Review

Crip Time

Martin Herbert is challenged by MMK Frankfurt’s ambitious exhibition of disability-related art

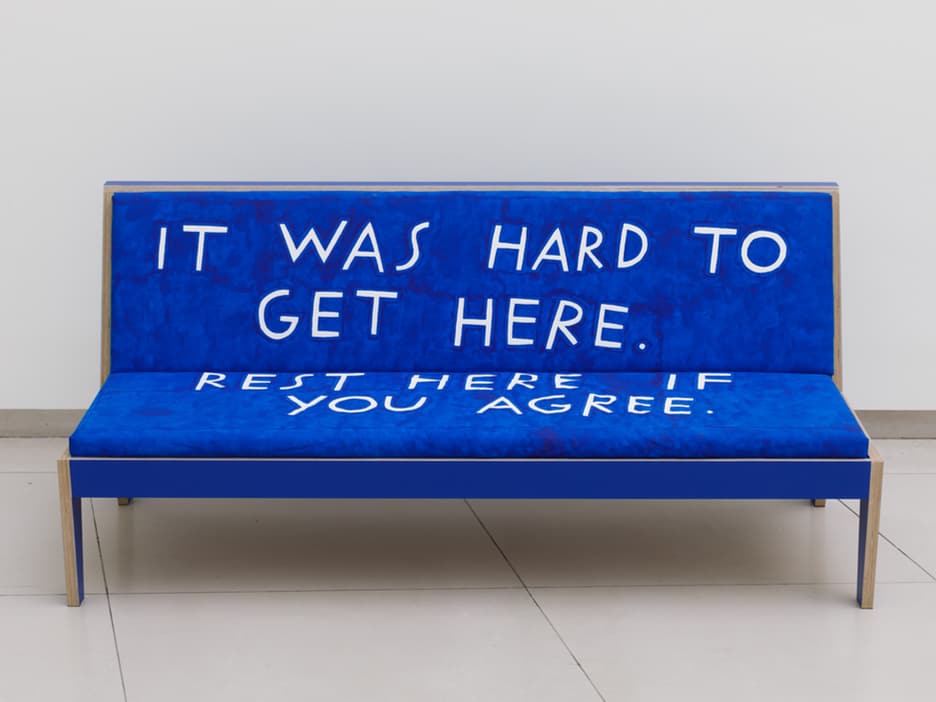

Shannon Finnegan, Do you want us here or not, 2018/21

The title of this 41-artist show is a layered one. For an exhibition focused primarily on artists who have or had a disability, it might immediately suggest a belated moment of collective spotlighting. Yet ‘crip time’ is also a phrase strongly associated with disability-studies academic Alison Kafer, who uses it to refer to a reimagining of how long a given activity might take, one not based on ableist notions, and the value of such time. And, thirdly, for a show whose info booklet opens with a quote from artist/musician Johanna Hedva – ‘You don’t need to be fixed, my queens – it’s the world that needs the fixing’ – it expands to address a social reality that, driven by capitalist obsession with productivity, has little patience for vulnerable and damaged bodies, and in which the able-bodied and disabled are all enmeshed. As such, at a moment when ‘care’ is a buzzword in contemporary art, ‘Crip Time’ is a timely proposition. That there are several big-name artists here who are not disabled initially serves to confuse; later, though, it makes a degree of sense.

High on the walls of the atrium-like opening gallery, Christine Sun Kim has repeatedly painted her own notation for ‘echo’ in US sign language, a curving V that represents fingers touching a palm and then retreating from it: Echo Trap, 2021. Using a subjective visual analogue for what is already a translation method, she asks the viewer to countenance a lived reality inseparable from the layers of approximation in which what one wants to say is filtered through sign language and interpreters. That the show might thus be grounded in empathic processes and mutuality is reaffirmed by the presence, on the floor, of Emily Louise Gossiaux’s Dancing With London, 2021, two papier-mâché sculptures of her guide dog standing on hind legs as if a human inviting us to dance, and to enter, to a degree, the artist’s reality. Nearby, meanwhile, there is the first of several benches provided by Shannon Finnegan and inscribed with texts such as, ‘I’d like more time with this artwork but all this standing is painful. Sit if you agree’ – an intervention both thoughtful and barbed. Able-bodied viewers visiting MMK’s large, multistorey space are liable to leave with aching legs; until this point, though, they might not have considered that they have it easy.

