Feature

The Art of Denial

Bob Dickinson on artists who have engaged with the legacies of trauma

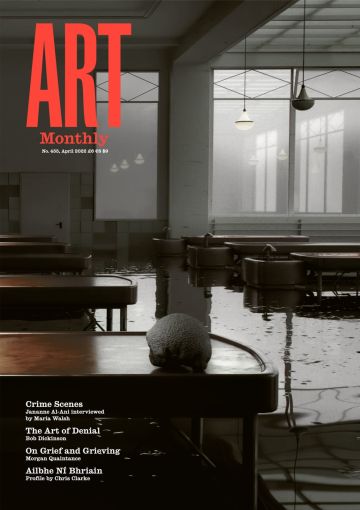

Marisa Cornejo, La Huella (The Footprint), 2013

Bob Dickinson discusses the ways in which artists have attempted to engage with the legacies of trauma to counteract decades of denial and untruth, of historical revisionism, distortion and political suppression.

On 10 March, the Russian news agency TASS quoted foreign minister Sergey Lavrov’s statement that ‘we have not invaded’, citing Vladimir Putin’s earlier description of the multipronged Russian incursion, in a televised address on 24 February, as a ‘special military operation’ aimed at protecting people in Ukraine’s Donbas region ‘who have been suffering from abuse and genocide by the Kiev regime for eight years’. In reality, the invasion dates back to eight years ago when Russian-backed separatists and Russian troops took the Crimean peninsula from Ukraine in response to the overthrow of Russia-leaning President Viktor Yanukovych.

All wars produce untruths and distortion. At the same time, war takes place in an aesthetic-historic context. The return of a war that threatens to bring catastrophe to all states bordering Russia and beyond suggests that now is an appropriate time to reflect on contemporary artists’ responses to examples of denial that propel the rise of nationalist and imperialist politics that have led us here, particularly in post-communist countries such as Russia and Ukraine, where nationalism finds a base in a pre-existing, nostalgic aesthetic. Something bigger, from an even more murderous time, becomes reactivated and finds new forms to which memory can attach itself.

In Ukraine, this aesthetic – a Soviet-made, modernist one, along with the promise it once offered – is explored in the work of Nikita Kadan. Responding to the 2013 Euromaidan uprising that led the following year to the Revolution of Dignity and the overthrow of Yanukovych’s government, Kadan produced the sculptural installation Hold the Thought, Where the Story was Interrupted, 2014. The work consists of a futuristic-looking set, consciously based on Soviet modernist memorials to war, which contains a stuffed deer, photos and objects recovered from a museum in Donetsk that was wrecked in a missile strike. Dragged from history, the promise of Modernism contained in this work threatens to turn in on itself and crush the onlooker, while the kitsch and once-reassuring world of the local museum seems to stare back through the glass eyes of the long-dead animal.

Kadan’s preoccupation with memory may seem to suggest the psychological difficulties of emerging from a post-Soviet world, which was suffused with monuments to heroic sacrifice and communist determinism. But in Ukraine, that Soviet past was also shaped by cover-ups and disinformation from a succession of controlling forces, which also included Nazi and Polish nationalist elements. Addressing the manipulation of memory, Kadan’s 2016 series of drawings ‘The Chronicle’ is based on historic photographs that were doctored by different regimes, showing victims of the Lviv pogroms of 1941, the Volhynia massacre of Polish villages in 1943, victims of the NKVD and the Nazi occupation. Another work in charcoal, The Spectators, 2016, is also based on historic photographs, originally prepared by Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova for their 1934 book Ten Years of Uzbekistan. Later that decade, following the denunciation of various officials who had been included in the book, Rodchenko brushed ink over their faces in the original copy he owned, and these inked-over images are the ones Kadan drew, thinking of them as ‘spirit spectators’ to historical revisionism.

