Report

Outer Spaces

Greg Thomas reports on the rise of short-let artist-run spaces in Edinburgh city centre

Dissenter for Space Studies, Edinburgh

In the former headquarters of Royal London Insurance in Edinburgh’s salubrious Stockbridge district, artists Nick Evans and James Rigler are talking about the Sculpture House Collective in front of an intimate and attentive crowd. The collective, formed with Laura Aldridge, runs a converted town house in Paisley as a community space and collective studio, paying rent in the form of artistic labour. This imaginative approach to artists’ spaces is being discussed in the ambit of another: 57 Henderson Row has been renamed Dissenter for Space Studies for the duration of a project overseen by curator Claire Feeley, draped with banners designed by Luke Cassidy Greer and screen-printed by Sarah Gillespie that match the corporate colour scheme.

Dissenter (the centre/dissenter – geddit?) occupies one of a number of central urban spaces, mostly abandoned office blocks and retail units, that have recently become available across Scotland and the UK as ‘mean- while’ short-term lets for artists, offered on peppercorn rent. Landlords get rates relief or other benefits from properties let in this way as long as artists are visibly present; they can also cancel the lease at short notice if a new corporate tenant comes knocking. This is the kind of deal being brokered by a new charity, Outer Spaces, founded by Shân Edwards, which offers spaces for free, and supports Feeley through a bursary as one of several curators-in-residence to help artists customise and work around the constraints of their dwellings.

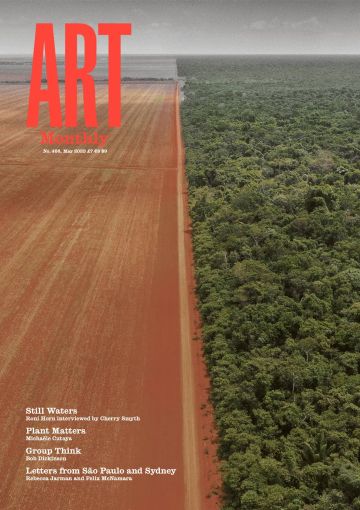

‘Fifty percent of the building stock in Edinburgh city centre is either insurance or bank buildings,’ Feeley tells me, ‘but the working patterns that sustained those spaces have fundamentally changed since the pandemic and they’re not going back. So increasingly, rather than artists being on the outskirts of cities in empty warehouses, they’re right in the middle, in these empty cathedrals of finance.’ The hybrid-working patterns of the post-Covid world have commingled with the longer- term impacts of austerity and gentrification – which have eroded the older model of post-industrial studio space Feeley alludes to – and the move to online retail that has gutted high streets (see Matthew Noel-Tod’s ‘High Streets for All?’ in AM446). This confluence of events has brought an increase in both supply and demand for the kind of package Outer Spaces offers.

In spite of the role, Feeley is blunt about the potential drawbacks of the model. ‘These meantime lets can sometimes be a bit shit. There’s no guarantee that they’ll work as studio space and its unlikely there’ll be a building manager for maintenance. And given that landlords benefit financially from artists via rates relief the eviction terms can feel pretty punitive.’ Furthermore, ‘because the artistic labour has to be visible, it can inadvertently create this situation where certain practices seem to have more legitimacy than others. A writer’s labour won’t leave the same evidence as a painter’s, say. The Dissenter began in response to this requirement for us to perform our artistic labour and what that meant for us as a community.’ There are also heavy restrictions on renovations or alterations: ‘People get told “do anything you want” but then, “oh by the way you can’t touch the walls or mark the floor”.’

The Dissenter for Space Studies, Feeley suggests, is partly about acknowledging these drawbacks as a way of framing the positive potential of such spaces. ‘In a way it’s fine when these provisos are on the table ... where it becomes potentially problematic is where it’s wrapped up as this amazing opportunity and the conditions aren’t made explicit.’ In tandem with this central aim, Dissenter spotlights like-minded initiatives, such as Sculpture House, and creates space for voices and groups that are ‘decentred’ in other ways within contemporary artistic culture: from minoritised creatives to artist-parents. Feeley’s first commission was for an experimental baby-change unit, created by studio-holders Rebecca Subido and Laura Richmond.

