Feature

To Boycott or Not to Boycott?

Dave Beech asks the question

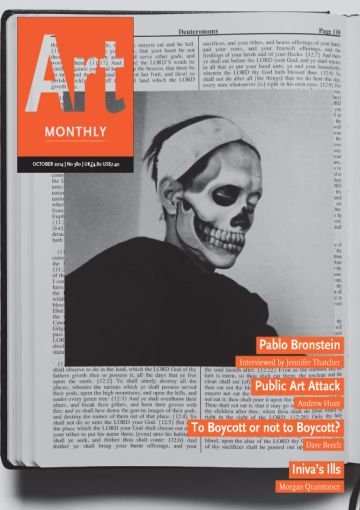

Liberate Tate, The Exorcism of BP, 2011, Tate Modern, London. Liberate Tate invited Reverend Billy and the Church of Earthalujah lead a mass exorcism in Tate Modern Turbine Hall over the ‘taint’ of BP sponsorship.

‘When nothing is happening the ideological state apparatuses have worked to perfection.’ – Louis Althusser

Boycott the Sydney Biennial! Boycott Manifesta 10! Withdraw from the Whitney Biennial! Protest against the corporate sponsorship of Tate by BP! Protest against the Dia Art Foundation’s retrospective of Carl Andre in honour of the late Ana Mendieta! Boycott all art materials suppliers in the name of art’s ‘dark matter’! Boycott the Creative Time exhibition! Campaign against unpaid internships in art’s institutions! Boycott! Withdraw! Protest!

Thirty years of conspicuous apathy and professional cynicism in the art world appear to have come to a glorious end. Political protest has reasserted itself in public acts of dissent, direct action and speaking truth to power. Although art’s funding, management and links to business and the state have been subject to scrutiny by artists on and off since the formation of institutional critique in the 1970s, the current mode of art’s political critique has become more general and more activist. Individual artists and isolated art groups have withdrawn from exhibitions for various reasons in the past (Art in Ruins had a reputation for pulling out of exhibitions as a matter of principle), but the current spate of art boycotts is rooted in a genuine political turn.

In its announcement to withdraw from Manifesta 10, Russian art collective Chto Delat? (What is to be done?) said: ‘Manifesta has shown that it can respond with little more than bureaucratic injunctions to respect law and order in a situation where any and all law has gone to the wind. For that reason, any participation in the Manifesta 10 exhibition loses its initial meaning.’ Meanwhile, under the slogan ‘Don’t Add Value to Detention’, 92 artists boycotted the 19th Sydney Biennale, which resulted in the Biennale severing links with its chief corporate sponsor, Transfield, which operates refugee detention centres off the Australian mainland (Artnotes AM375).

Judith Butler, Lucy Lippard, Chantal Mouffe, Walid Raad, Martha Rosler and Gayatri Spivak, alongside over a hundred others, added their signatures to an open letter calling on participants to withdraw from Creative Time’s ‘Living as Form’ travelling exhibition because one of its venues is an institution with a ‘central role in maintaining the unjust and illegal occupation of Palestine’. Allora & Calzadilla, Ultra-red, Women on Waves, Basurama, Celine Condorelli & Gavin Wade, Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency, Chto Delat? and US Social Forum subsequently announced their withdrawal.

The art boycott has established itself as a political device for calling institutions, corporations and the state to account. We don’t imagine museum directors, CEOs and heads of government retreating to their underground bunkers, but for them the art boycott is certainly unwelcome. The art boycott is a political act. If the laundering of corporate brands through art sponsorship entails the repression of a damaging corporate narrative – and its substitution by a fantasy narrative – then the boycott holds the threat of the unconscious. Or, if art institutions are the perfect medium for ideology, in which material practices are displaced with high ideals, the art boycott confronts ideology with the social reality that it misrepresents.

All boycotts have political or ethical agendas, but what exactly is the political anatomy of the art boycott? The art boycott combines qualities of the consumer boycott with the industrial strike and it puts anti-art in the proximity of the refusal of work. Undeniably, the art boycott fuses the politics of art with political activism generally, not only in its technique, which is used by both, or its content insofar as the art boycott tends to respond to the political circumstances surrounding an exhibition, but primarily in their shared historical constellation.

The political revival of the boycott, in calls to boycott goods from Israel for its violent occupation of Gaza and the short-lived campaign to boycott Lawrence and Wishart for withdrawing free online access to the complete works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, belongs to the tradition of consumer activism. Iris Marion Young constructs a conception of political responsibility that advocates the boycotts that ethical consumers, initially students, developed in the late 1990s, as a form of political activism. The key idea here is that ‘a transnational system of interdependence and dense economic interaction’ is the objective ground of an expansive moral responsibility. This sense of ethical obligation pervades the new tendency in art boycotting and the revival of the political boycott.