Media-aided denial and distortion do much to aid a wide sense of negation about certain events that are planned, or which have already happened, during any war. But all wars kill, often illegally according to international law, for instance by targeting civilians or ethnic groups, or using certain types of proscribed weapons. Examples of such illegal attacks seem already to have occurred in Ukraine. It can take time – decades – to follow the trails of evidence of such acts, which can involve literal cover-ups including mass burials. Following the break-up of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s and the wars that ensued, notably in Bosnia and Kosovo, it has taken years, in some cases, to recover the bodies of many of the victims of these wars, victims whose deaths were frequently kept secret, or whose disappearances were denied. Much was said in 2015 about Bosnian artist Sejla Kameric’s work Ab uno disce omnes, 2015 – a title which means ‘from one example can be learned a general truth’. The artwork consisted of a silver refrigeration unit of the sort normally used in morgues, and was shown at the Wellcome Collection’s ‘Anatomy of Crime’ exhibition, which focused on forensics, a science that has been so important in identifying the victims of war crimes denied by the perpetrators.

Belgrade-based artist Vladimir Miladinović could perhaps be said to have developed a very personal relationship with such recorded evidence by exhaustively copying newspaper and magazine reports or official documents to images in ink and paint. His 2015 exhibition ‘Free Objects’ detailed the descriptions of objects that were recovered along with the bodies of 744 Kosovo Albanians discovered in 2001 at a special Serbian anti-terrorist police training centre in Batajnica, near Belgrade. The bodies had been removed from their original burial places in Kosovo and transported in trucks to conceal the evidence of war crimes committed there, before being burned and reburied. The additional ‘free objects’ referred to in the work’s title included personal items and some body parts, all of which disappeared later, leaving only the written documentation. Miladinović copied these bureaucratically recorded details, which contained numerous examples of words like ‘hair’, ‘wristwatch’, ‘cigarette holder’, ‘lucky charm’, ‘wedding band’, ‘set of beads’, ‘wallet’ and, more than any other object, ‘projectile’ – read bullet. Another collection of painted documents by Miladinović, The Notebook, shown at Eugster in Belgrade in 2020, is based on pages from the secret diaries of General Ratko Mladić, the Bosnian Serb who had supervised the siege of Sarajevo between 1992 and 1996, and the genocidal killing of over 8,000 Bosnian Muslims at Srebrenica in 1995. The diaries were discovered in 2010, hidden behind a fake wall in a former safe-house used by Mladić before his capture in 2011 and subsequent trial at the Hague for genocide and crimes against humanity. In 2017, Mladić was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment – the diaries were part of the evidence that convicted him. Still, many of the newspaper headlines in Serbia, reporting on the trial, continued to hail Mladić as a hero.

Denials, of course, are not solely the speciality of former communist countries, or even of those, like Yugoslavia, which were not aligned with either the USSR or the west. The US and many western nations have equally damning histories of imperialistic denial, reinforcing their policies in relation to areas as far apart as South America and Africa during the 20th century and beyond. Chilean artist (and AM patron) Alfredo Jaar’s project Searching For K, 1984, is a series of photographs recording the travels of Henry Kissinger, US secretary of state under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Notoriously, in 1973 Kissinger received the Nobel Peace Prize in for his role in the negotiation of the ceasefire with North Vietnam, as part of the Paris Peace Accords – two members of the Nobel committee resigned in protest. In the artwork by Jaar (Interview AM342), each image identifies Kissinger by surrounding his head with a red circle. The work’s appearance in Germany in 2012, in the exhibition ‘The Way It Is: An Aesthetics of Resistance’ at Berlin’s Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst, took place in collaboration with the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), whose purpose is to counter injustice with legal interventions. The work was accompanied by advertisements in a number of Berlin newspapers to ‘Arrest Kissinger!’ printed in languages spoken by people affected by Kissinger’s brand of ‘shuttle diplomacy’ and ‘realpolitik’, including Spanish, Vietnamese, Khmer, Portuguese and Timor. It was an approach that insisted on the continued importance of bringing Kissinger to justice, and involved a team of lawyers brought on board to ensure a prosecution. However, as the ECCHR pointed out, ‘the laws in place when his crimes were committed did not allow for universal jurisdiction in criminal cases, as would be possible today’. In particular, justice is still needed in relation to events Kissinger caused during the CIA-backed Operation Condor, which included huge numbers of assassinations, kidnappings and disappearances under right-wing dictatorships in Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia and Chile, Jaar’s country of birth.

