colours are the CMYK colours that we spoke about previously and the room itself is white – so, altogether they should be capable of delivering every colour and, of course, they mixed to a sort of muddy nondescript sludge which I particularly enjoy.

I didn’t just make one shot; I made several shots, but I made them in different orders – so magenta might be over yellow over cyan over black but, equally, yellow might be over black over magenta over cyan – and, depending on the order in which you make those superimpositions, you will get a different colour.

This is partly a tribute to monochrome paintings by Bob Law, and I mean that quite seriously. I always had a great interest in the paintings he made which, seemingly, were black monochromes but actually were arrived at in the kind of way I’ve described but through painting, by painting layers of different colours on top of each other to get, in the end, what might have been a plum black or a green black or a purple black. You didn’t really see that so easily until you saw a collection of them in a single space and then they hummed, vibrated, with these colours.

PB: You started out by saying that your interest lay not in the photography of objects but in photography as an object in itself which, as you say, is a modernist stance. But in our conversation we have roamed through film, photography, sculpture, painting, art history – all seen and discussed through the medium of photography. When you asked yourself, ‘what can photography do?’, it seems it can do a hell of a lot. What other things would you like to do with it? In other words, what are you working on now?

JH: I’m working on some pieces that actually stem from a reflection on photography as a medium which, as a rule, is repetitiously consistent in its structure. I mean, starting with analogue photography, with the simple fact that a photograph has a grain structure which is present all across and throughout the whole image. The same is true with digital photography in terms of pixelation. But more than that, I think most photographs which depict something in a particular way – let’s say in soft focus, for example, or maybe a picture is taken with the camera in motion, or maybe a picture is taken with everything dramatically over-exposed or under-exposed – in each case those features will usually apply throughout the image.

It interested me to try and make works which have built into them a certain kind of variety. Some of the elements I have just mentioned might be co-present within a single picture space. I made one or two works where, either within the camera itself or in, if you like, post-production, two or three shots of the same subject have been combined. I tried to make works so that a variety of features existed within a single work and one of the features I became interested in was that of enlargement, where you might discover, even after the fact of taking a picture, some content which wasn’t noticeable to you when you made the picture in the first place and, perhaps, wasn’t even noticeable to you when you first started looking at a print, but something you discover subsequently.

PB: I see on your bookshelf right in front of me the catalogue for Blow-Up. The movie came into my mind as you were speaking.

JH: It is especially pertinent to point to that because it’s actually a catalogue of an exhibition of works relating to the film Blow-Up that was initiated by the Albertina Museum in Vienna. I had two works in that exhibition but, in fact, the works of mine that were first considered for the show were pieces that did, indeed, enlarge from a single photograph a particular detail, possibly to the point of oblivion and, as you know, that’s a central feature of Antonioni’s film.

The works of mine I’m referring to are actually from 1971. We started off with you talking about the repetition or recapture of certain ideas throughout a lifetime’s work. I certainly do find that sort of recurrence, not really deliberately, not really consciously at the outset, but certainly on reflection one notices these things and that’s an example.

PB: Could you talk about some specific works dealing with enlargement in this way?

JH: Well, for example, there is a work called Cover Stories which takes details of an image of bookshelves, in this case bookshelves filled only with crime fiction, and enlarges monochrome areas from the book jackets – from the spines of the books – where there is no text; there is simply a single colour, and because of the shape of the books, those enlargements tend to be vertical rectangles, narrow to the point of being describable as stripes. I have taken not just one enlargement, but a number – let’s say 20, for example – and put them all together into a single block. So you have now got something which is deliberately referencing hard-edge striped painting and this is overlaid on the image of the books. The books themselves are really only accessible around the edge of the whole image, but with enough information to allow you to cross-reference and discover from where some of these enlarged details have originated. But between the background books and the central block of coloured bands there is a real difference in the structure of the image. I was talking earlier about the granular and pixelated homogeneity of the photograph. Well, the grain and, indeed, digital ‘noise’ are discernible now in these works, simultaneously present in dramatically different scales, resulting in very different readings.

PB: We talked earlier about Modernism and photography and there are purists who wouldn’t touch digital – but this is not where you stand at all.

JH: I think if we talk about Modernism, there ought to be purists who will only work with digital photography. When I was teaching at the Slade, I used to talk about the ‘toolbox’. There are many methods and devices which allow for different ways of working – it could be charcoal and sugar paper or it could be acrylic paint and canvas or it could be bronze casting or it could be digital video. My thinking always was that whatever came along that you could add to the toolbox, you add it – but you don’t throw anything out. You still leave yourself that entire range of options. With photography, when I first started using the medium, the only option was film. As digital photography has entered into the medium and invaded it and, for many people, completely displaced analogue photography, for me it’s not something to be resisted. It is something to be considered and to make use of, and there are certain areas where it is actually more efficient, more practical to do a certain job digitally. So, even though I still shoot everything on film in the first place – or almost everything – I do frequently use digital means to progress things in particular ways. My feeling is that hybridised works usually throw up something interesting – or perhaps this is just another example of wanting to have one’s cake and eat it.

Patricia Bickers is editor of Art Monthly.

First published in Art Monthly 386: May 2015.