Feature

Art and the Chthulucene

Jamie Sutcliffe takes a worm’s eye view

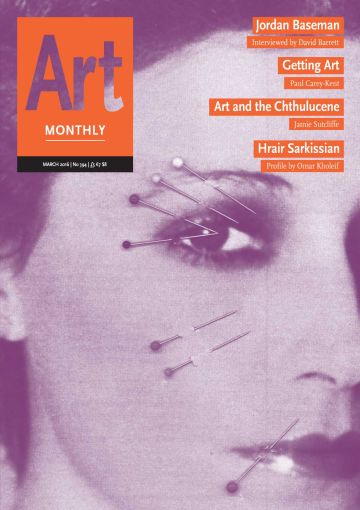

Mark Peter Wright, I, the Thing in the Margins, 2015

Naming the present age as the Anthropocene in order to acknowledge human impact on the planet merely perpetuates the hierarchical separation of Homo sapiens from the rest of the biosphere. Do artist and anthropologist Zoe Todd, bio-artist and ‘gene-tinkerer’ Eduardo Kac, and arterial thinkers Anna Tzing and Donna Harraway offer useful alternatives?

The Anthropocene, like the image of a continuous carbon-tarnished substrate that it all- too-easily conjures, is a platitudinous veneer. It extends beyond the crust of an infected Earth into a universalising concept that is in dire need of differentiation. In fact, let’s keep within the geothermal register and make that ‘decomposition’ – the Anthropocene needs to be composted.

Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoemer’s proposition that we are living in an unprecedented age of irreversible anthropogenic impact provides a neat narrative for the popular mobilisation against the stagnancy of conservatism, industrial interests and outright denial, but we haven’t yet adequately addressed how the Anthropocene has been ideologically constituted and distributed, and what bodies it seeks to implicate in its supposed ubiquity. We may exist on the same planet, but we certainly don’t all share the same experience of climate change.

In an urgent 2015 paper entitled ‘Indigenising the Anthropocene’, the artist and anthropologist Zoe Todd noted that the general framing of the term blunted ‘the distinctions between the people, nations and collectives who drive the fossil-fuel economy and those who do not’. When the narrative is smoothed into an all-encompassing paradigm, the residual damage of imperial and colonial infringements risks becoming lost in the collective obligation to act. Writing from the position of an indigenous person of Métis heritage, Todd suggests that the discursive monopoly of the term Anthropocene is unsurprising due to the ‘undeniably white heteropatriarchal space of a Euro-Western academy’ that either ignores, trivialises or recuperates indigenous knowledges that could contribute much-needed nuance to global dialogue. Todd’s proposed decolonisation of thought leads us to one of the main problems at the tender heart of the Anthropocene: the notion of the human as a negatively indexed position of commonality – we are all guilty.

Assuming human vulnerability as a species concern, the Anthropocene addresses the issue of ecological decline in terms of a unified world community. This idea of the human relies on tired tropes, including the Vitruvian centrality of ‘Man’ to the universe, and on the hierarchical subjection of nature to a technologically accelerated culture. This does not take full stock of the surreptitious processes through which biogenetic capital has, in the words of Rosi Braidotti, exploited ‘the generative powers of women, animals, plants, genes and cells’.

Writing in this magazine some months ago, Bob Dickinson provided a useful survey of artists’ responses to the current ecological crisis and asked whether gallery-based art or curatorial remits were equipped to shift public opinion in the dying biosphere – and, by hypothetical extension, whether they could even be considered to possess the required longevity to persist through the vortices of deep time (AM389). I think an essential precursor to these questions should be a challenge to the assumption of a hermetically defined species boundary, and to explore instances of cross-contamination and multi-species coexistence that de-centre the grossly falsified subject position currently pitched as a rallying-point.

In a striking example of species porosity, philosopher Timothy Morton raises the example of bio-artist Eduardo Kac, the Brazilian born gene-tinkerer who notoriously engineered a breed of bioluminescent rabbit, GFP Bunny, 2000, by transgenically appropriating cells from a hydrozoan jellyfish. Morton suggests that the shock of such an action might lie in the revelation that if one can do this to a rabbit, then there may not have been such a distinct thing as a ‘rabbit’ – or a ‘jellyfish’ – in the first place. Central to Morton’s ecological thought is the idea of ‘the mesh’, a reconceptualisation of human and non-human relations that refutes the hierarchical separation of Homo sapiens from its environment by drawing humankind down into a web of proximities, extending the phylogenetic linearity of the Darwinian tree of life into a network of nodal points through which ‘strange strangers’ might co-exist in a state of mutual interdependence. Morton provides some characteristically big images for thinking through our predicament, but I prefer the arterial ‘thinking-with’ of Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing and Donna Haraway that prompts considerations of emergent species-assemblages, always with a view to the complexity of nature-cultures in flux and with respect to the diverse organisms with which we share our own porous epidermal and ontological boundaries.

