Review

Meiro Koizumi: Battlelands

Amy Luo reviews the Japanese artist’s collaboration with US military veterans

Meiro Koizumi Battlelands 2017

In military parlance, ‘situational awareness’ refers to taking cognisance of one’s surroundings with an aim to identify potential threats. Soldiers are taught to survey any visible bodies – what are hands doing, where are eyes gazing, what garments are figures wearing? The surrounding space is also of concern, to be inventoried for blind spots, entrance points and spaces to take cover. First learned in training, in combat these habits ingrain themselves in the body instinctually. After returning home from duty, many soldiers involuntarily persist in this incessant scanning, a vestigial hypervigilance that is a common symptom of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Scanning is a glaringly recurring action in Meiro Koizumi’s video Battlelands, 2018, which was the focus of this solo exhibition at White Rainbow. ‘Scanning, scanning, scanning ... Not sure what’s happening ... Just don’t want to die,’ recalls one man in the video. He is one of the work’s five participants, all US combat veterans from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Koizumi asked the veterans to wear body cameras and walk through their homes and neighbourhoods, capturing footage of their civilian lives across Miami, San Francisco, San Diego and Oakland. During these perambulations, the participants alternate between describing their immediate surroundings and narrating memories from war. One woman pans the camera across her rigorously tidy kitchen counter and pauses the shot on a white stove. ‘This is where I cook,’ she explains, but suddenly, while the shot lingers in the kitchen, she begins recounting, ‘I can hear the sergeants yelling, “GET OUT OF THE TRUCK, GET OUT OF THE TRUCK!” I can feel the heat. The smoke.’

Such bodycam footage of domestic scenes makes up the entire hour-long work. In the context of military pursuits, the bodycam recalls distressing imagery. Infamously, the White House is believed to have streamed live bodycam footage of the Navy SEAL raid that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden in 2011; that same year, a helmet-mounted camera recorded a British soldier in Afghanistan turning his pistol on a wounded Taliban fighter and firing a fatal shot. Koizumi’s comparably prosaic scenes are clearly meant to undermine these associations. Yet in the work’s suburban terrain of kitchen appliances and palm tree-lined sidewalks, there broods a sustained unease. Partly, it arises from the technical quality of the camera, with its wide-angle lens that forces the rectilinear to curve, and its predisposition to both over- and underexpose, bearing images of a stark, grainy world. This atmospheric anxiety is amplified by a droning soundtrack that accompanies much of the video. Yet this addition feels unnecessary, for what the narrated footage, with its intruding memories, affirms is that trauma possesses the everyday of those who have experienced war, that for them it is the noise of quotidian life – the rumbling of a truck engine, the chattering of crowds – that menaces.

With its profound emphasis on the psychological dimension of partaking in war’s violence, Battlelands finds continuity with Koizumi’s earlier work concerning Japan’s military history. His ‘Double Projection’ video works from 2013 and 2014 similarly explore a war figure, the Second World War Kamikazi pilot, through the to-camera recollection of survivors. However, Battlelands departs from his earlier work not only in engaging non-Japanese civilians – notably a first for the artist – but also in excising the narrators’ faces. The late Harun Farocki (Interview podcast on AM’s website), after trawling through troves of war scenes in mainstream films for his work War Tropes, 2011, had recognised the centrality of the face as trauma’s site of signification: ‘There is no war movie’, he noted, ‘in which the horrors of war did not appear in a moment of epiphany on the faces of the characters: freezing in action, eyes wide open, not wanting to see, but cannot stop looking.’ With its first-person point of view, Battlelands inverts this tradition; in so doing, it shifts emphasis from representation to phenomenology in order to pose the question: how does trauma reorient the body to the world?

Also included in the exhibition in a sombrely lit adjacent room was a sculpture from 2015 titled Sleeping Boy. It comprised numerous copies of diminutive arms, legs and heads, formed of clay and plaster in the likeness of the artist’s young son, which were arranged into a cluster on the ground. Heads lay adjacent to legs and feet, demolishing symbolic hierarchy in emphasis of materiality. Deeply personal, this work reflects a facet of the artist’s practice very different to Battleland’s collaborative and social production. Here, the repeating sculptural forms evoke compulsion and preoccupation, and equally routine and dedication, plumbing the artist’s own paternal anxieties about the fragile mutability of the human body, a counterpoint to the video’s psychological portraits of a generation altered by foreign wars.

Meiro Koizumi’s ‘Battlelands’ is at White Rainbow, London from 22 November to 12 January.

Amy Luo is a writer living in London.

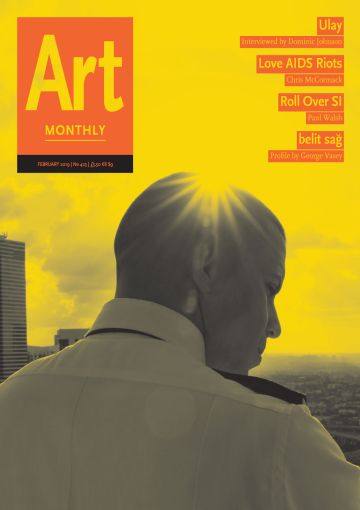

First published in Art Monthly 423: February 2019.