Artlaw Retrospective

About Artlaw

Henry Lydiate on the development of Artlaw over the past half century

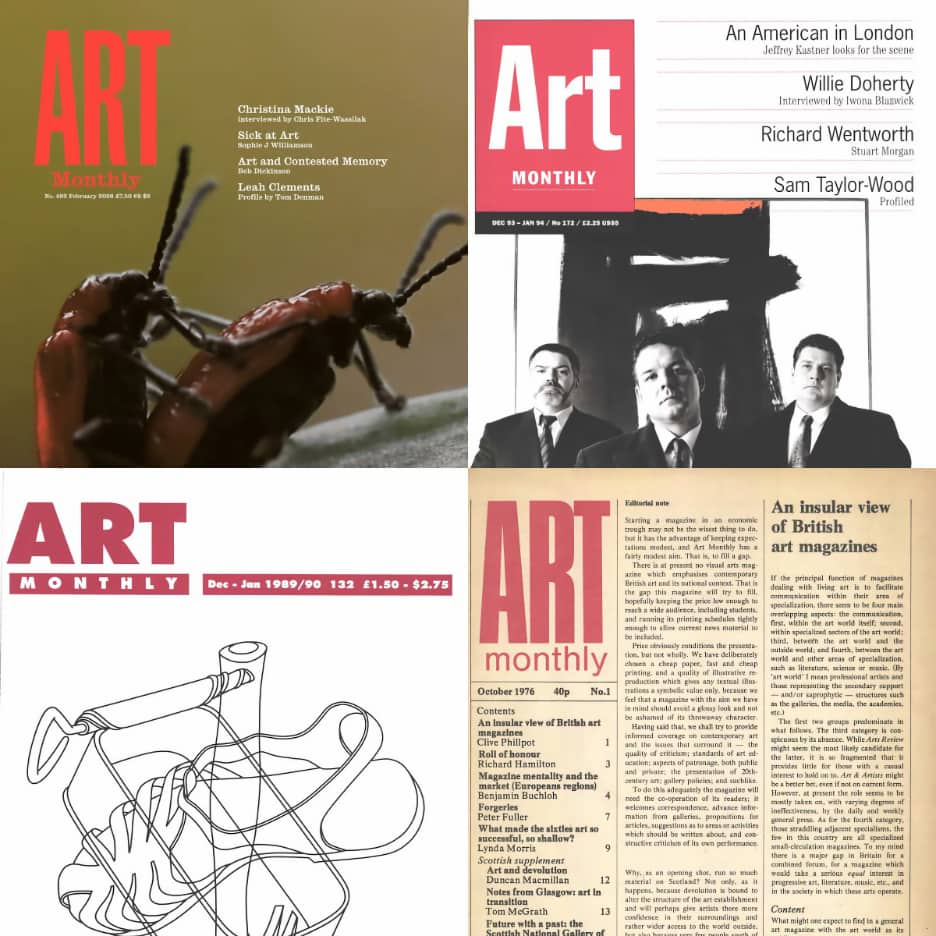

Art Monthly cover designs 1976–2026

In April 1971, the front cover of Studio International, the bi-monthly illustrated contemporary art journal, reproduced the first of a three-page radical new legal tool for artists: The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement (see Interview with Seth Siegelaub in AM326 and 328). Sponsored by the School of Visual Arts in New York City, the Agreement was published a month earlier as a poster, with a manifesto statement of its primary objective: ‘to remedy some generally acknowledged inequities in the art world, particularly artists’ lack of control over the use of their work and participation in its economics after they no longer own it’.

Two New York City-based professionals jointly authored the Agreement: Seth Siegelaub, an innovative Conceptual Art curator-publisher and former dealer, and Robert Projansky, a recently qualified attorney. Siegelaub had identified inequities via ‘extensive discussions and correspondence with over 500 artists, dealers, lawyers, collectors, museum people, critics and other concerned people involved in the day-to-day workings of the international art world’.

Projansky drafted an innovative legal framework of equitable remedies, designed to be used as the standard agreement between artists and collectors whenever works were sold or changed hands, regardless of the artist’s stature or type of work. Terms and conditions specified the respective rights and responsibilities of the collector/purchaser and the original creator, controversially including: the right for artists to refuse exhibitions of their work, the right to know who purchased it and, most contentiously, the right to claim 15% of any resale profits (because the US did not then, and does not currently, have a federal artist’s resale royalty right statute).

