Viewpoint

Art Investigation

Daniel Neofetou argues that Forensic Architecture’s success in the art world is symptomatic of a broader demotion of art’s capacity for political opposition

The research collective Forensic Architecture has been nominated for the Turner Prize, coming after numerous plaudits for the group’s recent exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London (Reviews AM416) and presentations at Documenta in Athens and Kassel last year. Emphatically and unambiguously siding with the oppressed, the collective has been hired by international prosecution teams, NGOs and political organisations for its meticulous empirical reconstruction of neo-imperial injustice meted out in the Middle East and elsewhere. While the political impact of Forensic Architecture’s investigations is often frustrated by the limits of the frameworks in which it operates, the group’s tireless efforts to lend voice to the voiceless in a legally persuasive way is vital.

In the face of the undeniable political urgency of this research, it may seem irrelevant or even reactionary to question whether the work of Forensic Architecture should be considered art. While this question was hotly debated in reference to Assemble, the architecture collective and (arguably) covert gentrifiers that won the 2015 Turner Prize, it might be claimed that all that matters is that Forensic Architecture will be receiving increased exposure. However, without detracting from its political importance, Forensic Architecture’s protest against dominant powers is qualitatively different from the protest against dominant powers of which art is capable. Moreover, the success of Forensic Architecture in the art world is symptomatic of a broader demotion of art’s own capacity for political opposition in favour of art as a conduit for often paraphraseable political content.

Theodor Adorno was wholly preoccupied with the way in which art does justice to the suffering perpetuated and ignored by capitalism, claiming that ‘hardly anywhere else does suffering still find its own voice’. However, he also wrote that art respects people ‘by presenting itself to them as what they could be rather than by adapting itself to them in their degraded condition’. The reason why these two propositions do not contradict each other becomes clearer if we understand why suffering finds its own voice in art for this inveterate Marxist. Adorno argues that this is because the experience of art concerns the non-conceptual particularity of subjects and objects which cannot be reduced to the bureaucratic rationalisation which dominates the world in the interest of private profit. The disregard by the latter of this particularity is why suffering abounds, but it would receive its due under changed conditions. This particularity, then, is non-conceptual in terms of prevailing concepts, but it is not irrational, and instead it anticipates a form of reason which would take account of particularity.

In a recent interview, Eyal Weizman, the founder of Forensic Architecture, makes a point of the fact that, contrary to the supposedly outdated notion of the artist’s mission as ‘the augmentation and radicalisation of sense perception’, his collective contributes fundamentally to politics on a ‘collaborative, networked’ level. Indeed, while Forensic Architecture provides a wealth of timelines, maps, digital reconstructions and video footage documenting specific results of dominant rationalism’s disregard for the particularity of human beings, the group does not seek to affect the viewer as an embodied subject dependent on other subjects and objects. Instead, the spectator is positioned as an omniscient surveyor on the right side of history. As Naomi Pearce writes in her otherwise positive review of the show for Art Agenda, Forensic Architecture’s installations ‘fail to harness the exhibition as a sensory experience’.

A limit-case for the argument that art’s political power lies in its particularity has been developed by the Adornian scholar Jay Bernstein in reference to Abstract Expressionism. Bernstein claims that, while the oppressed are not represented in, say, a Jackson Pollock canvas, this negation of representation promises a world determined by human need rather than private profit, insofar as the painting accordingly ‘engages us on the ground of our bodily mortality, which the reigning universals eclipse as a condition for meaning’. However, we can make similar claims about the praxis of explicitly political artists often cited as precursors to Forensic Architecture. Take Allan Sekula, for instance, who described his work as ‘realism not of appearances or social facts but of everyday experience in and against the grip of advanced capitalism’. This is clear even in the title of a photographic diptych by Sekula from 2002-03, Volunteer Watching, Volunteer Smiling, in which an individual attempting to deal with a disastrous oil spill off the coast of Spain and Portugal does precisely what the title says.

Instead, I would suggest that in the context of the gallery space, Forensic Architecture’s work invites dynamics of spectatorship akin to those elicited by the work of blockbuster blue-chip conceptual art celebs such as Ai Weiwei or Doris Salcedo, which we might say is the predominant mode of ‘political’ art today. To draw from personal experience, I invigilated a 2012 Salcedo exhibition at White Cube featuring Plegaria Muda, 2008-10, an installation which filled the space with sculptures consisting of two tables the average size of a coffin stacked on top of one another, supposedly representing the massacre of impoverished youths in Colombia who were lured into joining the army, and then murdered and dressed as defeated guerrillas. Standing there, I often heard salespeople recount this description to the gallery’s clients in an effort to convince them to buy one of the sculptures. The Forensic Architecture work similarly operates on the level of intellection, denouncing specific injustices, rather than indicting the rationality which leads to such injustice in the way that art is capable of doing.

In 1947, at the inception of the Cold War, Harold Rosenberg and Robert Motherwell wrote in a joint statement that ‘the deadly political situation’ exerted such ‘an enormous pressure’ that it was tempting to conclude that one should give up art and dedicate oneself to ‘manipulating the known elements of the so-called objective state of affairs’. Surely similar thinking today motivates the sense that we shouldn’t concern ourselves with whether Forensic Architecture’s work is art. Yet Rosenberg and Motherwell went on to assert that artists who nevertheless continued to make art had ‘the extremest faith in sheer possibility’. I take this to mean that art was justified in its immediate uselessness because in it we find the possibility of another mode of cognition. And I hope the same is true today.

The fight against dominant powers is absolutely crucial, not only in the legal sphere as with the work of Forensic Architecture, but also in workplaces and the streets. Art, however, might still give us a glimpse of what it is that we’re fighting for.

Daniel Neofetou recently completed a PhD at Goldsmiths University, London.

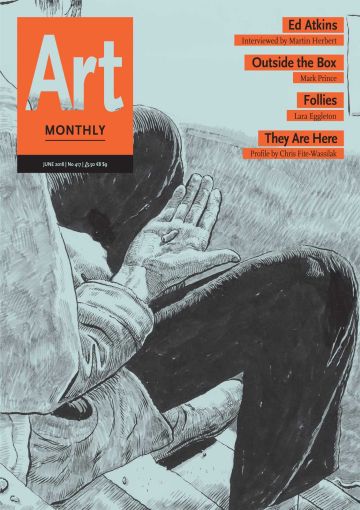

First published in Art Monthly 417: June 2018.