In her recent book The Mushroom at the End of the World, Tsing employs the figure of the matsutake – a delicate mushroom prominent in Japanese cuisine and prone to flourishing in areas of human-disturbed forest – to track the diasporic movement of Mien and Hmong communities from South China to the national parks of Oregon in the US. In a location uniquely suited to matsutake germination, she finds a rich triangulation of woodland clearance, fungal fruition and human enterprise that leads her to reject notions of species self-containment and to proffer instead the idea of contamination as a vital form of collaboration: ‘Collaboration is work across difference,’ she writes, ‘yet this is not the innocent diversity of self-contained evolutionary tracks. The evolution of our “selves” is already polluted by histories of encounter; we are mixed up with others before we even begin any new collaboration.’ For Tsing the forest-human-mushroom connection spurs a rush of troubled stories that aren’t reducible to a simple holism but instead suggest knowledge practices alternative to a teleological modernity, an entangled mode of thought more suited to splintered states of precarity.

Reading Tsing’s wonderful book and thinking through its challenges, I was reminded of a fractious situation in 2013 when, while addressing a conference on art and agriculture in the Lake District, curator Ute Meta Bauer introduced a project by Korean artist Jae Rhim Lee then titled The Mushroom Death Suit. This was an ambitious proposal in which mycelial spores were woven through a biodegradable funeral shroud that could potentially eliminate the transposition of bodily toxins into the earth through fungal purification. Despite the ecological validity of the garment – a perfect instance of collaborative contamination – it was met with an unusual disbelief and mild intolerance by the audience, as though its intentions were preposterous.

Haraway, meanwhile, has provided a necessary diversification of the Anthropocene with her suggestion of a plurality of story-generating approaches: the Capitalocene (originally coined by Jason WMoore to place capitalist exploitation at the centre of Anthropocenic enquiry), the Plantationocene and, most fittingly for this brief reflection, the Chthulucene. Summoning something, at least, of the gothic-fantasy author HP Lovecraft’s mind-destroying octopus god Cthulhu (note the spelling difference Haraway employs to sidestep any direct association with this notoriously xenophobic author), the Chthulucene stresses the tentacular interconnectivity of life-forces across species and cultures (Naga, Gaia, Tangaroa, Terra, Haniyasu-hime, Spider Woman, Pachamama, Oya, Gorgo, Raven, A’akuluujjusi), suggesting ‘webs of speculative fabulation, speculative feminism, science-fiction, and scientific fact’. While Lovecraft pitched the tentacular as a thought experiment in the cosmological displacement of humanity, Haraway takes inspiration from science-fiction author Ursula K LeGuin’s ‘CarrierBag Theory of Fiction’ in which stories become vital components in making kin, and for ‘telling the tale of still possible recuperation’.

Moving downwards, through the trite crust of the Anthropocene as a mode of thinking and into the messy sublevels of undergrowth and abyssal waters of the entomological, mycological and zoological domains is one way of providing a perspectival shift that generates stories capable of reconsidering species interdependency. It is an approach that has come to my attention in recent work by Rachel Pimm, Joey Holder and Mark Peter Wright, artists whose diverse practices engage speculative non-human worlds populated by challenging subterranean, subaquatic and subconscious critters.

In August last year I found myself strangely cocooned in a side room of the Chisenhale Gallery for Rachel Pimm’s worming out of shit, 2015, a spoken-word performance disquietingly enhanced by the sonic manipulations of archaeological sound designer Lori E Allen. With the tightly packed audience seated on large expanses of pastel-hued foam that were impossible not to pick at and break apart (fittingly reclaimed from The Brutalist Playground that had previously been installed at RIBA by Assemble and Simon Terrill), the artist relayed a monologue that was equal parts natural history, animist evocation and ecoparable. Beginning with an etymological excursion that sought to draw listeners through degrees of taxonomical classification down into the earth itself, Pimm tentatively enunciated a lyrical path towards the peculiar intestinal architectures of Annelid bodies: ‘Vermin? Worm. Or Verm? Vermi? Vermis – the Latin worm, the ancient, original worm, or the cerebral neural worm-shaped pathway that carries the sense of what one’s own body is, alongside and in relation to, and touching neighbouring things. Like a direct wormhole to stuff, to other matter.’

This was a sound-world of sinking velocities, all matter finding its way downward through processes of ingestion and decomposition, drawing connections between organic fecundity and the high-turnover simulations of competitive agribusiness. The worm was situated accordingly as a producer of ‘geo-paste’ in a genealogy of entropic agents including oceanic erosion, volcanic spluttering and tectonic movement – the ‘fine-finisher’ of a geological process in which arable soil matter was formed as the necessary prerequisite to mammalian surface existence. When the creatures were evoked en masse, Allen’s live sound manipulations seemed to multiply, layer, delay and heighten the pitch of Pimm’s voice, thereby creating the effect of a swarming multitude of interdependent entities caught within a mutually sustaining ecosystem of arthropodal bodies. It was striking to hear how effectively Pimm’s text could compel the listener to imaginatively inhabit the body of the worm while reflecting by analogy on the tribulations of human existence: the momentous scale of the rich mire of landfill dwarfing the insect body quickly became a daunting image of the human world overcome with non-degradable rubbish.

