Report

Letter from Korea: One Step at a Time

Chris McCormack reports on the Gwangju and Busan biennales at a tentatively hopeful time in Korean politics

research image for Tom Nicholson’s Stranger at Fountain 2018

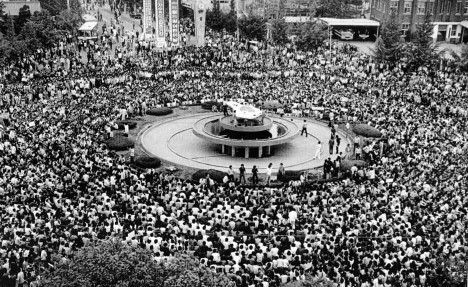

photo depicts the Gwangju Uprising of 18-27 May 1980

I arrived in downtown Gwangju for the 12th edition of the Biennale – this year titled ‘Imagined Borders’ – under a display of military jets practising manoeuvres; they provided a striking reminder of the competing hard and soft powers that distort and define the global image of the divided Korean peninsula. Against this political backdrop it is perhaps a curious inversion that Seoul-based chief curator, Sunjung Kim, invites us to ‘imagine’ borders when the hardest of hard borders – the mile-wide Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) no-man’s-land which separates the southern Republic of Korea from the northern Democratic People’s Republic of Korea – is so physically present. Also acute are the conditions for South Korea’s influx of Yemeni refugees arriving at Jeju Island, which has sparked debate on the county’s role on accepting asylum seekers. More optimistically, discussions in Korea have recently shifted to one of tentative reconciliation across the North/South divide, potentially signalling a close to the brutal ‘Forgotten’ war and ensuing 65-year stand-off between the Koreas, perhaps most significantly witnessed in April this year when North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un and democratically elected South Korean President Moon Jae-in crossed the border together and reportedly shared jokes. Such diplomatic efforts were alluded to during the Biennale press conference when the curators were asked whether the thaw between the countries might see greater cultural exchange in the coming years, a question that was met with wry smiles. One step at a time it seems, although a small selection of rarely shown North Korean Chosonhwa paintings – life-size Soviet Realist-style watercolours on rice paper – brought in via Beijing by BG Muhn, signalled some change, even if their provenance is fetishised by the West; these works have so far received the most press coverage.

The Gwangju Biennale is a complex, handecagonal curatorial arrangement organised over two large main buildings, the Asia Culture Center and the purpose-built Biennale hall, with several off-site projects. Not counting the three international pavilion projects, the Biennale still clocks in at 165 artists from 43 countries over seven exhibitions. Eschewing the sole, grand exhibition helmed by an already internationally recognisable curator (previous iterations were headed, for example, by Maria Lind, Jessica Morgan and Massimiliano Gioni), this year’s Biennale opted instead for 11 curators, invited by Kim, to present a series of exhibitions that furrow independent lines of enquiry, loosely unfolding the Biennale rubric of nation-building and migration. The decision to produce a biennale on such an ambitious scale, after last year’s gamut of Documenta, the Venice Biennale and the Münster Sculpture Project, led to frequent conversations during the opening week about what a biennale can conceivably achieve, particularly if the copious artworks drain rather than enrich engagement, inducing biennale fatigue, but also whether it is still necessary to represent such an exhaustive global survey when there is increasing access to work online. Perhaps more pointedly, many wondered how a biennale might better reward artists with fees, research time, access to materials, technical support and space to make works, rather than seemingly squeezing as many artists as possible into the ambitions of curatorial research projects.

Overall, a relatively straightforward approach to exhibition making was seen throughout (with the exception of an archival project by David Teh which comprises a reading lounge and series of platforms for discussion). ‘Imagined Nations/Modern Utopias’ opens the Biennale with an aesthetically coherent if subdued selection of works that circle regional modernist legacies from the global south, alongside traces and influences of colonial architectural design: a thesis so specifically conceived that one could easily imagine it transplanted to any museum as a standalone show, raising the question of what defines a biennale exhibition if not the unwieldy nature of it. Curated by Clara Kim, Tate’s senior curator of international art, the exhibition wove together unwritten histories, such as Ala Younis’s work on the influx of modernist architects in Iraq from the 1950s onwards. Younis speculates on the overlooked work of female architects at that time, such as Ellen Jawdat and Amal Kandalaft, and the influence they had on designs, centring on Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s designs for a gymnasium, which were perhaps surprisingly completed during Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship in the late 1970s (Hussein’s taste for ostentation and gold taps must have developed later).

