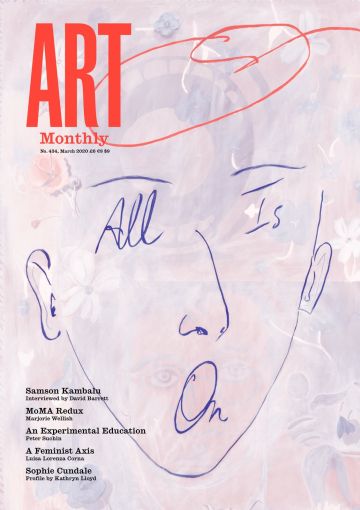

Profile

Sophie Cundale

Kathryn Lloyd examines the London-based artist’s new work, which takes on Greek mythology, cinema and the world of boxing to address long-term concerns about loss and trauma.

Sophie Cundale, The Near Room, 2020

In boxing, there is a move called the clinch. Capturing an opponent’s arms under their own, the boxer rests their forehead on the other’s shoulder, holds tight and exerts all their weight. Visually, it is akin to falling asleep on someone so heavily that you cause them to stagger backwards, the extremity of your exhaustion suddenly weaponised. The motivation for this move is two-fold: when the boxer is so tired they need to rest, or when trying to stop the momentum of an onslaught from their opponent. It is a survival tactic – to try to reset the balance, to regroup when you have no other choice, whether the attack is coming from your own body or someone else’s.

When this move happens in Sophie Cundale’s new film commission The Near Room, 2020, its interdependence is exaggerated. The two boxers fold over each other like children collapsing, exhausted after play. The arc of their worn-out bodies creates a frame for mutual surrender. But, seconds later, one falls to the ground after receiving the knockout punch and the match is over. The boxer’s voice-over narrates his own failure: ‘You’re slower than you were. So, they sense they’re getting close. Mouth and guts call for a split second of the other world, as your bodies connect in mock death.’

This scene is indicative of the themes that permeate Cundale’s filmmaking practice. Although her three major films to date – Prologue, 2013, After Picasso, God, 2016, and The Near Room – differ markedly in style, they are described by the artist as a trilogy of sorts. Over the past seven years, she has used film to explore the liminal, altered states that can arise around moments of flux, chaos, ecstasy and crisis. At times probing her own personal history and trauma to an unnervingly open degree, Cundale’s films have interrogated her experiences of grief, heartbreak, love and disorder. Always straddling the line between fiction and reality – although never verging on documentary – they tend to include the same network of collaborators, made up of friends and family. Cundale’s own presence in her films has been through a range of iterations. Across the trilogy, she is first presented as a directorial voice, occasionally bringing her head or hands into shot. She then moves into a lead role before, most recently, not being present at all. This trajectory is one that mirrors the artist’s modes of engagement: from provocation to embodiment to a reflection on the aftermath.

The Near Room marks the biggest change in scale and approach for Cundale. Here, the cast is made up of actors, professional boxer John Harding Jr, coach Mark Tibbs and artist Penny Goring. The production is noticeably larger-scale, the cinematography taking on the glossy saturation of a Netflix drama. Informed by the structure of Greek tragedy and the giddy melodrama of soap opera, her narrative weaves together two worlds – that of the characters the Boxer and the Queen. After his near-fatal concussion, the film follows the Boxer’s recovery. In hospital, he is examined and probed by doctors and boxing professionals alike: as a body and as a commodity. As he is tested, waiting to hear the viability of his future, his disorientations become entangled with the story of the Queen, who appears to be imprisoned inside her own kingdom.