To help set the right mood, Feeley also invited architects Robin Ellis and Thomas Woodcock (WoodcockEllis) to create an architectural environment for Dissenter, specifically for its open-plan former canteen (not a 1960s brutalist hanger but a noughties neoliberal gustatorial boudoir, with curved serving counter and cushioned seating). Their intervention had to work around the constraints of temporary occupancy as well as reacting to a wider dynamic, what their project notes call ‘the fall of corporate environments and the precarious conditions of undervalued artistic labour’. At a pragmatic level, Ellis tells me that there were physical constraints they had to negotiate: ‘If the landlord wants to take on a new corporate client you have to clear out without a trace.’ The solution is elementary but brilliant: a series of curvilinear, gliding rails attached to the drop-ceiling holding wave curtains – the look is strongly influenced by Lilly Reich’s 1927 Velvet and Silk Cafe – hanging down around a central, carpeted space: a ‘world within a world’, the project notes call it. One small chunk of an uncanny post-corporate interior is terraformed for creative and social use, manifesting the safety and warmth of enclosure. Clusters of pot-plants express a semi-whimsical ‘rewilding’ of the office.

The space is also physically flexible. The rails can be rearranged in different shapes and the entire construction could also be removed wholesale and clipped into another empty office block; the standardised grid of drop-ceiling panels provided a handy degree of continuity in this regard. The design also incorporates aspects of the building’s existing aesthetic, creating a sort of post-corporate bricolage effect: ‘Various murals and collages and things had been left up,’ Woodcock says. ‘It was more interesting to leave some of this corporate debris, as a reminder that this is an in-between, ephemeral space.’ The choice of fabrics, meanwhile, and the colour palette with its high-vis pinks and silvers, hint at the ambience of emergency shelters and temporary dwellings, bringing a more disquieting quality: ‘ripstop, mesh and coated polyester speak to a new inhabitation of a decaying bureaucratic realm’.

The first event held in Woodcock and Ellis’s curtained cocoon, A Very Heavenly Social, was the brainchild of the collaborative duo Two of Cups, consisting of artists and programmers Saoirse Amira Anis and Laura McSorley. Those familiar with Anis’s sculpture and film work will recognise the spirit of warmth and geniality that defined this event. Running with Feeley’s invitation to create a strongly ‘social’ atmosphere, the pair curated a soiree of performances and talks by friends and associates responding to the theme of mutual care among marginalised creative groups. The invitation to participants asked for ‘odes (a song, a ballad, a story, a poem, a limerick, a toast, a dedication, a rant) that reflect your experiences of being a creative practitioner in Scotland. We are particularly interested in hearing about experiences of sneakily subverting the power dynamics that tend to prevent us from keeping our morale high and our pockets full.’

Anis and McSorley bring to the Dissenter discussion several years’ experience as voluntary board members for Dundee artist-run space Generator, so are able to articulate both the promises and the pitfalls of the ‘meanwhile’ paradigm. ‘I think it’s great what Outer Spaces are doing,’ McSorley tells me. ‘They’re providing spaces that people would never have had otherwise. There are lots of people programming who would never have got into that but suddenly they’ve got a whole shopping centre to work with.’ Then again, would they want an Outer Spaces let themselves? ‘I think it’s far too precarious,’ she says, ‘and there are those rules like “don’t touch the walls, don’t touch the floor”. You can’t craft a space like you could if you had it for ten years. It was great to work in Henderson Row as a one-off event but taking something like that on long-term is a very different thing.’

Having gathered these perspectives I speak to former CEO of Edinburgh Printmakers Shân Edwards, who has also worked in partnership with Hepworth Wakefield as head of The Art House. She was repurposing sites for artists for two-and-a-half decades before setting up Outer Spaces in 2021. ‘I first did it in the mid 1990s using three railway arches in Battersea that had been converted into office space. There were no takers because the country was in recession,’ she recalls, ‘so they became artists’ studios.’ Has the typical format of viable studio space shifted over that period? ‘In West Yorkshire there was a lot of empty warehouses: that classic, former-industrial space where artists can be artists without any consideration for the fabric or feel of the building. But when I came back to Scotland in 2018, what was available was empty office spaces ... There had been austerity, then Brexit, and then Covid. These things have hollowed out whole areas.’

Offering space free of charge, without stipulations on who can apply, trying to group artists together by practice and bringing in curators like Feeley to foster a sense of shared purpose – these are all part of Outer Spaces’s efforts to create a productive environment. Still, Edwards is fairly direct about what they are doing and why: ‘I don’t think temporary space is the answer for artists, ultimately. But this is an opportunity to seize now, because nobody knows what’s going to happen long-term.’ Offering one projection for the future, Anis tells me she hopes landlords will start offering spaces like Henderson Row at reduced rates on more secure tenancies, allowing personalisation of studios while drawing relatively low rent over long stretches of time rather than waiting for high-paying corporate tenants who might never return. ‘What I optimistically imagine is that these events around Dissenter highlight that these spaces that just lie empty can be put to better use.’

Greg Thomas is a critic and editor based in Glasgow.

First published in Art Monthly 466: May 2023.