Profile

Carolyn Lazard

Giulia Smith discusses the Philadelphia-based artist’s political agenda, which centres on changing the institutional treatment of disability rather than merely representing it

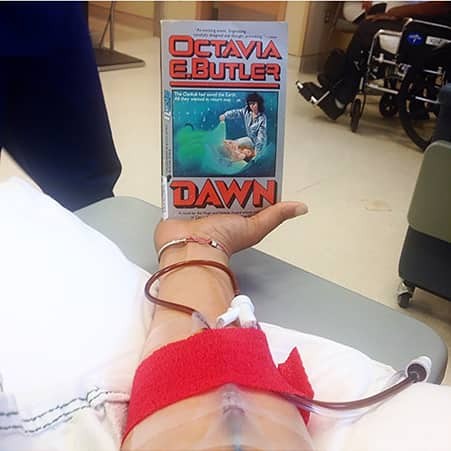

Carolyn Lazard, In Sickness and Study, 2015–

For the past six years, Carolyn Lazard has been reconfiguring the place that chronic illness occupies inside the museum. Traditionally, the art world understands illness through a romantic lens, with the struggling mind-body often seen as the ideal host for the tortured spirit of the genius. Lazard seeks to replace this tired mystique with a more politicised approach. ‘Feminism teaches us that the personal is political, but in order to politicise sickness one has to depersonalise it first,’ the artist maintains. In keeping with this premise, their artworks (the artist prefers a plural pronoun) are carefully drained of excess subjectivity. Irrespective of medium, Lazard privileges a structural vocabulary that is light on emotive representational content. This choice is dictated by the artist’s political agenda, which centres on changing the institutional treatment of disability rather than stopping at its representation.

For Extended Stay, 2019, a piece made for the current Whitney Biennial (Reviews AM428), Lazard repurposed a television monitor of the kind used in chemotherapy infusion rooms. What is distinctive about this technology is that it is designed for a single user. The screen is attached to a prosthetic arm that encircles the seated body of the patient, allowing them to watch their programme of choice. At the Whitney, the same device put a largely able-bodied audience in the position of someone who would most likely find the Biennial exhausting. While the bench installed in front of the monitor provided a place to sit and rest, the piece as a whole highlighted the physical and ethical limitations of the museum as an institution that aspires to be socially accessible and diverse. In 2018 Lazard addressed this issue head-on in a brilliant lecture titled ‘Crip Time’ (available on YouTube), denouncing museums for ‘wanting disabled art and disabled discourse on non-disabled time and in non-disabled space’.

In contrast with those who advertise the therapeutic benefits of putting art inside hospitals, Lazard insists that ‘the hospital must to be brought to the museum’. I take this to mean two things. First, that people living with chronic illness should be made to feel genuinely welcome inside museums through greater access to space, capital and power, as well as through the imple- mentation of more thoughtful labour conditions. Second, that museums should be more critically engaged with medicine and its practices. For Lazard, this means taking the consultation room into the public arena. Because illness makes us desperately vulnerable and totally dependent on a cure, it is incredibly difficult to resist the protocols of the medical-pharmacological sector. Much of Lazard’s work explores how consent fails to be fairly negotiated in the treatment process. Extended Stay, for example, was programmed so that the monitor would zap frantically between different cable networks – a small tweak, but enough to turn what was supposed to be a comforting distraction into a source of torment. A similar logic governed A Conspiracy, an installation created in 2017 for Essex Street Gallery in New York. The piece featured a network of Dhom white noise machines interspaced at short intervals across the ceiling. Since the 1970s, these devices have been used in US hospitals to soothe patients, but in Lazard’s hands their humming vibration acquired an oppressive quality. Through sheer repetition, the therapeutic was repurposed as the subtly persecutory, leaving the audience to draw their own conclusions about the disciplinary side of the care industry.

