Feature

Art Engagement

Lizzie Lloyd asks whether an artist needs to describe themselves as socially engaged in order to engage socially

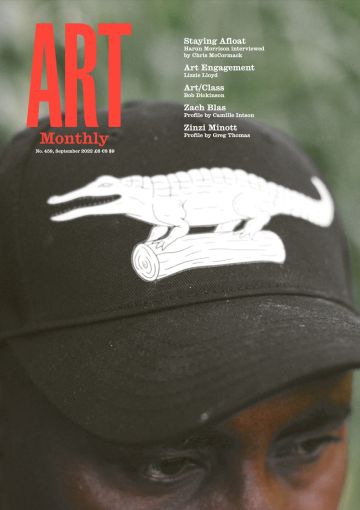

Suzanne Lacy, The Circle and the Square, 2015–17

There is much barely disguised cynicism surrounding funding models in the arts that are largely predicated on the successful demonstration of public engagement. Yet, the familiar liberal values which contemporary arts industries generally purport to uphold presuppose that we should all be interested in opening up the arts to make them more accessible and diverse. It would be quite a challenge to find an artist who admitted to not being for such inclusivity, let alone to being actively against it. It is possible to demonstrate this pro-engagement political leaning not only by making and exhibiting artwork with a more socially diverse audience in mind, and by using a more diverse roster of artists, but also by developing artworks in participation or collaboration with people who don’t necessarily identify as artists or as creative professionals. Things are not straightforward, however, and it is telling that Claire Bishop’s critique of this kind of work still rings true, after nearly 20 years: ‘collaborative practices are automatically perceived to be equally important artistic gestures of resistance: there can be no failed, unsuccessful, unresolved, or boring works of collaborative art because all are equally essential to the task of strengthening the social bond’. The assumption remains that work made with other people is, almost by definition, an act of social goodness, moral altruism and political upstanding. But how these artworks communicate, not just what they communicate, needs greater attention.

There are various terms for this kind of art-making that overlap in various ways – social practice, socially engaged art, relational aesthetics, participatory or collaborative practice, dialogic art etc – but I’m not convinced that any of these terms are particularly helpful. Partly it is a question of implication: does an artist need to term themselves socially engaged in order to engage socially? To do so runs the risk of pitting one type of art-making against another. In her 2018 interview with Jennifer Higgie, Sonia Boyce (Interview AM415) said, ‘After I made the large work on paper, She Ain’t Holding Them Up, She’s Holding On (Some English Rose), 1986, I felt that there was nowhere else to go: I had come to a full stop. That is why I moved into a more performative, social practice.’ Boyce went on, ‘The constant in my work has always been a discussion around gender, race and sexuality; it was never just about me but, more broadly, about the role and representation of the black female figure.’ Following this argument, drawing (and by implication painting and other ‘solo’ studio-based work) is deemed introverted, limited by the selfhood or lived experiences of its author, resulting in a creative, conceptual and even social cul-de-sac. Performance and social practice are characterised (rather idealistically) as being open and offering greater possibilities for universal significance. But to pit the private against the public, the personal against the collective, in this way is surely an oversimplification. Boyce’s early work could easily be defined as autoethnographic, a method that Heewon Chang defined in 2008 as sharing ‘the storytelling feature with other genres of self-narrative but transcends mere narration of self to engage in cultural analysis and interpretation’.

In fact, the argument about studio practice and social practice can be made the other way too. The reality of developing a socially engaged project is complicated, messy, flecked with conflict (and the polite aversion to conflict), negotiation, the authorship of the artist diluted by necessary adaptations and compromises. It contrasts with the image of the artist alone in their studio making their own decisions, following their own self-determining logic. But artist Harun Morrison (Interview p1), for example, is deeply suspicious of setting social practice ‘in opposition to studio practices, which are then perceived as being more free and more autonomous’ to create a false dichotomy. ‘That binary’, concludes Morrison, ‘shouldn’t exist.’ Such binaries are founded on rigid distinctions between the personal and the universal, individualism and collectivity, control and freedom, process and outcome. One means of overcoming this binary is to conceptualise social practice as going beyond doing social good. Suzanne Lacy, often considered a pioneer of social practice, said her aims for The Circle and the Square, 2015–17, were for it ‘to operate between being very well situated and engaged in the community and having an equal presence in a museum’. Social practice should exist and be considered of value, both in the process of making the work for the community of people involved and as an artwork in its own right, able to hold its own.