The Agreement was designed to create transparency in an industry that was then – and is often today – widely criticised for its characteristically opaque, private, cash-based, and legally informal art business customs and practices. Its use was advocated by artists’ collectives calling for the regularisation and decentralisation of the contemporary art market and its institutions. It was revised and varied by others several times, but few collectors ever signed the original or its variations. Yet, over the next 50 years, it had a major influence in stimulating global discourse over ways to improve legal and business practices relating to contemporary visual art – and even came to be specifically associated with Conceptual Art and Minimalism. Showcasing it in Studio, one of the most influential fine art periodicals in the English-speaking world, shot a broadside across the bows of the contemporary art world throughout the 1970s and beyond.

Peter Townsend was Studio International’s editor responsible for the Agreement’s publication. After serving seven successful years, in 1975 Townsend stepped down to become the first editor of Art Monthly, which he co-founded with former gallery owner Jack Wendler. Decidedly unlike Studio’s high-quality, full-colour journal, only Art Monthly’s front cover masthead was red: its contents were printed in black and white on a newspaper-style thin paper format, which Townsend said was intended to be a low-cost ‘throw-away’ roughly printed bulletin – rather like Private Eye.

New material was commissioned for Art Monthly’s inaugural issue, published October 1976, including original artwork by Richard Hamilton: an acrostic tribute to Marcel Broodthaers, who had died earlier that year. As a recently qualified barrister and aspirant art lawyer, this writer was asked to contribute an article dealing with current legal issues relating to visual art – under the one-word title, ‘Artlaw’. The first article drew on recent interviews with artists, on both sides of the Atlantic, who had substantiated the inequities addressed five years earlier by Siegelaub and Projansky. Artlaw was given only one editorial direction over the next five decades: ‘keep it au courant’.

A further initial focus was on matters that had been revealed by Lord Redcliffe-Maud’s landmark enquiry into the infrastructure of arts funding in Britain, the results of which had recently been published: Support for the Arts in England and Wales. Parts of this report chimed with Artlaw’s raison d’être, and the following observations were particularly striking:

‘Few of the art courses make any serious attempt to prepare students for life as an artist. Some of the most serious problems facing artists when they emerge from training are these: how to find and pay for studio space and meet the cost of materials and equipment; how to publicise their work and interest galleries in it; understanding how commercial galleries operate and what arrangement should be sought between artist and gallery; how to find part-time teaching work; the position of the self-employed person for Income Tax and National Insurance purposes. Few artists are taught at college about the patronage structure on which many of them will rely for help, or about rights to public assistance.’

Further research into these matters was conducted. Art schools were visited throughout the UK to explore with students and tutors ‘life after art school’. These sessions developed into what art schools now call ‘professional practice’ studies. This essential knowledge transfer continues to be embedded in the column.

In these early years, geographical focus was on the contemporary art world in the UK and Ireland, with occasional forays overseas. In the US, links were established with a small network of nascent ‘lawyers for the arts’ in Chicago, Minneapolis, New York City and San Francisco; contacts are maintained today with now established arts lawyers practising throughout the country. Australia’s Council for the Arts commissioned Artlaw to conduct empirical research there: to establish whether there was an unmet need for the provision of specialist legal services to artists throughout the country, and to make recommendations accordingly. This work led to the formation of the Arts Law Centre of Australia in 1983, whose inaugural and current mission is ‘to empower artists by offering free or low-cost legal help, education, and resources’.

In France, Pablo Picasso’s son Claude had recently become manager of his late father’s Estate and he sought Artlaw’s help to enforce the artist’s copyright in the UK, where there were substantial unauthorised reproductions – there was no UK organisation enforcing violations of artists’ copyrights. This collaboration, including the Picasso Estate’s seed-funding, was instrumental in the establishment in 1984 of a UK organisation solely dedicated to enforcement of artists’ copyrights, the Design and Artists Copyright Society (DACS), whose first members notably included: Peter Blake, Patrick Caulfield, Richard Hamilton, Susan Hiller, Alexis Hunter, Eduardo Paolozzi, the Picasso Estate, David Shepherd and Joe Tilson. Today, DACS has over 180,000 artist members worldwide, and has distributed over £250m in royalties to artists and their estates since 1984.

