Review

Leah Capaldi: Big Slit

Cherry Smyth finds herself alive in the livefeed

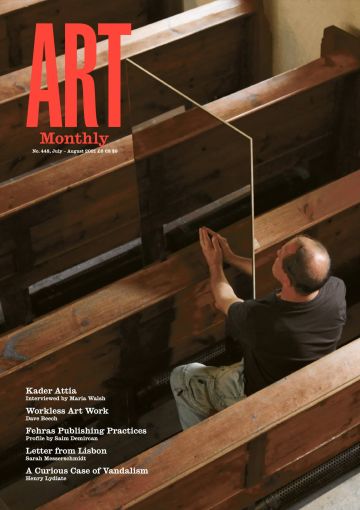

Leah Capaldi, Big Slit, 2021, clip from CCTV livestream

You walk into a gallery. No, you mask up and walk into a gallery. No, before you mask up, you’re asked if you mind being on camera, being part of a livefeed to the website. Do I mind? Can I object? Haven’t I been filmed many times on my journey here? But this is the only time permission has been sought and I’m suddenly hyper-aware of my body, its movements and its meaning in the space: the body of a critic. Much of this swift self-judgement usually happens in the galleries of the high altar, those spaces observed by dispassionate interns, but this provocative set-up asks me to recognise how much is absorbed by having a certain body and getting used to it: its gender, style, age, race, shape, profession.

So, first, locate the cameras. Tick – two. The white cube is constructed within the walls of the building, with an inviting vertical gap in one wall, emitting an aqua light. A knee-high plank bisects the gallery and disappears into this opening. At a distance this recalls both the minimalism of Dan Flavin and the architectural peepways of Gordon Matta-Clark. Up close, through the slit, there is a naked human foot and calf resting on the plank. There’s something happening or nothing happening, depending on liveness. It could be an escapee from Ron Mueck’s or Robert Gober’s menageries or a lowly paid model. It turns out to be a breathing man, dressed in non-binary half leggings (black) and T-shirt (white). Should I mention that he is white? I take it that he stands in for all of us: that his maleness and whiteness are not incidental. A female or a gender-neutral body, a black or a brown body would mean there has been, or there is about to be, an incident. Is this a sign that nothing intersectional is going to happen, unless I make it happen? By lying on the floor, motionless and silent, the man is rendered vulnerable and feminised, and does that make me, walking noisily around the space and enjoying a certain voyeuristic pleasure, empowered and masculinised? Or is it simply a sign that Leah Capaldi has mastered something as Marianne Morris writes in ‘Wisteria Under Capitalism’: ‘I mastered myself so as not to be slammed shut / or made small, it turns out / it isn’t about essential categories / of masculine or feminine at all’

I want to know if the man is asleep – no, he blinked – if he’s meditating – hard to tell – and then if he’s regretting lying immobilised after the year (plus) we’ve had of agonising isolation. Is his foot cold, his leg numb? Am I keeping him company? Is this his dissertation? I want to mirror his pose in a burst of solidarity, lie on the floor and sling my leg over the plank on my side. Too self-conscious, too performative, too show-stealing. The etiquette of spectator behaviour floods in. I won’t speak or knock on the wall. I try to be quieter. Empathy tears at me. I’m in a Martin Creed piece that’s morphed into The Artist is Present via a proxy. I am a prop in Capaldi’s theatre. Oh, but I want prophood. I cherish agency as he seems to have none. He swaps his legs over. I am relieved. Is that a timed gesture? Is he in detention? When does he get a break? Two letters flop through the letterbox on his side of the wall, interrupting the skin Capaldi has built and revealing another smaller slit into the space. I have a slit, he does not. (Well, there again, they might have.) Lack enters the room via the slit/no slit.

I remember I can watch him on my phone. I can watch myself watching him. The layers proliferate as I switch to the livestream. One camera films him from the ceiling and I can see his whole body. I want him to perform more: sing, groan, speak: be Vito Acconci for this age. Is this dissatisfaction or expectation of the contract between performer and spectator? I like the questions. I observe the answers. Funny that my desire increases and empathy lessens when we are both small images on the screen. I expect a Zoom chat, perhaps. I can also see the slit from his point of view which means that I have been filmed peering in. This is the most violating of the camera angles and the perspective will have revealed my ocular greed, only half-concealed by my mask.

There is a strange osmosis going on: I move in the space and want his stillness; I want to perform and am glad he’s the ‘performer’; I want to be watched and am entrapped by unknown watchers. I both envy his isolation and want to alleviate it. Here’s the claustrophobia of lockdown enriched by its blissful lack of choice. If sculpture is ‘a state of mind that the object inhabits’, as Capaldi suggests, I am sculpture, I am material. Later, I look at the livestream to see how he’s doing. He’s my Tamagotchi and my look feeds him.

Leah Capaldi’s ‘Big Slit’ was at Matt’s Gallery, London, 21–30 May 2021.

Cherry Smyth is a poet and writer.

First published in Art Monthly 448: Jul-Aug 2021.