Feature

TV Makeover

Colin Perry on the vexed relationship between art and TV

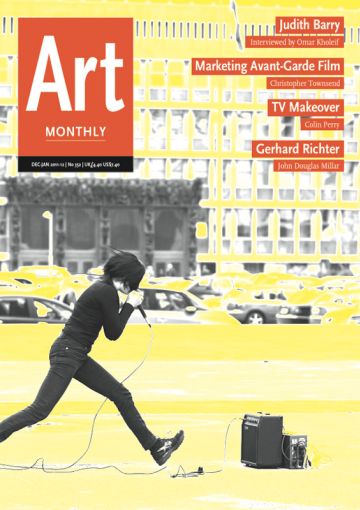

Stuart Marshall, Bright Eyes, 1984

Television has once more become a fashionable subject within artistic practice and discourse. But how do the two forms of image production – art and television – relate to one another? Is the relationship one-way or reciprocal? Does television always come out on top? In order to untangle the issues involved, we need to look to the history of video art. Video art has a long history of engaging with television, but the methods adopted by artists in approaching this daunting medium have been varied and even contradictory. Over the past 50 years or so, reflections on television by artists have tended to veer towards one of three basic categories, which we could define as ‘autonomy’, ‘parasitism’ and ‘activism’. The first approach adopted by artists in the 1960s and 70s utilised Marxist-inflected critiques in order to disrupt the medium’s perceived distortion of phenomenological life while also making claims for art’s aesthetic autonomy. Whether shown in a gallery or broadcast on national or local cable television, such works highlighted TV’s physical properties in order to assert the primacy of lived experience over narrative and spectacle. In the second approach, first adopted in the 1980s and still predominant today, the relationship slowly became less antithetical. As mainstream television in the 1980s began to schedule regular slots for video art (usually of a few minutes or seconds), art was effectively ghettoised from mainstream programming leaving the latter largely unaffected. In such a relationship, video art shown on TV operates not as a critique but rather as a promotional device for individual artists (the channel in return may glean some highbrow kudos). In turn, it is also possible to say that much video art today uses kitsch or retro tropes from television within a setting for marketing purposes alone – such art gives little or nothing back to television itself and has little or no claim to understanding its hold over contemporary life.

A third category of artistic engagement with TV tells a different story. Activist video and film practitioners have long sought to draw viewers’ attention to television’s least savoury tendencies (stereotypes of race and sexual orientation, for example), and have worked hard to realise alternative visual expressions that might present a vision of society open to plurality and tolerance. Over the past 30 years such approaches have in fact been quite successful. Television, as we see it today, has been partly defined by the activities of campaigning video and film artists from the 1970s, 80s and 90s, who laboured hard to shift mainstream visual culture from a monolithic entity of normative cultural codes to one in which plurality, difference and fragmented identities are socially acceptable. The trend is woefully undocumented. In this article, therefore, I aim to draw some examples to the fore.

Perhaps activist videomakers’ most conspicuous contributions have occurred in the US, with the emergence of community access TV (CATV) groups such as TVTV (several of whose members also belonged to the art collective Ant Farm), Videofreex, Raindance Corporation and Paper Tiger Television Collective who created an alternative world of ramshackle programmes focusing on issues including identity politics, media ownership and sexuality. TVTV in particular had an impact on other broadcasters with The TVTV Show, 1976, and The Bob Dylan Hard Rain Special, 1976, both co-produced with NBC. But it is works such as their classic Lord Of The Universe, 1974, that shone some much needed light on the Guru Maharaj Ji cult and their droll disassembling of media reportage of the 1972 Republican National Convention in Four More Years, 1972, which are the more acerbic.

In the UK we can also see some definite examples of the impact of art and activist film and videomaking on mainstream broadcasting. Channel 4 was established in 1982 by an act of Parliament explicitly to cater for the UK’s previously marginalised audiences (first- and second-generation immigrants, countercultural youth, Welsh and northern audiences), with the further remit to ‘encourage innovation and experimentation’. It was to draw much of its footage from independent producers – including artists – and was responsible for co-establishing and supporting a huge network of workshop groups for independent and black film and videomakers (for example, Amber Films, Black Audio Film Collective, Sankofa Film and Video, Retake Film and Video and Red Flannel Productions). In line with this broad and radical remit, Michael Kustow, the channel’s first commissioning editor for arts, wanted to challenge the public with a range of programmes that ‘mixed genres’ which, he argued, would ‘wrong-foot people into illumination’; he further argued that the channel would ‘let art shape television, not vice versa’. Radical early programmers were vital to this support: one such was Rod Stoneman, a filmmaker who is perhaps most famous now for his remarkable documentary Chávez: The Revolution Will Not Be Televised of 2003.