In his 2010 book The Ecological Thought, Morton introduced the term ‘hyperobjects’ to denote ontologically rupturing factors so massively distributed in time as to ‘burn a hole in our minds’. Such non-perishables, for example plutonium or styrofoam, will not rot by natural means in our lifetimes: ‘They do not burn without themselves burning (releasing radiation, dioxins, and so on).’ In taking us down into the polluted substratum of the contemporary landfill, or evoking the worm’seye view of a radioactive waste silo drilled into solid bedrock by Pangea Resources Ltd – the world’s foremost developer of subterranean nuclear waste storage – Pimm adopted multiple perspectives that extended a sense of precarity by empathic means into new habitats. Haraway has urged us to make kinship ‘symcthonically’, while also suggesting, in an amusing compound of companionship and our imminent situation of earthly relationality, that we are not necessarily post-human but ‘com-post’. The performance worming out of shit brought this strikingly to mind through an immersive weaving of tales.

While biologists Lynn Margulis and Dorian Sagan offered a late-20th-century counter-narrative to the idea of evolutionary intentionality by suggesting that planetary life had emerged haphazardly through the symbiogenetic merging of bacteria and other microorganisms, the impact of this revelation seems not to have found its way into the popular narratives we tell ourselves about the genetic constitution of the human – ie we are not stable closed systems but swarming microbial multiverses. Joey Holder’s tech-sublime video works that tessellate cellular wallpapers and neon-blasted bio-noir installations, postulate a dark but no less emancipatory form of symbiotic thinking through a jarring infographic address that sinks us firmly back into generative primordial pools. Watching her short infomercial trailer Dark Creatures, 2015, as part of ‘Exta.’ curated by Lucy A Sames and Dane Sutherland at Deptford’s Res. project space last autumn, or visiting any of her many research-laden websites, has left me feeling dizzied by a visual language that foregrounds the vertiginous immensity of endless mutational difference. Holder’s art is a sustained interrogation of species-othering, bringing techniques of visceral abjection, subaquatic alienation and zoological horror to the digital interfaces of social-media and 3D-imaging software, a weird matrix of soft bodies and virtual representations, deep-sea reconnaissance and insectoid diversity.

The collaborative exhibition ‘Lament of Ur’ with Viktor Timofeev at KARST in Plymouth last December used an alien motif to complicate understandings of biological determinism. By excavating an ‘ancient-astronaut’ theory that human life could be the product of an extra-terrestrial instrumentalisation of human labour power, the show pitched a potent allegory suggestive of contemporary fatalism in the face of perceived systemic dominance and exploitation. Holder’s accelerated pursuit of hybridity is a kind of riposte to taxonomic rigidity, and it is nowhere more visible than on her websites Mutagen, Biostat, Hydrozoan and Sushishhihuiiishii, which mine an abyssal seam of the internet’s weirdest creatures and biotech elaborations. Here, genetically enhanced greyhounds rub shoulders with vertical gardening projects, culinary crustacea and scrolling genomic code. Holder’s speculative moodboards seem to suggest that if the human phylum does survive the current age of extinction, it would look dramatically different from the way it does presently, an iridescent composite of patented machine parts and cultivated tissues.

From the earth, through the sea to the cryptozoological thickets of the liminal subconscious. Mark Peter Wright’s I, the Thing in the Margins, presented recently at IMT in London, summoned something of the spirit of Fortean cryptid Big Foot as she was memorialised in the infamous Patterson-Gilman hoax tape of 1967. As an archetype of a supposedly lost wild individualism, interest in the mythical figure of the Sasquatch logically correlates to periods of ecological anxiety in which the wilderness is perceived to be receding. Wright’s show addressed the paradoxical agency of the nature recordist, a character who is always enmeshed in their environment but prohibited from registering their own presence within the audio encryptions of their field documentations. In Humanimentical Prototypes, 2015-, a series of cyborgian microphonic constructs imagined a sentient technological organism capable of making its own autonomous recordings, while in Contact Zone #2, 2015, a minimal assemblage of speaker and camouflage-netting ventriloquised a collaged sound essay reflecting on the appropriation of indigenous North American tracking techniques by the pursuer of animal sounds aiming for as little sonic impact as possible. The disquieting centrepiece of the exhibition was Patterson, a totally embodied humanoid ‘microphone’ that may or may not have been responsible for the feedback that could be heard throughout the intensely green-lit gallery. Patterson raised some unsettling questions regarding the transitional space between worlds and species insofar as it provided an uncanny vector between human and non-human locales.

Ascribing agency to the non-human as an investigative strategy, these differing practices broach an interspecies threshold that could provide humbling conduits towards thinking against the complacencies of anthropocentricity. To borrow a phrase from anthropologist Eben Kirksey, they position us in a bustling multispecies community of ‘ontological amphibians’ that are becoming increasingly aware of each other, terraforming the Chthulucene for hyrbid subject-positions adequate to crisis.

Jamie Sutcliffe is a writer and publisher based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 394: March 2016.