While the Boxer exists in a clinical, contemporary world, the Queen’s world is an unnamed, hospitalless age of bedpans and candles. She is suffering from Cotard delusion – a rare syndrome in which the patient believes they are dead or in the process of dying. Her body has started to follow her brain: her teeth are falling from her gums, her hair is coming out in clumps, she can taste her body’s ‘own putrefaction’. The Queen is played by Goring who delivers her lines with a sort of maniacal detachment. Although the Queen and the Boxer are separated by hundreds of years, around them cast members double up roles, appearing across the threshold of time. But for these two – lovers who have never met – the distance is insurmountable. As the Queen commits to the delusion of death in her world, the Boxer commits to the illusion of life in his.

The film’s title is a reference to Muhammad Ali’s description of a hallucinatory place he would enter when he reached near-breaking point in the boxing ring. Describing it in vivid detail, Ali recalled a room with blinking neon lights, bats blowing trumpets, alligators playing trombones and snakes screaming. Cundale’s dual narrative draws on the transitory nature of Ali’s invention – a device which allowed him to decide between entering into or walking away from danger. As a long-term spectator of the sport, Cundale is interested in the theatricality of boxing. After the adrenaline of their performance, what do boxers turn to? When they can no longer box, what replaces the encounter with mortality they entered into every day? The film’s two protagonists are both caught in states of limbo, experiencing continual death in their own ways. For the artist, who watched as her father died and witnessed someone close to her enduring the UK’s psychiatric care system, these constructed worlds articulate the oblivion of the aftermath. Again and again, Cundale returns to the act of experiencing something life-changing and then waiting for life to change – for the world to realise that it has flatlined and everything is different.

If The Near Room is rooted in the ‘afterwards’, then After God, Picasso is concerned with the present moment. Made directly in the wake of her father’s death as well as the end of a significant relationship, it is Cundale’s most exposing piece of work. Here, she plays the key role opposite friend, actor and hypnotist Nicholas Audsley. The film follows a woman who visits a hypnotherapist ostensibly to get rid of her addiction to smoking. The majority of this 42-minute film takes place during their session, cushioned by events in her daily life – a visit to the nail salon, a party – and flashbacks to real-life footage of her and her ex-boyfriend. As she lies on the couch, her artificial nails freshly affixed and painted dark green, the hypnotist recounts the story of Pablo Picasso and his lover Dora Maar. Playing on the seduction inherent in hypnosis, After God, Picasso is an exercise in chemistry. As the film progresses, the bodies – both present and imagined – become more intertwined. While Cundale’s own grief merges with Maar’s, the state of hypnosis brings them together in a type of ridiculous exorcism. Cundale, mute and wide-eyed throughout, edges towards release: from smoking, from love, from people who have left.

Against this backdrop, one might view the title of her work Prologue ominously, the film coming as a precursor to the artist’s loss in After Picasso, God. Although she is only visible in the film through her interjections and instructions, her presence is palpable throughout. The action is seemingly mundane, following a couple as they embark on a weekend away in a caravan. They bicker over directions and get lost; they disagree over cooking in the kitchen with the awkward familiarity of people who haven’t been dating long. In fact, the boyfriend here is Cundale’s own, who she cast alongside an actress to play his on-screen girlfriend. She constructs and directs the intimacy between them, acting out the sort of anxiety and jealousy usually reserved for a circling mind. The lines are blurred between acting and genuine desire. Cynically prodding at her value systems of self-worth and infatuation, Cundale tests the limits of her relationship, ultimately prompting its inevitable breakdown. It is unsettling but comical, compulsive viewing – a mode which, although not yet present in the handheld camera work, is a nod to her affection for television and cinematic entertainment.

Through their intimate explorations, Cundale’s films allow for forms of release. Hanging on a central image or frame, they often return to the perpetual suspension of loss and grief. She is uninhibited by a delineation between private and public, throwing herself into the voids created by absence. In her worlds, truth, fiction and history converge, revolving around central, human issues that we will continually return to. Like the clinch, we’re often just resting on each other, waiting for someone to give in.

Sophie Cundale’s The Near Room is at South London Gallery from 6 March to 19 April 2020.

Kathryn Lloyd is a writer and editor based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 434: March 2020.