Profile

Shanzhai Lyric

Alexandra Symons Sutcliffe on the way the New York duo’s work charts the flows of capital that shape our world

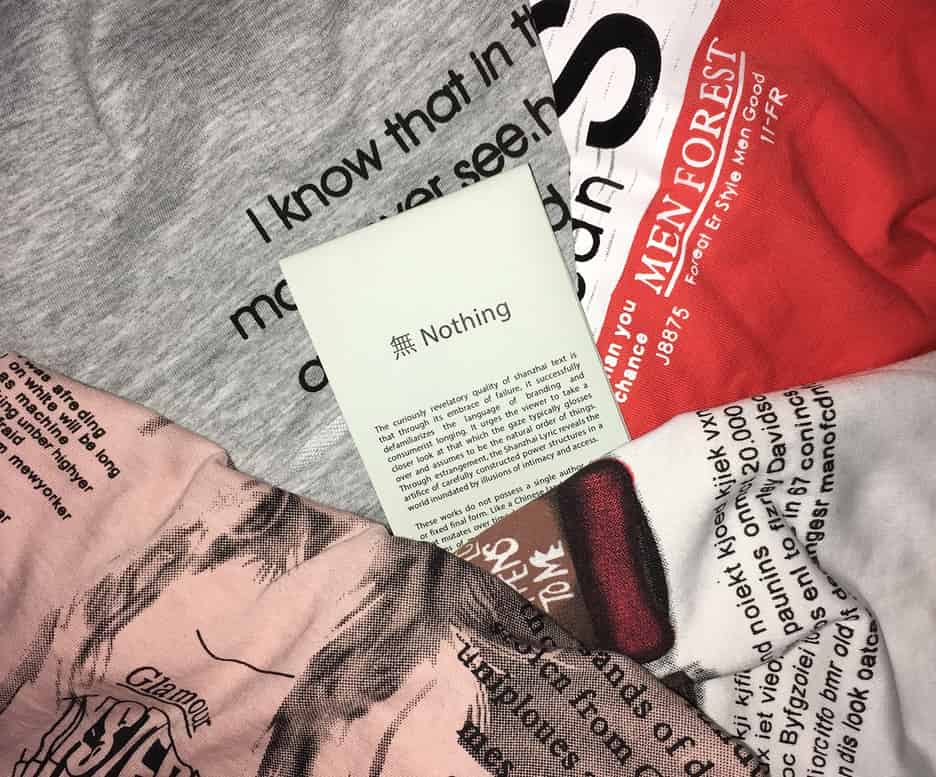

Shanzhai Lyric, Nothing, 2018, mini-publication published by Display Distribute

On our planet made of systems everything seems to flow. The currents of the oceans carry vessels filled with goods and people while mapping and surveillance systems direct and optimise their patterns of travel. This optimal form of travel can encompass both the smooth arrival of valuable cargo and the destruction and expulsion of unwanted people and things. The cultural and technological imposition of international commerce and communication has changed the natural world. Seemingly, there is no longer an outside to the parallactic map of distribution and exchange, nothing untainted to be drawn inside it; we have encircled ourselves with capital and its by-products. Yet, there is still the possibility of divergence. As we continually asset-strip resources, materially or conceptually, it is becoming increasingly necessary to privilege forms of unoriginal creativity. The spoils already having been distributed upwards, the only option left is collective mutation of language, culture and form, since it is in these mutations that other possibilities may emerge.

Initiated in 2015 by Ming Lin and Alexandra Tatarsky, Shanzhai Lyric is an archival project that works with the language of bootlegged consumer goods produced in China, commonly referred to as shanzhai. It is easy to imagine this kind of merchandise: Samsing phones, Adadis trainers, Channel handbags. Sometimes brazenly comic and sometimes subtly simulacral, these approximate products mark themselves in logos remade from the branding of international conglomerates. The fragmentation of the company name simultaneously disassembles the brand’s identity and reaffirms its currency – it is both a dismissive and reifying act. This cut-and-paste technique is also a popular design method for slogan T-shirts, with text seemingly pasted from Word docs, advertising and instruction manuals onto garments: ‘MAY THE BRIDGCS I BURN LIGHT THE WAY’; ‘FREEDON’; ‘OFF IN CHINA’. These are the shanzhai lyrics, a term coined by Lin and Tatarsky to identify the poetry in the language of mass distribution and to describe their own practice of activating shanzhai as counter-hegemonic cultural products. As Lin and Tatarsky explain: ‘Simultaneously naming the phenomenon and naming the project after it has been deliberately confounding. Our intention is to observe and learn from shanzhai as a mode of upending values and put into practice this blurring and confusing of authorship.’