One of Jaar’s 2008 works uses a direct quote from Kissinger’s lips: Nothing of very great consequence. The work takes the form of a projected photo showing the transcript of Kissinger’s telephone conversation with Nixon on 16 September 1973, four days after the coup in Santiago which overthrew the government of socialist President Salvador Allende, supported by the CIA at Kissinger’s behest. ‘The Chilean thing is consolidated,’ Kissinger continues, ‘And of course the newspapers are bleeding because a pro-Communist government has been overthrown.’ What Nixon was interested in confirming, a few lines later, was that ‘our hand doesn’t show on this one’. The fact that audiences are faced with this dialogue in scripted form shows what Jaar does best in his work, which is to ‘speak between the lines’, as he himself puts it. The actual words uttered by Nixon and Kissinger, including their sly efforts to safely cover their own tracks, also include Kissinger’s utterly banal wish to go to a football game that afternoon, while at the same time in Chile hundreds were being arrested, tortured and killed. These two major politicians of their day appear small-minded and cynical, while we are simultaneously but silently reminded of the victims of the coup.

The aesthetic context in which Jaar works often reflects on media reporting and the resulting way it can make a given event or statement appear either spectacular, glib or downright untrue. As part of his Rwanda Project, 1994–2010, Jaar produced We wish to inform you we didn’t know, 2010, taking a quote from another US president, Bill Clinton, while he attempted to excuse the West’s failure to intervene in the Rwandan genocide, in which between April and July 1994 approximately 800,000 people died, mostly Tutsi tribespeople. The context in which the artwork was conceived was darkly contemplative, using images of victims and skeletal remains, while Clinton’s inadequate words can be heard, failing to overcome another truth about his form of denial – Clinton’s ‘not knowing’ equating with not really seeing. Jaar’s piece underlines the racism that underpinned all lack of action by the West.

The biggest event in the past hundred years to which the act of negation has been applied is the Second World War Holocaust, outlined in detail definitively by Deborah Lipstadt in her 1993 book Denying the Holocaust. But even deliberate acts of remembrance or commemoration, some 70 years after the events, can give rise to concerns about the extent to which we can still feel genuine shock and revulsion at what happened. This is not to say that repeated and established forms of memorialisation are somehow false, but that they could perhaps sentimentalise, trivialise or even normalise the essential criminal nature of the Holocaust, and attribute it to the notion, often applied to it, of some ‘evil’ force. Questions surrounding these issues arose in 2015 after the opening of the controversial exhibition ‘My Poland: On Recalling and Forgetting’, at Tartu Art Museum in Estonia, which attracted criticism by several groups, including the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, because of the inclusion of certain artworks such as two videos by Arthur Żmijewski (Interview AM333). These were Berek: The Game of Tag, 1999, filmed in the gas chamber of Stutthof Concentration Camp, near Gdansk, in which naked actors play prisoners who are seen laughing while enjoying a children’s chasing game, and 80064, 2004, in which a 92-year-old survivor of Auschwitz, Josef Tarnawa, is persuaded by the artist to renew his concentration camp tattoo, whose number provides the film’s title. Perhaps the shock expressed by some visitors and critics on seeing these artworks was more horrified and heartfelt than might have been the result of simply learning about the Holocaust through reading, visiting museums, watching documentaries and other established educational methods. My main worry is that, when it comes to the more cynical viewer, I do not know if the effect of these films would push them towards accepting the reality of the Holocaust, or titillate them and lead them into a frivolous direction of thought that might reach a denialist conclusion. But the show at Tartu also included more contained, better-conceived work, including Yael Bartana’s Mary Koszmary (Nightmare), 2008, part of her ‘Europe Will be Stunned’ trilogy (Interview AM450), in which the real-life journalist Slawomir Sierakowski acts out a political speech addressed to an audience of boy scouts in an old, overgrown public stadium (reminiscent of the setting for more than one totalitarian film by Leni Riefenstahl). In his speech, Sierakowski appeals to the 3,300,000 Polish Jews lost in the Second World War to return to Poland. The idealism behind this wish, set within the utopian framework of certain types of 20th-century cinema from the USSR as well as Germany and elsewhere, is focused on this attempt to unblock a haunted national imagination. Sierakowski has spoken about Poland’s condition in terms of ‘manic defence’ – that form of behaviour described by psychiatrists as being similar to denial in covering up melancholia about the past. So, in this film, aesthetics arguably forms a route through which that radical shift might take place.