The channel acted on its words: it broadcast Black Audio Film Collective’s Handsworth Songs, 1986, a lyrical disassembling of the causes of recent riots in Birmingham and London; Michael Clark and Charles Atlas’s Hail the New Puritan, 1985-86, a deliciously camp ‘pop-ballet’; and Stuart Marshall’s Bright Eyes, 1984, one of the first full-length documentaries to confront the AIDS crisis and the media hysteria surrounding it. Artists such as Marshall and Isaac Julien presented forms of experimental film and meta-criticism rarely seen on British TV before or since. Artists also helped give voice to views the other channels were assiduously avoiding. Notably, Channel 4 supported the production of The Miners’ Campaign Tapes, 1984, a series of videos made with union support by filmmakers and artists including Mike Stubbs, Roland Denning and Chris Rushton, footage of which was apparently broadcast on the channel’s relatively sympathetic reportage of the strikes.

Why has our communal memory and art history so roundly overlooked this strain of artistic practice and its real-world influence? One reason, perhaps, is a sense of failure: artists have stopped trying to change television, and for good reasons. In the early decades of video art, there was much hope that TV would prove an open and democratic platform for visual art, but the actual experience proved rather different: attempts to intervene in the ‘flow’ of programming played easily into the hands of programmers looking for cheap means of filling up airtime. While Scratch Video in the 1980s sought a critical neo-Dada visual overload, this was easily absorbed into television’s new-found lust for sharp, snappy and ironic juxtapositions. Often, artists who should have known better played right into the trap. In 1971, David Hall was commissioned by the Scottish Arts Council to produce TV Interruptions for national broadcast. Screened without announcement between programmes, viewers’ screens would suddenly appear to fill with water or burst into flames. However, Hall’s work was co-opted with his own blessing when, in 1993, he remade TV Interruptions for MTV. Screened within the context of the channel’s own disruptive music clips, the work became just more visual fodder.

Criticism, parody and deconstruction are easily negated by the way in which a work is contextualised: TV presenters, for example, might appear before or after the broadcast of an artist’s video in order to ‘explain’ its unruly format. When artist Nathaniel Mellors recently produced an introductory video for David Dimbleby’s 2010 series The Seven Ages of Britain, the presenter intervened in the final cut to explain that Mellors’s video seeks to ‘make a comment on the role of television in modern society. Whatever you make of it, it shows how much art has changed in the last hundred years’ (my italics). Such caveats effectively remove the bite from an artist’s work. Another element in the demise of cultural-critical responses to television emerges from a prevailing view within discourse that TV has lost its negative powers over individuals and society. We are now its ‘users’ since we can choose what to watch when we want with TV-on-demand or via the internet. In the digital world, other viewpoints are a mere Google click or two away; we can all add commentary and feedback to world events from the comfort of our own laptops. But it should be recalled that television’s power has not waned and – conversely – the internet has widened its potential reach: a TV station broadcast from an undemocratic country (Al Jazeera in Qatar) has played a huge role in the Arab Spring; and in the US, the Murdoch-owned Fox News channel partially defines that country’s political framework. (A recent poll by Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey found that Fox News viewers are less well informed on current affairs than those who don’t watch any news at all.)

Behind this everyday relativism – my view has equal weight to a newscaster’s – is a theoretical blindness to social reality, the fact that most people still watch a great deal of the small screen. However much we draw on the views of affective ‘everyday practice’ in Michel de Certeau’s writing, and Jacques Rancière’s theories of auto-pedagogy, the fact remains that viewers are actively choosing to view images they have little control over. In an infamous diatribe (On Television, 1996), French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu gives relativistic views short shrift: ‘Facility with the game of cultural criticism is not universal … Anyone who thinks otherwise has simply surrendered to a populist version of one of the most perverse forms of academic pedantry.’ Indeed.