Consensual Healing, 2018, explores similar issues but with a greater emphasis on trauma. Visually, the piece nods to the simple animations of EMDR videos used to treat subjects with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. All we see is a small yellow ball swinging back and forth across the screen. In contrast with this simple scene, the dialogue features a client talking to their therapist about a repressed memory of harvesting someone else’s eggs before undergoing an ‘extraction’ procedure. The exchange is based on Bloodchild by Octavia Butler, a short story commonly associated with the trauma of slavery even though the author intended it as an abstract commentary on romantic relationships. In Lazard’s reinterpretation, the key elements of Butler’s fiction – the misery of co-dependency, the fact of biopolitical exploitation, the inevitability of surgical violation – become unmistakably linked to the experience of undergoing medical treatment.

In 2013 Lazard began suffering from the symptoms of Crohn’s Disease and a range of additional autoimmune disorders, and, while knowledge of their biography is not essential for understanding their work, it is important to recognise that this artist forged their politics in the crucible of a life-changing health crisis. Previously, they had specialised in film, working on ambitious and physically challenging shoots, but following their first flare-up they had to drastically reconceive their practice. For Support System (for Park, Tina and Bob), 2016, Lazard spent an entire day in bed as individual members of the audience were invited to pay them a visit at the price of a bouquet of flowers. The piece was partly a homage to Bob Flanagan, who organised a similar performance while suffering in the throes of cystic fibrosis (Visiting Hours, 1992). It was also a salute to Park McArthur and Constantina Zavitsanos, two contemporary artists who, like Lazard, live with disabilities. Together, this cohort is redefining what ‘support’ means in an art context.

It is difficult for those who are not presently affected by chronic illness to appreciate just how isolating it can be. Creating collective networks is a fundamental part of what Lazard does as a politicised artist who is also a politicised patient. In 2013 they co-funded Canaries, a support group and art collective for people with autoimmune disorders and other chronic conditions. Their artworks are no less convivial. Support System was explicitly conceived as a meeting ground, without the institutional affectations of much socially engaged art. Similarly, In Sickness and in Study, 2015–, addresses an online community of likeminded ‘students’. The series consists of 14 Instagram posts, each portraying the cover of a book read by the artist whilst undergoing intravenous iron infusions. With titles ranging from Alison Kafer’s Feminist, Queer, Crip to Butler’s Dawn, Lazard’s syllabus nods to a readership with compatibly critical attitudes towards heteronormative conceptions of what it means to be healthy and ‘on track’.

Writing is another way of reaching out to other people. In the year of their first flare-up, Lazard published ‘How to Be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity’, an online article that casts a stark light on the failings of Western biomedicine. The essay went on to influence artist Johanna Hedva (author of ‘Sick Woman Theory’, 2016 – see my feature ‘Health v Wealth’ AM428), who with Lazard is pioneering a hybrid literary genre at the intersection of survivor account, artist manifesto and philosophical text. Also written in this vein is ‘The World Is Unknown’, 2019, a highly engaging meditation on the role that belief plays in shaping our relationship with sickness and healing. Both essays are available on Lazard’s website. I highly recommend reading them, and not just because they are beautifully written – what is most compelling about these texts is their inquisitiveness. Lazard is not your typical artist who regurgitates Michel Foucault in dried-up chunks. Their experience of living with a complex array of symptoms, some of which elude the medical establishment, makes them uniquely attuned to conflicting worldviews. Their authorial voice – concrete, politically integral, intellectually open and even hopeful – is immensely refreshing and commands great respect.

I have intentionally relegated this side of Lazard’s practice to the end of this article because the artist is adamant that their publications should be kept somewhat separate from their art. Writing is where the first person is allowed to creep in, if only to create a critical framework for Lazard’s practice as a whole. It seems a pity that in the UK this hugely promising artist should be known primarily through their writings and to a lesser extent their videos. Fortunately, this is now changing. This past summer A Conspiracy was shown at Cell Project Space alongside works by Adrian Piper and Donald Rodney, two artists who Lazard counts as inspirations (Reviews AM428). The same gallery is now planning a solo show for Lazard, which is due to open next April. It will be a welcome opportunity to engage with the full breadth of their practice and really take stock of its implications, which are profound.

Giulia Smith is an art historian based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 429: September 2019.