Report

Learning to Unlearn

Greg Thomas reports on the Ignorant Art School series of exhibitions

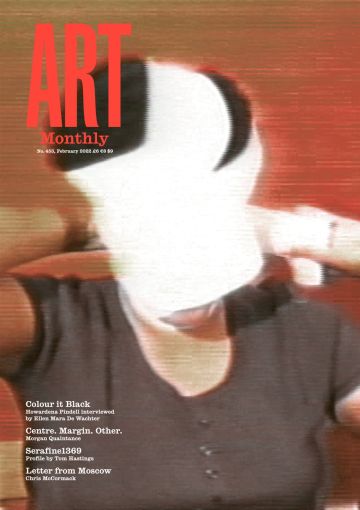

Ruth Ewan, How Many Flowers Make the Spring?, 2021

Jacques Rancière’s The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Creative Emancipation from 1987 recounts the story of Joseph Jacotot (1770–1840), a teacher in post-revolutionary France who was forced into exile by the Bourbon restoration of 1814 and became a professor of French in the Netherlands. Despite knowing no Flemish, and therefore being unable to teach his students, Jacotot discovered to his amazement that they were able to teach themselves, using only a bilingual edition of François Fénelon’s Télémaque and the instruction – conveyed by an interpreter – to piece together the meaning of the French text through comparison with its Flemish counterpart.

This revelation was the spur to Jacotot’s philosophy of ‘intellectual emancipation’, based not so much on any teaching method as on rejecting the idea of explication per se as necessary to learning. All that was required for a student to learn was for their teacher to place them in a stimulating relationship with an object of study, which they would find ways around and through using their native wits. The inadvertent success of Jacotot’s method suited both his own Rousseauian idealism and Rancière’s Marxist humanism. In post-1968 France, it also seemed to provide a model for radical social progress, foregoing systems of academic authority that implicitly upheld the values of bourgeois society even while facilitating its critique.

It is hard to imagine a recent period in British social history when the revolutionary potential of arts education – indeed higher education in general – has seemed so distant. The co-option of universities by market logic is evident in the mass casualisation of academic labour and instrumentalisation of the ‘student experience’ as a pragmatic accrual of cultural capital. And yet the chalkboard sign that currently greets visitors to an exhibition series at the University of Dundee’s Cooper Gallery quotes bell hooks’s 1994 book Teaching to Transgress: ‘the classroom, with all its limitations, remains a location of possibility. In that possibility we have the opportunity to labour for freedom, to demand of ourselves and our comrades, an openness of mind and heart that allows us to face reality even as we collectively imagine ways to move beyond boundaries, to transgress.’

It’s no criticism to say that one of the strongest emotions I felt on exploring the many case studies of alternative art institutions and educational projects which constitute the second show in the Ignorant Art School series, ‘To Be Potential’, was a kind of dull sadness. The promise of arts education as collective intellectual emancipation, the fostering of new bases for cultural and societal organisation, has seemingly been so sporadically realised at an institutional level that examples of it are literally exhibition pieces: traces of a kind of counter-factual history. Nonetheless, the energy and ambition of the Cooper’s five-part project – modelled on Rancière’s five lessons – is impressive and, with all due provisos about wider realities, inspiring.

Talking to principal curator Sophia Hao, I’m struck by her unapologetically ideas-led approach to curation: this is not a series staked on blockbuster visuals or sensory delights. The Ignorant Art School is her brainchild, and it is informed, she says, by three ideas: ‘It’s about what happens in art schools, of course, but it’s also an investigation into knowledge production in society as a whole. The show looks into our assumptions of what knowledge is, how it’s shared as a social act, and how knowledge bears the pressures of the violence of power. And thirdly, the project aims to emphasise the idea of knowledge creation as a collective experience, a site to build communities of resistance.’

It is hard to know where to start with the stories told by ‘To Be Potential’, such is the glut of multimedia resources that happily assail the visitor. The narrative begins chronologically with the Bauhaus, whose model of interdisciplinary, praxis-led learning informed the development of the Basic Course in Britain during the 1950 and 1960s, but the audience’s first encounter is with a set of posters, broadsides and essays recalling the history of London’s Anti-university and the Free University of New York, alternative HE institutions on a 1960s anarchist model. Both were lodestars for Jakob Jakobson, a Danish artist and activist whose Copenhagen Free University picked up their thread of emancipatory potential in the early 2000s.