In August 1989, UK copyright law was radically improved when the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA) was implemented. Arcane provisions of the previous Copyright Acts of 1911 and 1956 were repealed and replaced by a more logical and consistent new framework. Artlaw covered key changes during the following year, but the reforms were substantial and required more in-depth treatment. Accordingly, Art Monthly published a separate Artlaw publication in 1991: Visual Arts and Crafts Guide to the New Laws of Copyright and Moral Rights.

In November 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, symbolising the end of the Cold War, paving the way for German reunification in 1990, and leading to the collapse of communist regimes in the USSR and its satellite states in Central and Eastern Europe by 1991. The European Economic Community (EEC) was reconstituted as the European Union (EU) in 1993, which had included the UK and Ireland since 1973. In 2004, EU membership expanded to admit Poland, Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Cyprus and Malta; then Romania and Bulgaria in 2007. By integrating former communist states and fostering stability, growth and shared European identity, the EU’s political and economic landscape was significantly reshaped. In particular, the EU regularly coordinated and harmonised new laws directly applicable to all its member countries, coverage of which required Artlaw permanently to broaden its focus.

For example, the EU directed all member countries to harmonise their differing copyright terms by 1995, setting its standard duration as the author’s life plus 70 years. The UK complied with this requirement by amending its CDPA: from 1996 copyright would increase from 50 to 70 years after the author’s life. Each EU country needed to make transitional provisions dealing with the length of copyright of works made before the harmonisation. The UK’s transitional duration rules were complex, which Artlaw explored and explained: essentially, the length of copyright would vary depending on whether a work was made before 1957; or made between 1957 and 1989, and had been published.

In 2001, another EU harmonisation direction required all member countries to implement a standard scheme of artist’s resale right by 2006. The UK enacted its Artist’s Resale Right Regulations accordingly. From 1976, Artlaw continually advocated the introduction of this right in the UK, and from 1984 supported the campaign by DACS arguing for its enactment, then its continuation after Brexit.

In 2016, when the UK’s referendum votes were in favour of exiting the EU, Artlaw covered the likely effects of Brexit on the contemporary art ecosystem in the UK. Consideration was given to the abolition of free movement, to and from the EU, of artworks and artists and other professional practitioners. Particular concerns were expressed on how to deal with the existence – perhaps removal – of EU rules and regulations that had been integrated into UK law over the previous decades. In 2018, to maintain legal certainty, the UK enacted the EU Withdrawal Act, which converted all EU law into UK domestic law on exit day, 1 January 2021. In this way, ‘Retained EU Law’ continues to be a fundamental part of UK law – including artist’s resale right – but from which UK legislation may now diverge.

Blockchain was a pivotal technological advancement of the early 21st century, having far-reaching effects on economics and society. An obvious use of blockchain technology was for the documentation of unassailable records of art ownership, which raised key questions as to whether there were wider and more profound applications of blockchain technology in the art world. Artlaw interrogated these matters, which also became the subject of year-long research jointly conducted by Oxford University’s Internet Institute and The Alan Turing Institute (the UK’s body for data science and artificial intelligence research). Funded by DACS, the resulting research report was launched at an event held in the House of Commons in May 2018: Blockchain and Financialisaton in Visual Arts.

By 2021, the art world had adjusted to the impact of the global Covid-19 pandemic’s lockdowns, using digital technology to move towards exclusively online activity. In the art market, it was said that the old-world order was being demolished. Art fairs were postponed or cancelled, auctions sold only online, galleries communicated with clients via email and Zoom. One event ‘shook the market to its core’: Christie’s online auction of Beeple’s born-digital NFT, Everydays: the First 5000 Days, which fetched $69.3m with fees, payment for which was accepted in cryptocurrency. Artlaw reported this landmark event, the proliferation of art NFT works it stimulated over the following two years, and their sales using smart contracts secured with blockchain technology. Emerging legal implications were, and continue to be, explored, including: copyright infringement; stealing then minting and selling digital copies; questionable terms and conditions of sale from online trading platforms; the potential imposition of taxes on those involved in art NFT trading transactions; and money laundering regulations, especially when paying with cryptocurrency.

In January 2023, an unprecedented lawsuit was filed in a US Federal Court. It is a ‘class-action’ comprising separate claims by three artists, who bound themselves into a single lawsuit based on the same legal issue (or classification). The lawsuit is against three companies, each of which allegedly used the claimants’ artworks to train an AI (Artificial Intelligence) visual art tool to power ‘text-based image creation’ – thereby violating each artist’s copyright. Artlaw reported this case, now set for trial in 2027, and explored commercial use of AI in the contemporary art ecosystem. The recent rapid growth and popular use of AI visual art tools have already prompted further significant legal controversies, with many more likely to emerge.