From here, ‘Crip Time’ engages with a gamut of subjectivities, sometimes interlinked. Being seen, or otherwise, is a thread: a roomful of Derrick Alexis Coard’s drawings, from the 2010s, of self-assured-looking black men with beards addresses both masculinity and the history of Coard’s own experiences with mental illness; the drawings, made by a bearded black man and accompanied by marginal texts concerning healing, are acts of representation that also apparently boosted his self-esteem. Leroy F Moore Jr’s Black Disabled Art History 101, 2015, by contrast, is a video taxonomy of disabled black musicians whose histories have been occluded despite their great cultural achievements. In Michelle Miles’s short video hand model, 2018, we hear that the artist’s nascent modelling career was cut short when it was discovered that she used a wheelchair. Franco Bellucci’s wall-mounted sculptural reliefs – lashed-together assemblies of used toys, rope, rubber, wheelchair wheels and more – feel sourly inseparable from the Italian artist’s biography: following a brain injury in childhood, he was confined to a psychiatric ward for a decade and tied to his bed. Guadalupe Maravilla’s hugely resonant Disease Thrower #15, 2021, surrounds a gnarly, organic central sculpture, a ritual instrument for healing – a mix of what look like fossilised ferns, shells, plastic figurines and a serpent – with gongs whose vibrations are also meant to promote recovery.

Maravilla is a colon cancer survivor, and ‘the components of [his] sculptures are intimately linked to his biography’, the info booklet notes. That kind of intertwining is fundamental to ‘Crip Time’ – whose artists elsewhere engage with HIV/AIDS, sickle-cell anaemia, rogue medical testing, racism underlying asymmetric vaccinating, gouging healthcare costs and more – and makes the show a sustained challenge. A lot of the works require reading to unlock, and in so doing uncover the artist’s pain; evaluating the work then requires separating out fundamental sympathy for suffering from any qualitative reading of the art, if that is possible. Meanwhile, and relatedly, inclusions which seem to view disability and sickness from outside can feel off-key. It’s not wholly clear what Judith Hopf ’s trademark ‘sheep’ – made from pouring concrete into cardboard boxes, then giving the blocks scrawled faces – are doing here. The booklet suggests that sheep are ‘dependent on the care of their flock’, but it feels more like an attempt to shoehorn a well-known artist into the mix, as is the case with Cady Noland’s Stockade, 1987/88, seemingly included because it includes steel walkers; Gerhard Richter’s Tante Marianne, 1965/2018, a photographic reproduction of his painting of his aunt, who underwent forcible sterilisation under the Nazi regime before being murdered in a psychiatric hospital; and various works by Isa Genzken that appear unrelated to her bipolar disorder. Going down this ‘show-your-wounds’ interpretative route, though, leads one into an uncomfortable zone of judgement, where it’s not clear if the viewer is establishing an involuntary hierarchy of infirmity or if the show, in always pointing to real pain, has sought to immunise itself against criticism.

The logical justification for including disability-adjacent artists in ‘Crip Time’ is to suggest, in bridging fashion, that we are all in the orbit of sickness and disability, either because it could easily befall any of us, because we know people to whom it has, or because we all have a duty of care and understanding, which this show’s repeated staging of occasions for empathy promotes. MMK is a large institution and this show, which fills it, might quietly exhaust a viewer with its omnidirectional evocations of the suffering of others, in a way that one might not realise until one exits and exhales. That minor discomfort, which is nothing compared with what many of these artists have gone through, is in turn a measure of one’s own capacity for empathy, which can almost always be stronger. As such, despite and even because of its problematic aspects, ‘Crip Time’ insists that you think with it not only while you are in front of the art, but also as you move through the world after you leave.

Martin Herbert is a writer based in Berlin.

First published in Art Monthly 452: Dec-Jan 21-22.