The art boycott resembles the industrial strike insofar as its act of absenteeism is intended as a coercive measure, but is unlike the industrial strike insofar as the withdrawal of labour has a direct impact on productivity and profit. The art boycott borrows its technique from the consumer boycott, a combination of non-participation and public announcements that specify preconditions for re-participation, but focuses on supply rather than demand. Informed and spurred on by the Italian Autonomia movement’s promotion of withdrawal, the art boycott is not principally associated with the withdrawal from work but the withdrawal of participation, in which participation is understood to be charged with ethical consent.

Despite the fact that boycotts withdraw from sites rather than take them over, the art boycott derives its political character – and its momentum – from the Occupy movement. It belongs to a political landscape that was redrawn by the Arab spring of 2011, which ushered in new modes of political organisation across Europe and the US, especially through the implementation of new techniques for political activism. The Spanish ‘indignant’ protests, also known as 15M, were the first of the new movements. They inaugurated a new mode of mass political protest based on occupations that reached decisions with consensus-based procedures, and they initiated a new icon for protest by wearing the Guy Fawkes masks now associated with Anonymous.

Occupy Wall Street, and the global Occupy movement that followed, was consciously modelled on this Spanish prototype, spreading its techniques and norms back across the world from whence it came. Occupy describes itself as ‘consensual, non-hierarchical, and participatory self-governance’, not merely asking the state to be more democratic but ‘literally laying the framework for a new world by building it here and now’. The theory of Occupy was already split by 2012 between hyperbole and disappointment. Noam Chomsky observed that the movement no longer occupied small tent camps but ‘now occupies the global conscience’ in the form of a ‘message spread from street protests to op-ed pages to the highest seats of power’. Peter Osborne deflated the utopianism of this quick transition of Occupy from political activism to a ‘symbolic’ event by characterising Occupy as the protest of ‘powerlessness and refusal’ which, he argued, ‘places it in a social space related to, yet institutionally distinct from, art’.

If Occupy and the boycott are alike in being largely symbolic, then artists will tend to feel that these forms of protest speak their language. However, in some instances Occupy has exceeded the symbolic and overshot its horizon of powerlessness and refusal. In June 2011, for instance, a group of 80 actors, artists, workers and citizens occupied the Teatro Valle in Rome to protest against the threat of privatisation from Rome’s city council. Three years later, the occupiers have successfully run the theatre while experimenting with new models of cultural management based on the notion of the bene comune (common good), and the occupation has spread to other theatres.

Slavoj Zizek declares that the ‘great revival of protest’ after the Arab spring consists ‘not [of] proletarian protests, but protest against the threat of being reduced to proletarian status’. As part of this argument Zizek misdiagnoses both the UK student protests of 2011 and the Tottenham riots, arguing that the former was a concerted effort of bourgeois youth to protect its privileges and the latter was nothing but an affirmation of consumerism. First, the students confronted neoliberal policies to increase fees that would deter all but the privileged from attending university; it was the coalition government that was attempting to reinstate the old privileges of higher education. Second, it makes no sense to see looting as conforming to the capitalist Utopia of market exchange: consumption without exchange, without purchase, is simply not capitalist.

However, if there is an element of truth to Zizek’s class analysis of the revival of protest – including the art boycott – then it is as a carrier of conformism and complicity even while it stands up against governments, corporations and institutions. Chomsky is not wrong to say that ‘the Occupy movement is the first real, major popular reaction that could avert’ the effects of neoliberalism and globalisation that have been hegemonic for over 30 years, but this does not prevent contemporary protest from being, in part, an outlet for privilege. Accordingly, the art boycott, which often speaks up for the disempowered and despairing, is the province of privilege. If consumer boycotts hand over more political agency to the wealthy, art boycotts hand over political agency to a minority of successful artists.

Nevertheless, artists who boycott large survey exhibitions represent the first serious challenge to the rise of the curator and the corporate sponsor that has shaped the neoliberal art institution. Putting aside the content of each boycott, therefore, we can say that the art boycott generally is a method for renegotiating the balance of power within art. The art strike was too general to threaten specific institutions and specific curators whereas the Yams Collective, for instance, which withdrew from the Whitney Biennial in protest against the alleged racism of the curatorial selection of artwork, points fingers, names names and calls for actual reforms (Artnotes AM377).

The boycott resembles the ‘block’ gesture, one of the General Assembly hand signals used in consensual discussions. Signified by folding your arms over your chest in the shape of a diagonal cross, the block is the most extreme of the GA gestures. ‘It indicates a serious moral or practical objection to the proposal,’ in the words of the Writers for the 99%, ‘indicating that the objector will leave the group if her or his concerns are not addressed.’ The block has more power than the boycott, however, since it acts as a veto, whereas the individual boycott alters the composition of an exhibition, or perhaps forces the resignation of an individual, without bringing the whole thing to a halt.