In some ways, of course, critics of activist-artistic involvement in TV are quite correct. Channel 4’s early ‘golden years’ were soured by an elitist attitude towards its audience – the Sun newspaper drolly called it ‘Channel Bore’. Its increasingly sensationalist use of otherness as a spectacular form of voyeurism is also deeply problematic. Channel 4 might have changed broadcasting in the UK, but by the 1990s it was clear that, while TV had gained a sense of inclusiveness, it had lost much of the Reithian notions of pedagogy and the public good. Battles were won but the war was lost: utopian calls for participation and representation had created Big Brother and The Only Way is Essex. It has also become increasingly clear that such programmes came at the expense of incisive or original political reportage. By the late 1980s leftist media analysers had come to theorise ways in which the broader field of journalism might be not a bulwark of democracy but rather a fundamental barrier against it. In the US, Edward S Hermann and Noam Chomsky, Robert W McChesney and Ben Bagdikian put forward the view that media monopolies were killing television and newspapers by substituting fluff for in-depth analysis, with dangerous consequences. By the mid 1990s, Bourdieu was analysing a situation in which media activists were struggling to ‘keep what had become an extraordinary instrument of direct democracy from turning into a tool for symbolic oppression’.

Extending this analysis towards artistic practice, critic and theorist David Joselit, in Feedback: Television Against Democracy, 2007, adopts a melodramatic register: ‘art stands against television as figure stands against ground, and television, in its privatisation of public speech and its strict control over access to broadcasting, stands against democracy.’ Yet, for all the strengths of these analyses, a robust history of art-activist broadcasting initiatives might provide examples of how television can contribute to an enriched and complex society.

With major exhibitions devoted to the subject, including curator Chus Martinez’s ‘Are you Ready for TV’, 2010, at MACBA in Barcelona, ‘Changing Channel Art and TV 1963-1987’, 2010, at MUMOK in Vienna, and a recent series of ‘broadcasts’ by Auto Italia Southeast and Lucky PDF in London, it is evident that television has become at once a subject to be analysed and a voguish object of nostalgia. But there appears, so far, little commitment to examining television’s public role and its potential to change and be changed. For example, in a panel discussion at this year’s Frieze Art Fair titled ‘On Television’, the focus was largely on issues of taste. One commentator argued that programmes such as The Wire and Curb Your Enthusiasm constitute the most ‘vital’ art form of our times, and other participants were keen to put forward their own nominations for a canon of ‘New Television’ (which largely centred on the products of the US station HBO, producers of The Wire et al). Thankfully, executive producer at BBC Arts Jonty Claypole was able to provide some concrete historical counter-examples to suggest that these series were merely high-end versions of a trend seen in much earlier series in non-US countries (the BBC’s I Claudius, 1976, being a prime example). More fundamentally, of course, these arguments are unhelpful in providing any insight into the place of television in society and its affective powers. The pressing issue is not whether Mad Men is a good enough product to be considered as art or literature, but rather how we might analyse its social or psychological effects – the critic’s taste is not the important factor.

This was precisely the point put forward by Theodor Adorno in How to Look at TV, 1954, a text that analyses the coded support of the status quo in McCarthy-era TV. Adorno’s analysis of how the ‘rigid institutionalisation transforms modern mass culture into a medium of undreamed of psychological control’ might be an overstatement, but it points to a key reason why television has mattered in the past and continues to be of importance today.

One final question must also be faced. In Bourdieu’s terms, the battle over television is not so much over democracy as over the autonomy of specialist fields. He argues that when individuals with a deep knowledge of and authority in art, science or sociology appear on the small screen, they must adapt to its norms: give quick-fire answers, concede to a motion ‘for’ or ‘against’ and provide an answer to even the most absurd questions. Worse, they are forced to justify themselves not according to the rigours of their field but to the demagogic reign of broadcasting. When art seeks to justify itself according to television’s value system, we might say that its autonomy – by which we mean its own value system – has been compromised by a parasitic relationship towards a dominant medium. Arts journalism (this article included) and critics must likewise not be excused. Often, when a critic appears on television, it is not to make a serious point about art; it is to draw attention to his or her own cultural eminence and to ask for his or her opinions to be vindicated by a non-specialised audience that may be deeply antipathetic towards the very subject he or she is discussing. But these will be exceptions to the rule.

The demagogic appeal of television can bleed into the heart of art criticism off-screen: when critics champion The Wire as art, it seems likely that they are seeking to draw the symbolic power of that programme towards themselves rather than make a serious point. As artists, critics and commentators look once more to relate to broadcast media, it is vital to recall how deeply problematic the medium remains, and why it was the target of activist artists in the first place.

Colin Perry is a writer and critic.

First published in Art Monthly 352: Dec-Jan 11-12.