Review

The Double: Identity and Difference in Art Since 1900

Richard A Kaye encounters the magic of the double in this inspired exhibition

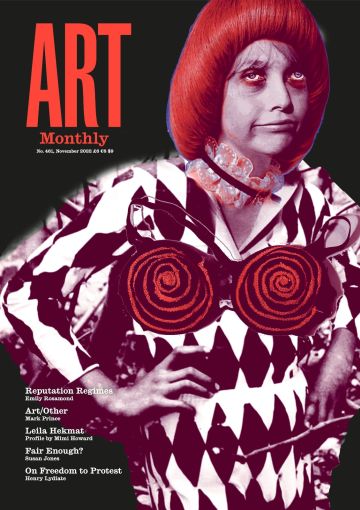

Rashid Johnson, The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Emmett), 2008

As a student at Smith College in 1955, Sylvia Plath elected to write her senior thesis on the figure of the double in the fiction of Fyodor Dostoevsky, a paper entitled The Magic Mirror that explored fictional scenarios in which ‘the evil or repressed characteristics’ of an individual overwhelms ‘its master’ and imperils the protagonist.

One might have thought, as Plath evidently did, that the figure of the double was primarily a 19th-century phenomenon, given mirrored embodiment in novels such as Dostoevsky’s The Double, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, those foundational models of creepy double-ness that were then given the imprimatur of science with Sigmund Freud’s turn-of-the-century ‘discovery’ of an unconscious that bedevils a conscious self and then validation as a crucial myth in an influential 1925 study The Double by Freud’s disciple Otto Rank. However, as demonstrated in the eye-opening, intensely conjunctive exhibition at Washington, DC’s National Gallery, curated by the museum’s curator of modern art, James Meyer, the double has haunted 20th- and 21st-century art. Plath herself makes an appearance here with her gouache-and-ink Self-Portrait in Semi-Abstract Style, c1946–52, the young poet depicted as bifurcated between a (presumably naughty) platinum blonde and (presumably good-girl) brunette, a brooding meditation on cruelly competing mid-century American expectations of proper womanhood. That doubling might evoke a haunted irresolution about the past comes across in the exhibition’s juxtaposition of Arshile Gorky’s two versions of his iconic The Artist and His Mother, c1926–42, drawn from a photograph, in which a shift in colouring (from darker hues to lighter) arguably bespeaks a changed attitude – or an obsession – over a lifetime.

This wide-ranging exhibition, 12 years in the planning and reflecting the work of 101 modern and contemporary artists, is absorbed in far more than split psychological states, however, as history, politics, formal challenges, queer, feminist, ethnic and racial identities, not to mention optical experiment, keep intruding. The exhibition begins with Glenn Ligon’s politically freighted neon-and-paint Double America, 2012, in which a duplicate of the word ‘America’, one in bright white lettering, misspelt, rests on an inverted one, also misspelt, forges a rumination on gleaming patriotism and its troubled opposite. Rashid Johnson’s The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Emmett), 2008, with its doubled portraits of an African-American male, is more intriguingly ambiguous, evoking not only photographs of the former slave-turned-antislavery crusader Frederick Douglass but, with the parenthesised part of its title, the 1955 torture and murder of the Mississippi boy Emmett Till: African-American history bifurcated by (or tragically conjoined with) 19th-century abolitionist heroism and 20th-century racist violence. Felix Nussbaum’s Self- Portrait with Jewish Identity Card, c1943, depicts a terrified, cornered artist (who died in the Nazi death camps) staring into the eyes of a viewer (or persecutor), the doubling playing out on the canvas and implicating the onlooker. Even what might seem Gorky’s wholly personal self-portraits with his mother are saturated in historical crisis, Gorky’s mother having died of starvation (a death the artist witnessed) during the 1919 Armenian genocide.