Denial abuses the mind and the body of the individual as well as the political wellbeing of a nation or region. The invasion (which according to Lavrov is not an invasion) of Ukraine, with its besieging of cities and targeting of civilians, has rapidly seen the reduction for its victims to the condition described by the philosopher Giorgio Agamben as ‘bare life’, just as it was for the victims of torture and for the ‘disappeared’ during the ‘dirty wars’ of dictatorial governments in South America during the 1970s. This ‘bare life’ state, in which a sovereign power denies to its citizens what are previously established rules and safeguards, is eerily realised in some of the work of the German-Uruguayan artist Luis Camnitzer (Interview AM438) in his 1970 installation Leftovers, a set of 80 rigidly stacked cardboard boxes that seem to be oozing blood, and from the ‘Uruguayan Torture Series’, 1983–84, a set of 35 photo-etchings of objects and parts of the body with sinister subtitles written beneath, for instance a pair of pliers that grips what appears to be pubic hair accompanied by the words ‘the tool pleased him’, while a human hand squeezing against the bottom of a brick wall is entitled ‘Measuring helped him appropriate the space’.

Chilean-Swiss artist and contemporary dancer Marisa Cornejo explores the ways in which the negation or denial of human rights, or of human existence, has a profound emotional impact on subsequent generations. Cornejo’s father Eugenio, an art teacher, was arrested and tortured by the Pinochet regime’s security forces in Chile and later exiled, moving with his family to Bulgaria and Mexico, where he died. He suffered from post-traumatic stress but received no reparation from the later democratic Chilean governments that followed on from Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. His daughter’s work internalises these stresses and injustices, particularly in the way she worked through several iterations of her performance La Huella (The Footprint), 2013–15. The artist has described how this work had its origins in a dream in which her father invited her to make prints from old lino cuts originally engraved by him in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, out of scrap linoleum he found in a pile of rubbish, and how these once-lost and neglected lino sheets became – citing Walter Benjamin – ‘auratic relics’ for her. The work mixed shamanistic practices learned from her time in Mexico, and physical printing, using different parts of her body to apply pressure onto the much-travelled lino sheets. Returning to Santiago, some performances took place at a location she had good reason to fear: the Estadio Nacional, or National Stadium, a place where her father was among the hundreds of men and women interned between the day of the coup, 11 September, and 7 November 1973. It is now known as the Victor Jara Stadium, named after the left-wing activist, singer and songwriter who was tortured and killed there.

Marisa Cornejo associates herself with the transmodernist movement in philosophy. She identifies her experience with that of refugees and stateless people everywhere. As the current war in Ukraine unfolds, another refugee crisis has also broken out, no doubt containing within it many thousands of examples of people suffering trauma through mental as well as physical damage. Many countries are waiving visas and welcoming them in vast numbers. But, at the time of writing, regarding the urgent state-level support these latest victims of war require, the UK government seems very much to be in denial.

Bob Dickinson is a writer based in Manchester.

First published in Art Monthly 455: April 2022.