In March 2023, the US Copyright Office published instructive guidance on Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence. The guidance clarified that work containing wholly AI-generated material may not be copyright-protected, if it was not the product of ‘human authorship’; but, where a human selects or arranges or modifies AI-generated material in a sufficiently creative way that ‘the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship’, then copyright protection may apply. The US is a world-leader in the development of both AI technology and intellectual property law, and Artlaw considered whether this latest AI copyright guidance was likely to influence the thinking of most other jurisdictions. Artistic works wholly generated by AI tools are likely to proliferate into the future, and continue to pose problems for the world’s copyright law nations – most of which have to date largely rejected, or not yet considered, such works being copyright-protected.

Artlaw’s geographical scope has become increasingly global since the 1990s, when the mainstreaming of the World Wide Web triggered the Internet Revolution. Communication costs reduced, trade liberalised, and manufacturing operations shifted to strongly developing economies such as Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia and Turkey. Global economic growth stimulated the strong development of markets for culture worldwide, especially for access to and consumption of contemporary visual art.

The global art market has experienced significant volatility and growth since 1990, driven by economic cycles, the rise of new collectors, and digitisation. After a major collapse in the early 1990s, the art market reached a peak of $68bn in 2014, $67bn in 2023 and declined to $57bn in 2024 due to a cooling high-end market. The US and UK and China are the art market leaders, together representing 76% of the total sales in 2024. The US is the decades-long global leader with 43%, centred on New York City. The UK’s turnover was 18%, with London its centre. China achieved 15%, Hong Kong being the primary hub for Asia’s high-value sales. Art lawyers are likely to develop their specialism in countries where there is a vibrant economy that supports art market trading activity and related cultural enterprise. Artists have tended to do likewise throughout art’s history.

Five decades ago, the visual arts ecosystem was not the interrelated and interdependent global network it is today. It was a loose network of national cultural organisations and marketplaces that connected with others from time to time. Since the mid 1970s, the handful of publications on art law have tended to focus on national – not international – laws and offer few insights into the operations of the global art world. The late John Henry Merryman, a US-based legal scholar, is now remembered as one of the most influential academics in the field of artists’ rights and cultural property.

In 1971, Merryman was appointed professor of law at California’s Stanford Law School, and began delivering a lecture series on art and the law, which he developed to form the basis of the first edition of Law, Ethics and the Visual Arts (LEVA), which was published in 1979 and quickly became a foundational text in the field, at a time when this niche cultural legal practice was in its infancy. Four more editions were published until 2007, each one becoming less US law-oriented and increasingly international in scope as the art ecosystem became global.

Merryman died in 2015, and LEVA’s long-awaited sixth edition was published by Cambridge University Press in 2025. It was co-authored by Stephen K Urice, professor at the University of Miami School of Law, and Simon J Frankel, a judge on the Superior Court of California in San Francisco, who also teaches Art and the Law at Stanford Law School.

Merryman’s initial and enduring interest in law and ethics in the visual arts was doubtless stimulated by his 60-year marriage to an art dealer. Other pioneers were similarly attracted into this ‘wild frontier’ through personal association with individuals and entities involved in the art world, who sought advice and assistance to address their legal and ethical concerns.

Artlaw had its origins at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, where this writer graduated with a law degree in 1969; and was drawn into friendships with students in the University’s Fine Art Department, who had been tutored by Richard Hamilton, to whom an introduction was made. Through these liaisons, experiences of both art and the law were shared. As a result, it became clear that the law relating to the visual arts was not only complex and esoteric, but also that few UK lawyers had a good working knowledge of the art world.

In 1975, by then a recently qualified barrister, a successful application was made to the Greater London Arts Association (GLAA) to endorse and support a research project: to investigate whether artists in London had unmet needs for legal services; and, if so, how those needs could be met. GLAA granted modest funding and provided a small research office. The chair of GLAA was Peter Townsend, who commissioned this Artlaw column for the first issue of Art Monthly.

Henry Lydiate is an art lawyer and adviser to www.artquest.org.uk.

First published February 2026.

Art Monthly celebrates its 50th anniversary and 500th issue in October 2026. Henry Lydiate marks the magazine’s 50th year by reviewing his Artlaw column since its first publication in 1976. Throughout 2026, one broad subject is explored each month, noting significant events and issues, and commenting on key changes and developments to date.