Report

Letter from Naples

Mark Sladen encounters a chilling new film in a city where edgy art has long been welcome

Diego Marcon, The Parents’ Room, 2021

In September I travelled to Naples to see a film installation by the Italian artist Diego Marcon. The work in question is The Parents’ Room, 2021, a 35mm, six-minute film which can either be shown as a cinematic screening or, as I saw it, a looped installation. The action is set in a single room, where a man sits on the side of a double bed, snowflakes drifting in through the open window. A blackbird alights on the windowsill and starts to trill, its song developing into an orchestrated melody. The man begins to sing, telling us of his homicidal crimes, while in the next shot we are introduced to his son, who takes up the song while lying at the foot of the bed. Subsequent shots introduce a daughter, standing by the window, and a wife, lying in the bed. The father and his family reveal that he has killed all of them and subsequently himself.

Various elements of this surprising film suggest the world of musical cinema. One is the visual stylisation of the room, which is bathed in light, its carpet almost white. Another is the lush score, by composer Federico Chiari (a long-time collaborator of Marcon’s). Moreover, there are elements of CGI – the falling snow and the singing bird – that invoke the world of Disney. The strangest elements of stylisation, however, are the prosthetics worn by the performers. These were cast from the actors’ own hands and faces to give the cast the appearance of puppets, their eyes and mouths peeping through from underneath the silicone. Much of the stylisation of the film seems to channel the emotionality of classic Hollywood, but the prosthetics have the opposite effect, stripping the actors of expression. The way the film handles its violent subject matter also favours the limitation of affect: no bodily trauma is shown; and the libretto, rather than indulging in gruesome descriptions of the crimes, is studiedly banal.

Marcon is an artist in his 30s, best known for his film projects, whose work has been gaining attention in recent years, including on the film festival circuit (the piece in Naples was in fact premiered at Cannes earlier in the year). There are obvious connections between The Parents’ Room and former pieces by the artist. In particular, violence and danger have been consistent themes in his work – which has often included the trope of the imperilled child. Marcon’s most celebrated work to date is Monelle, 2017, a 35mm film which plays with the grammar of the horror movie, and consists of shots of girls sleeping – moments of illumination on an otherwise dark screen – threatened by fearsome CGI protagonists. Ludwig, 2018, meanwhile, is an animated short set in the world of cartoon jeopardy, and which centres on a boy singing, in the lieder style, within what appears to be the hold of a ship on a stormy sea. In both of these works, as in The Parents’ Room, the intimation of peril is undercut by a highly self-referential approach to the language of film.

Marcon’s piece was produced by INCURVA, a cultural association based in the Sicilian town of Trapani. INCURVA managed to procure a major grant for the project from the Italian Council, an award that included funds to fly in journalists, which can’t be common practice for cash-poor Italian institutions. However, Marcon won the MAXXI Bulgari Prize in 2018, which is a big deal in the Italian art world, and this must have been attractive to sponsors. The film is being shown this autumn in the Madre museum in Naples, where I saw it, in Trapani and at the new Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. In addition, the exhibition I saw was curated by Eva Fabbris and Andrea Viliani, who are both power players in the Italian contemporary art world: Fabbris is a curator at Fondazione Prada in Milan, while Viliani, who was the director of the Madre until 2019, now leads research at Castello di Rivoli, outside Turin.

All of this led me to conclude that Marcon is hot stuff, but how his work fitted into Naples was less clear. It might have been more evident if Viliani was still running the programme at the Madre, since that of his successor, Kathryn Weir, appears to have a very different tone – at least if the post-pandemic reopening show was anything to go by. This exhibition, ‘Utopia Dystopia’, which occupied the whole of the floor below the Marcon installation, was a biennale-style meditation on local politics, history and material culture, a rather worthy exercise with little of the perversity exhibited in Marcon’s film. Having said that, the Madre is clearly an institution that has struggled to find its feet, and which has lurched between different models of operation. On the first floor of the building is a sequence of bombastic permanent installations by art stars of the 1980s and 1990s – including Francesco Clemente, Jeff Koons and Anish Kapoor – works that were commissioned for the museum’s opening in 2005, and which speak of another institutional vision altogether.

The evidence of my short trip to Naples, however, is that the city has a distinguished contemporary art legacy, albeit one that has been better embodied by artists and private galleries than by public institutions. The 1960s and 1970s were glory days for the Italian contemporary art scene, and the art dealer Giuseppe Morra is one of the people who brought this energy to Naples. The dealer’s legacy is celebrated at Casa Morra, a private foundation that he established in a former palazzo, which is being slowly renovated and which holds an accumulating sequence of exhibitions on aspects of his collection and archive. One particularly fun set of rooms features a group of shamans and charlatans that Morra brought to Naples, including Hermann Nitsch and Joseph Beuys, as well as Julian Beck. The latter was a co-founder of the Living Theatre, who – after they were drummed out of New York in the early 1960s – toured Europe with their countercultural, political, liberated brand of performance art. The ambition that Morra brought to Naples is still detectable at his foundation, which has a hare-brained grandeur: its exhibitions have been mapped out for 100 years.

Marcon’s project, I would say, is also distinguished by its ambition. Having spent 72 hours in Naples – seeing the city’s amazing legacy of Caravaggios and classical sculpture, as well as contemporary work – I came back to view his film again. The Parents’ Room has the unplaceable quality of a really good piece of contemporary art, the sense that the goalposts are being moved, in a way that you may only understand later. I particularly appreciate that male violence both is and is not the subject of the film. The familicidal rage of the white, middle-aged man is at the heart of the piece – invoking the spirit of Jack Torrance, the Jack Nicholson character in The Shining, another film in which peril is heightened by the family’s isolation in a snowbound building. In The Parents’ Room, however, this rage is presented in a way that strips it of much of its spectacular, pornographic, voyeuristic allure. As in many of Marcon’s films, the emotional tone speaks of enervation and entrapment, and the human subject around which the film circles – revealed in all of its characters, including the father – is a helpless, foetal form surrounded by a violence that is social or structural rather than individual, a violence that is symbolised, in part, by the machinery of the cinematic universe.

Mark Sladen is a writer and curator. He recently completed a PhD on Félix González-Torres.

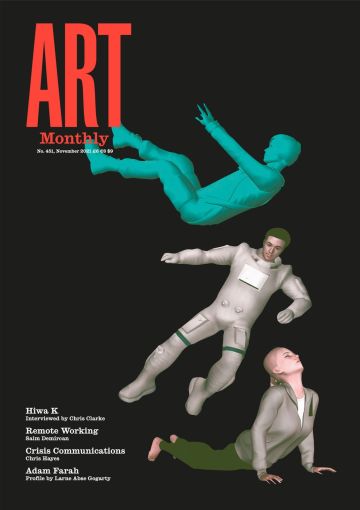

First published in Art Monthly 451: November 2021.