Upstairs, we are transported across historical and contemporary sites of egalitarian creation, from the Hornsey Sit-In – the subject of some striking lino-cut prints, which are among the few unambiguous ‘artworks’ on display – to the Womanifesto series of gatherings in Thailand. The latter began in the 1990s, exploring connections between local and international artistic cultures and serving as pretexts for communal creative activity. As these examples might suggest, the show is both geographically and historically far-reaching. Indeed, the Global South is revealed to be a livelier site of communalist arts pedagogy in the present day than the North. Indonesia’s Gudskul, for example, is a collective formed in the early 2000s that offers a year-long informal study programme, Gudskul Collective Studies, on topics such as ‘Collective Practice Intelligence’ and ‘Collective Sustainability Strategy’. In a comparable vein, Hong Kong’s Rooftop Institute was founded in 2014 by artists hoping to encourage discussion and activism on cultural and social issues using artistic creativity as a prompt.

Earlier in 2021, Ruth Ewan’s show ‘We Could Have Been Anything That We Wanted to Be and It’s Not Too Late to Change’, the first instalment in the Ignorant Art School programme, followed a more site-specific line of enquiry, taking us beyond the walls of the academy while homing in on local radical traditions. Known for her works on radical social history, including her ten-point decimal clocks memorialising the ten-hour day initiated in revolutionary France, Ewan grew up near Dundee and is therefore familiar with the city’s socialist heritage. This includes its traditions of female activism, from Dundonian women’s suffrage – both ‘particularly militant’ and ‘pretty bloody funny’, she tells me in interview – to the Timex strikes. ‘Dundee also has this connection to the French revolution’, she says (in 1793 a Tree of Liberty was planted in the city in honour of the French government, and the fervour it stirred up led to riots), ‘and I feel that reverberates through the city somehow.’

The intersection of the comic and the committed, together with an archaeology of dissent, marked Ewan’s contribution to the Sit-In series. In the stairwell of the gallery during her tenure, a backlit text-bubble in the unmistakeable style of a Bash Street Kids comic strip – whose publisher, DC Thomson, is a loved local institution – bore the slogan ‘no more boss class history’ (Heckle, 2021). Lockdown also prompted the artist and gallery team to plot a series of online events during spring 2021 exploring the legacies of activism in the city. Featuring various contributors, An A-Z of Dundonian Dissent took audiences from ‘Anonymous’ – ‘the activists and agitators whose names we do not know’ – through abolitionist Frederick Douglass’s visit to the city, jute mills and on to Generation Z.

A stand-out work in scale and spectacle was Ewan’s How Many Flowers Make the Spring?, 2021, an indoor wildflower meadow consisting of grasses, weeds, seed-heads and potted blooms, many foraged from close to the gallery. Concealed within were speakers playing interviews with activists of various generations, each recounting a formative political event, from anti-Vietnam marches to the Battle of Kenmure Street in 2021, when protesters in Glasgow prevented a Home Office van from detaining two Sikh community members. ‘I wanted this meadow-like landscape to represent a mass of people. And I wanted things that were native but also invasive plants,’ Ewan recalls. In its evocation of collective land ownership and subtle metaphors of ineluctable growth and decay, the piece offered a monument to the inexhaustible but often seemingly exhausted wellspring of political idealism.

Today’s art schools might not feel like places for intellectual emancipation, but what this series of exhibitions could help us to conceptualise is the survival of a tradition in its recesses, in snatched moments of dialogue, excitement, remembrance. The classroom remains a site of possibility.

‘The Ignorant Art School: Sit-in #2: To Be Potential’ continues at Cooper Gallery, Dundee to 19 February 2022 before touring to Hatton Gallery, Newcastle, 19 March to 21 May 2022.

Greg Thomas is a critic and editor based in Glasgow.

First published in Art Monthly 453: February 2022.