Canadian artist Terence Gower presents two opposing newspaper reports on the history of Curtis and Davis’s modernist-designed US Embassy in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) from the late 1960s, one from Washington, the other from Saigon. By recreating a section of the signature inverted diamond windows in concrete, Gower cites the modernist language of openness while gently underlining US foreign policy’s need to protect and withstand enemy attack – the metaphor of present-day political division in Korea is writ large.

Elsewhere, the queer delirium of Zach Blas’s video Contra-Internet: Jubilee 2033, 2018, stood out, alongside Shu Lea Cheang’s digital animation work UKI Virus Rising, 2018, which makes an assault on technology’s attempts to ensnare post-gendered bodies. Stanya Kahn’s diaristic video of shared intergenerational histories and the labour of protesting in the US homed in on physical care and its fragility against a disorientating array of found-footage clips featuring anti-Trump demos, police shoot- outs and ecological meltdown. Kahn’s view is refreshingly holistic.

Protest has been central to the Biennale since its inception in 1995. The siting of the exhibition in this predominantly working-class city directly stems from the history of protests for national democratic rights, which boiled over in 1980 and led to a massacre of over 600 people, many of whom were students, by the local junta. This violent history has been returned to throughout the history of the Biennale, and is again referenced in several works. Whether the return by successive Biennales to this subject is necessary ballast against quickening political amnesia or, as some have argued, a curatorial crutch that needs removing to enable a more forward-thinking Biennale, is a divisive question. Notably, Tom Nicholson’s free publication reprints speeches delivered by protesters during the several days of reprieve from the junta – a small window of optimism – before it returned in force. Nicholson invites readers to recirculate the texts at the fountain where protesters first gathered, quietly invoking the voices of those who were killed. The archival section also gave space to Lee Ungno’s ‘Foules’ series that evokes aerial views of crowds in flight or a pulsing sway of cohesive attachments, now seeming like echoes of a globalised embrace which, as curator Teh observed when reflecting on the cultural shifts since 1995 when the Biennale started, ‘is not so optimistic anymore’.

A four-hour drive west took me on a brief trip to see another biennale, the thankfully smaller-scale Busan Biennale titled ‘Divided We Stand’, curated by a committee led by artistic director, Cristina Ricupero, curator Jörg Heisser and guest curator Gahee Park. Busan is comparatively richer and typically more conservative in its outlook than Gwangju (tellingly, the main Biennale venue is rented from the housing museum rather than organised in collaboration), while its coastal location and renowned steam baths secure tourism, principally from Japan.

Heiser presents a nimbly idiosyncratic approach to curating with often pinball-like associations – for instance, ‘Divided We Stand’ is also the title of an episode of M*A*S*H – bringing together an unnerving array of paranoid conspiracies that often insert Cold War narratives into that of the Korean stand-off. The exhibition unexpectedly opens with the prologue to Lars Von Trier’s 1991 film Europa, which hypnotically asks us to go ‘deeper into Europa’ while its looping grainy images of train tracks imply Holocaust trains or Céline-like ennui with the doomed project of Europe. Other works imply hallucinatory drug-induced visions, like the drawings of Suzanne Treister or Oscar Chan Uki Long’s wall hangings, while historical fragments fall into orbits – or better yet, ‘zones’ – that occasionally cohere or lose their way, such as Chin Cheng-Te’s American Pie, 2016, a personal archive of Korean and Taiwanese cultural paraphernalia burnished by US-military influence.

One stand-out work from across both biennales was Minouk Lim’s It’s a Name I Gave Myself, 2018, which lifts footage from a KBS national television show in 1983 which sought to reunite relatives scattered between North and South Korea, and those separated under Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1945. The programme was meant to run for two hours but was swamped by thousands of people seeking to find loved ones both in the studio and on the streets outside the studio, which the artist recalls watching at home in awe. As they were often separated as children and given a new name, they identified each other through the smallest of shared memories – such as a scar made by a falling tree or a nickname. The moving testimonies are presented in a strange diorama made by Lim that recreates the television studio, populated with figures and objects torn from the sometimes bizarre and personal recollections that starkly stand in as mute traces for the suppressed stories.

Poet Ko Un observed that the 1950s was a time when more than half of Korea had been reduced to a scorched wasteland, the cities were in ruins, and the people who survived were ‘lost like scraps of broken brick amongst the ruins’ for whom ‘no future seemed possible’. Lim’s work signalled that the wastelands of Korean history are still to be traversed.

Chris McCormack is associate editor of Art Monthly.

First published in Art Monthly 420: October 2018.