Books

School: A Recent History of Self-Organised Art Education

Lauren Houlton reviews Sam Thorne’s survey of independent art schools

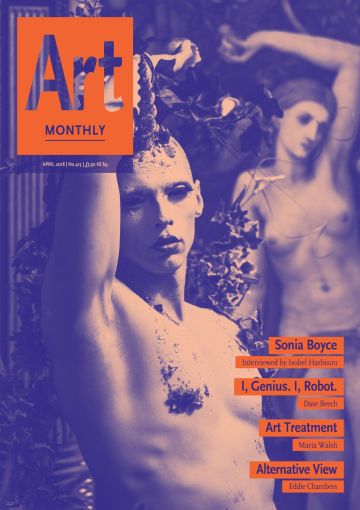

photo from Open School East used on the cover of School

In his introduction to the Central Saint Martins 2016 MFA fine art degree show catalogue, Paul O’Kane discloses the title of one of his first lectures: ‘About About’. I was reminded of this puzzling use of repetition, a form of word-trickery intended to destabilise this preposition by placing it in proximity to itself, by School: A Recent History of Self-Organised Art Education in which art education is presented as a space for revision and continuing questioning. Compiled by Sam Thorne, it comprises edited transcriptions of interviews that he has conducted with founders of 20 worldwide self-initiated art schools (in the book these have dfferent names – for ease they are referred to as schools throughout this review), whose scale, malleability and localised traits he views as much-needed responses to the current phenomena of debt-burdened students and the profit-orientated mechanisms of higher education, which he maps in his introduction. From curatorial experiments that take educational models as their structuring premise, programmes that intersect art and political activism through the circulation of suppressed histories and alternative bodies of knowledge, to education as an armature for the social assembly of diverse individuals, these schools, in keeping with the task of keeping art’s identity indeterminate, are multifaceted, offering a map of the myriad forms that an arts education has taken since 2000.

Though approached through divergent avenues and embedded in distinct political and cultural contexts, the ethos of these schools appears unified by a set of democratic principles which manifest through the creation of spaces that facilitate, through group discussion, the exchange and accessibility of a varying range of perspectives. The interview format of the book, therefore, not only allows the founders of these schools to self-define their motivations and activities, but also mirrors the discursive, collaborative framework that the majority of these projects privilege. Either through intention or limited resources, the activities of these education programmes have rarely been documented, so School doubles as an important archive, cementing the ephemeral nature of these gatherings.

The conversation format also grants the logging of immaterial forms of emotional labour, which are intertwined with discussions about funding. A handful of programmes are self-sustained, either through modest, low-fi means, such as organisers hosting sessions in their homes with speakers and contributing their time voluntarily, or through astute entrepreneurship, as demonstrated by New York-based collective Bruce High Quality Foundation University which, like non-profit gallery spaces, hosted an annual benefit dinner to raise money through patronage. These accounts of precarious, financial survival coincide with expressions of exhaustion caused by the essential but time-consuming nature of administrative work needed to co-ordinate the programmes’ delivery and maintenance. This is effectively captured by Ryan Gander in his attempts to open an art school, which repeatedly hit financial and bureaucratic roadblocks, and by Pablo Helguera when he acknowledges the disparity between the commitment necessary in long-term social practice and its financial viability and critical recognition.

Thorne’s questions, while punctured by brief excursions into criticality (such as when he asks Olafur Eliasson whether by locating his education institution next to his studio space he was simply replicating the same hierarchical systems of exchange that he was hoping to subvert) are mostly neutral and practical. As his interviewees are advocates of their respective schools, this inevitably results in conversations that preference the celebratory over critical inquiry. For instance, several examples of claims lingering unchallenged appear in the discussion about Open School East between Thorne, its three other co-founders and associate artist Jonathan Hoskins. These include the assertion that there is no demand for an organisation like OSE in Scotland, where higher education remains free, when many of the pilot year’s artists had already achieved BA and some MA qualifications; and while the sporadic and disorientating nature of the first term’s curriculum and the pressures of public productivity, which Andrea Francke is mentioned as raising in her contribution to a pamphlet collectively published at the end of the pilot year, are touched upon in the conversation, they are mitigated by an extensive list of the programme’s achievements. I wanted to hear from Francke about her concerns regarding the public learning model. A contribution from her would have given a far more diverse and balanced conversation, but the positive bias is perhaps unsurprisingly given Thorne’s connection to the organisation as co-founder.

One claim in particular, that OSE’s proposal came out of asking how an art school could be ‘rooted in its neighbourhood in a meaningful way’ struck me as worthy of further consideration. From the perspective of its co-founders, this is achieved through OSE’s series of public events and workshops. But should this model be approached with caution? In 2010, the government saw fit to introduce the Ebaac and slash England’s Arts Council budget by 30%, two policies which, it has been argued, exemplify an ideological undermining of the value of the arts within an economy that privileges monetary profit and tangible outcomes (Editorial AM364). Can OSE’s long list of quantifiable outputs be read as a result of the current pressure to make the economic case for art? And, if so, does this model, by emphasising education’s value by demonstrating its beneficial impact through the engagement of its neighbouring east London (now Margate) populace, reinforce art education as a resource that is no longer available to all, but is instead only accessible within an economy of exchange – whether it is financial or through cultural labour – as in OSE’s case? This is just one of several alternative interpretations that occurred to me while reading the book, critical narratives that would require an unaffiliated voice.

Sam Thorne, School: A Recent History of Independent Art Schools, Sternberg Press, 2017, 384pp, £21, 978 3 965791 81 9.

Lauren Houlton is a curator and writer based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 415: April 2018.