Structured by four rubrics, Seeing Double (a comparison of like with like that entails a perception of both likeness and unlikeness), Reversal (inverted, mirrored, rotated or upside-down forms), Dilemma (a choice between two perceptual or cognitive options) and the Divided and Doubled Self (divided or shadowed selves or personae, sometimes expressed in fraternal, romantic or artistic pairings), ‘The Double’ offers some striking, unusual and original unions and disunions. One notable aspect of the exhibition is that, while it rather passingly acknowledges Modernism’s investment in doublings with works by Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian and Pablo Picasso, the heart of the exhibition lies in Abstract, Abstract Expressionist, Pop and Minimalist Art, movements with divergent aesthetic aspirations that here are thematically united (Meyer is the author of the fine 2001 study Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties). Barnett Newman’s tremulous Onement 1, 1948, which Meyer calls a breakthrough work in the artist’s career, recalls Mondrian, even as its bifurcating line – red paint on a piece of masking tape that Newman called a ‘zip’ dividing the canvas into two sections – speaks of a human gesture missing in Mondrian’s cooler canvases. Mondrian’s Composition (No. 1) Gray-Red, 1935, is juxtaposed suggestively alongside White, Black, Red, and Gray, 1932, by the Anglo-Jewish queer artist Marlow Moss, self-exiled in Paris where she drew Mondrian’s admiration.

Jasper Johns’s Two Flags, 1962, and Robert Rauschenberg’s Factum I and Factum II, both from 1957, apart and together seem to demand that the viewer seek out multiple differences in similar images, a paradox explored elsewhere in ‘The Double’ as we are invited to see the variances between supposedly like and like. Warholian doubles are everywhere, among them Andy Warhol’s 1963–64 doubled newspaper image of an ambulance crash (one image decorously blocking out the crash victim’s face), his doubled-image of Edie Sedgwick from his film Outer and Inner Space, 1965, the macabre Self-Portrait with Skull, 1978, The Shadow, 1981, a photographic screenprint depicting a red-hued Warhol against his greenish shadow, and Christopher Makos’s black-and-white photograph of the androgynous, bewigged Pop artist in jeans, Lady Warhol, 1981. Other standouts are Eva Hesse’s Metronomic Irregularity I, 1966, with its crossed wires evoking a chiming musical unity, and Roni Horn’s One More Things That Happen Again, 1986, a duo of sleek identical copper cones.

Diane Arbus’s familiar Identical Twins, Roselle, N. J. 1956 is on display, as inevitable a choice as Alighiero Boetti’s Gemelli (Zwei), 1974–75, although Arbus’s uncanny naturalism could not be more unlike Boetti’s playfully staged, pastoral dream of male twindom, with its sneaky intimation of an incestuous bond in the linked hands of its dapper pair. Images of same-sex couples abound, including Man Ray’s 1922 photo of Alice B Toklas and Gertrude Stein at home (a rather diminished pair amid the couple’s modern art collection) and Gilbert & George’s blurry (so as to suggest a likeness between the men denied in reality or perhaps to produce a drunk-fuelled blurriness) video Gordon Makes Us Drunk, 1971. Without too much didacticism, the show reminds us of the inherent queerness of the double (from the late-Victorian Dorian Gray to the 1970s trend of the gay male urban ‘clone’ and well beyond) as it questions just how ‘same’ the participants in same-sex couplings really are. A different register of the uncanny is conjured in Giuseppe Penone’s Reversing One’s Own Eyes, 1970, a sequence of six slides of the artist as a young man moving towards the viewer to reveal that he is wearing contact lenses made of tiny mirrors, an unsettling image that Meyer decodes in his essay in the exhibition’s catalogue as suggestive of the ‘Unheimlich that Freud ascribes to both an encounter with one’s own double and the unease we feel when forced to imagine the possibility of our own blinding’.

Plath, who began work on a novel entitled Doubletake, then retitled Double Exposure (a semi-autobiographical work that has never been found but which she described in a letter as concerning a ‘wife whose husband turns out to be a deserter and philanderer although she had thought he was wonderful & perfect’) seems to have seen the whole issue of the double as reflecting an essential death wish. Through the double, Plath explained in her college thesis, the ‘desire for oblivion is expressed’ in the divided self’s ‘tendency to hide in shadows and in back hallways; it develops into a strong wish for death’. It is a predictable Plathian formulation – although surely Plath knew that the back hallways of the self could be intriguing places, hence the ‘magic’ in the title of her thesis. In any case, it is the magic of the double that is given complex, vivid life in the National Gallery’s inspired exhibition.

Richard A Kaye is professor of English at Hunter College and Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

‘The Double: Identity and Difference in Art Since 1900’, National Gallery, Washington DC, 10 July to 31 October 2022

First published in Art Monthly 461: November 2022.