Pushing in the opposite direction of the art boycott, power occasionally withdraws from political confrontation. One example of what we might call the inverted boycott took place when the organisers of the 13th Istanbul Bienal cancelled the public programme out of fear that these events would become targets of the popular protest that had gripped the city. In another variant, institutional critique reverses the ethical charge of the boycott, using it as a rationale for participation rather than withdrawal. Andrea Fraser explains: ‘From the vantage point of institutional critique, I define criticism as an ethical practice of self-reflexive evaluation of the ways in which we participate in the reproduction of the relations of domination.’ So, ethics allows participation in an institution by providing subjective compensation for an objective predicament. Following the example of institutional critique rather than the art boycott, Liberate Tate stages protest events actually within Tate, dissensually participating in, rather than withdrawing from, the institution. Justifying its entry into the museum by the fact that it is normatively opposed to Tate’s objective economic entanglement with BP, Liberate Tate is more fleeting than Occupy and more embroiled in the institution than the art boycott.

Occupy takes over a place through ethical self-organisation; institutional critique participates in an institution through ethical practices of critique; and the art boycott is ethically obliged to withdraw from institutions. The art world has a highly attuned sense of art’s complicity with social forces, and a poorly attuned sense of art’s role in the broad political struggle. The art boycott satisfies both of these conditions by conducting its site-specific activism by absenting itself. Paradoxically, the boycott takes a stand by standing off, which raises the question of whether it is an example of activism or inertia. Is the boycott an instance of ‘nothing happening’ or is participating in controversial exhibitions better understood as nothing but business as usual? Indisputably, if the boycott is a political act, then this is a formalist politics to which the artwork’s content or specific properties cannot contribute. And if participating in exhibitions is necessarily to comply with its objective institutional form, then this too amounts to a formalist politics that condemns the work regardless of its actual material and semiotic qualities. And this is why the art boycott obtains its highest justification when the content of the artwork appears to be nullified by the political circumstances of its institutional display.

There is an assumption at large within the arguments against art events in trouble spots that art is nothing but a luxury item or must always be affirmative. Art Against Cuts is a good example. To coincide with the strike on 30 June 2011 by teachers, lecturers and other public-sector workers, the group called for artists and other cultural workers and administrators ‘to suspend all cultural programming/work’. This is an example of a proposed boycott by artists and others that is more closely aligned to the industrial strike than the current spate of art boycotts. While it would be absurd to boycott political protest (ie to withdraw direct action because a situation is indefensible), it appears far from absurd to boycott art (ie to withdraw participation in an art exhibition because a situation is indefensible). Rather than see art as an active agent within political struggle, or even acknowledging that every political struggle must also be a cultural struggle, the art boycott dovetails with the idea that art’s only mode of participation is complicity.

Some of the philosophical niceties about action and inaction called up by the art boycott appear to be undecidable, at least at the level of generality in which we speak of the art boycott as such. However, the problem that the art boycott cannot fully shake off is that insofar as it focuses on a particular issue – arms dealers, gay rights, gentrification etc – it implies that the institution under normal circumstances is unobjectionable. Boycotts are atypical, which is the reason why they can call attention to specific institutional deficiencies and, therefore, are ill-equipped to tackle general and deep-seated conventions and structures common to all art institutions. Do not boycotts affirm all those institutions not included in the specific boycott? Is it not difficult to get away from the idea that the art boycott, in singling out particular exhibitions and institutions for active inaction, covertly expresses the message that everything (else) is alright?

The art boycott can be politically aligned to the cultural occupation, but they are tactically distinct. Akin to worker takeovers, in which unprofitable facilities under threat of closure become worker- and community-owned firms that flourish under worker management, the occupied theatres go further than the art boycott’s ethically charged abstinence. The point is not that the boycott is negative and the occupation is positive but that the illegal occupation is a strong negation of the status quo. The difference in principle is that the boycott is limited by the horizon of protest while the occupation can be engaged directly in the process of political transformation. In politics, however, principles can be outflanked by events.

Prior to its announcement to boycott Manifesta 10, Chto Delat? had explained that it was opposed to the art boycott, especially in Russia where ‘a cultural blockade will only strengthen the position of reactionary forces’. Instead of boycotting Manifesta, Chto Delat? hoped, as a local collective, to occupy the role of ‘alternative hosts and representatives of the city’. As the Manifesta curator, Kasper König, sought increasingly to marginalise any political disruptions emanating either from the state and its discontents or from participating artists, Chto Delat? decided that its original hopes would be thwarted by the circumstances under which they would be staged. Remaining in principle against the boycott, the group boycotted Manifesta under duress. Despite its limitations, therefore, the art boycott is a technique for reinstating political dissent at the heart of hegemonic complacency.

Dave Beech is an artist in the collective Freee.

First published in Art Monthly 380: October 2014.