The various iterations of the Shanzhai Lyric project reflect the heterogeneity and multivocal nature of shanzhai. Crossing poetry, publishing, installation and performance, the public outcomes of the archival process include The Incomplete Poem, a physical collection of garments featuring shanzhai lyrics, and The Endless Garment, in which the collected lyrics are transcribed in various ways including as books, temporary tattoos and through collective readings. The duo also hosts an Instagram account fuelled through open submission, amassing material, hybridising it into published and wearable forms, all while responding to varying host institutions. Shanzhai Lyric is part archive and part itinerant actor, using language to identify with contemporary modes of distribution so as to run against the grain of those same structures.

The traditional European archive has a dialectical character; it forms an image of infinite variety while preserving material finitude. Inside the archive one drifts text to text, object to object, link to link; guided by curiosity and proximity, one turns over referents from but no longer of the outside world. Shanzhai Lyric’s experimental archival practice unpicks this interior/exterior dichotomy. ‘We collect and collate these poetry-garments both physically and digitally from markets around the world and through online submission,’ Lin and Tatarsky explain. ‘We take up the task of finding different ways to activate this collection so that it is never stagnant but always moving, shifting, growing, shrinking.’ The porousness of Shanzhai Lyric’s archival form and method is unbound from arbitrarily policed divisions of material and immaterial and that which belongs to the canon and vernacular. If standard archival procedure encourages splitting, categorisation and hierarchical order, Shanzhai Lyric funnel their material through pathways they find and create.

Practices of fugitivity and a sense of mobility bind the multiple threads of the project, and are at the core of Lin and Tatarsky’s theoretical and political concerns. The pair place the project in a lineage of Marxist-feminist critical theory and a decolonial approach to language, or, more bluntly: ‘We want to celebrate shanzhai influence and the alternate values set forth by a model of making that thinks differently about ownership and theft.’ Through their tactics of reframing, editing and ventriloquism, Shanzhai Lyric question the naturalisation of rights to property, particularly when the object of property is something as mutating as language or as mutable as the signifier of a brand. Why does a sportswear company own the name of the Ancient Greek goddess of victory, or an online shopping giant own the name of the world’s largest river? Why should a long discredited Victorian colonialism still dictate the global use of the English language? And through which social pedagogies have we been persuaded and cajoled into propping up the dominant and exploitative forms of capitalism which enable and perpetuate these situations?

Recently, the Covid-19 pandemic halted international travel and commerce as well as local business, the interruption to daily life bringing with it a racialised discussion of health and hygiene which fed xenophobia and worsened diplomatic and trade relations between the US and China. Subsequently, the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police has sparked widespread protest against anti-black violence and police brutality. It is worth noting that the police who killed Floyd were called after he allegedly tried to pass counterfeit money, a forged $20 bill. Mediated by digital communication, protesters in the US have been sharing and borrowing tactics of street blockades and counter-surveillance from the long-standing pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong – even in lockdown, everything flows. The destruction of property has become a contested aspect of these protests. Reactionary critics of the demonstrations have described ‘looting’ as an apolitical and criminal act. While those on the street, and in support, claim it as a direct attack on the binds of property, power, class and race which subjugate and pulverise those who fall outside the narrow group of people capital truly privileges.

The whiplash response of those who would argue for the protection of property over the protection of life has underscored the political commitment of Shanzhai Lyric and their relationship to property, as Lin and Tatarsky elaborate: ‘“Looting” was a racist term used to characterise revolters in colonial India in order to justify violent repression by the British Empire. In our present context the term is being applied similarly, to justify state violence against protesters. We continuously celebrate these forms of theft; recognition of these acts as political, philosophical, and artistic acts of rebellion is at the heart of our research.’

Alexandra Symons Sutcliffe is a writer, curator and producer based in London and Berlin.

First published in Art Monthly 438: Jul-Aug 2020.