Elsewhere, Morrison has advocated for more fluid, flexible and organic approaches to art and exhibition-making which might impact how socially engaged work is both conceived and executed. In the publicly available Googledoc ‘A Thousand Years of Zoom: Rough Notes & Anecdotes on Exhibition-Making on Lockdown’, 2021, he writes: ‘A porous exhibition, an elastic exhibition is one indistinct in its beginning and closure, that’s not determined by funding structures, or over articulated before it has begun, because it’s understood that it may morph into something else, some elements may be fixed others not.’ Morrison, then, is against predetermined definitions and conceptual frameworks that are the stuff of arts funders and organisations. Instead, he calls for work to be developed with a ‘disorganisation [that] would have no investment in repeating its exhibition logics for the convenience or brand-building and might re-constellate itself around the specific needs, desires and provocations of those invited to work with them’. This re-constellating feels like it might equally be the preserve of artists who chose to develop work with and alongside publics, which Morrison also does as one part of the collaborative practice They Are Here, alongside Helen Walker. At stake in working around ‘the specific needs, desires and provocations’ of other people are a myriad of tensions, especially when the requirements of funding bodies, for example, are predicated on an expectation that artists and institutions perform their ‘outreach’ credentials.

In my discussion with Morrison on this matter he considers the different approaches by which socially engaged artwork comes into being. One is artist-initiated, in which an artist identifies a specific group of people with whom they want to work on a particular project; another might be an arts organisation with a long-standing relationship working with a specific group (Cubitt artist-run cooperative and gallery, which works with Mildmay extra care, for example). A third, and perhaps more common approach, comes about as the result of gallery education teams identifying a group of people alongside whom they commission artists to develop work. Clearly these models overlap in various ways and can result in more and less successful outcomes, but the spirit by which these projects come about has real implications for their social, political and artistic value, argues Morrison. It goes back to expectations brought about as a result of funding models: if public engagement is expected from work that is publicly funded, will that engagement be central, genuine and sincere? Or will the engagement be merely a necessary hurdle to secure funding, executed as a begrudging afterthought and the preserve of the learning and education or engagement team rather than the curatorial programme? The disconnect that so often exists in arts institutions between the prestigious curatorial programme and the often subordinate events programme is a major stumbling block and a tension felt by many in the sector.

There are other issues at stake in such projects, however, even if the founding intentions of the artist are well meaning. How, for example, should an artist deal with the material they generate through the social aspects of the work’s making? How is authorship shared and acknowledged? How can this social engagement be transformed from being integral to the process to being integral to the outcome too? These issues are crucial in order to communicate the nature of the engagement with audiences beyond those involved in the development of the work. How can such engagements be opened out, affect and provoke thought in publics beyond those directly worked with? Given that the vast majority of art’s audiences have not experienced the artwork for themselves, the matter of how such work presents and communicates beyond the life of the making of the project or the unfolding of the event is vital. Here again, the matter is not clear cut. One line of argument runs that to document the work is to commodify it, to objectify it in ways that run counter to the anti-capitalist spirit that often features in this kind of work. These questions do not just have artistic or political but also ethical implications (not to mention the legal question of creative ownership): how do artists ensure that the work that comes out of these social engagements is sensitive, respectful and productive for all parties? The risk of social or psychological exploitation, condescension or pity are very real when working with certain communities.

In ‘Radio Ballads’ – which showed concurrently at the Serpentine and at Barking Town Hall and Learning Centre this spring – Sonia Boyce, Helen Cammock, Rory Pilgrim and Ilona Sagar made films developed through relationships with people in social care and community groups in one of London’s most derived areas. This project, incidentally, was initiated and developed by artist-curator Amal Khalaf, who is projects curator at Serpentine and director of programmes at Cubitt. As Maria Walsh pointed out in her review of the shows (AM456), the artists involved each navigated the ethics of documentation and representation in different ways: Cammock’s shots of community workshops were framed in a ‘loosely decentred way’, Walsh writes, rather than offering a ‘birds-eye view’. This footage, made up of fragments of bodies and incidental, peripheral details, demonstrates an effort to avoid romanticised and self-congratulatory footage of disadvantaged people being brought together to do ‘wholesome’ creative activities. Meanwhile Boyce, Walsh argues, steers clear of objectifying traumatised figures by avoiding a single central story on to which the viewer might pin a pitying gaze, filming participants from the front or from behind depending on how they feel most comfortable. In both cases Cammock and Boyce find ways to complicate viewers’ access to the people and their stories recorded on camera.

The question of telling stories appears almost to have replaced the emphasis on building social bonds, which Bishop identified as social practice’s greatest motivator: how can socially engaged art ensure that the stories of others are not only told but, even more importantly, are really heard? In my recent conversation with Lucy Wright, social producer at Axis, she said, in respect of socially engaged art, that ‘the story is the main currency’. She was referring to the work of Leila Jancovich and David Stevenson, which challenges ‘a cultural landscape that is not conducive to honesty or critical reflection about failures’ in which ‘feel-good’ narratives overstate the impacts and successes of participatory work. It’s not hard to figure out why this might be, when artists’ (and researchers’ more broadly) future funding is built on the evidenced successes of previous projects. The phrasing sits uneasily for other reasons, however: in describing the story as ‘currency’, Wright openly alludes to the capitalisation of embedding the lived experiences of others, however well meant, within the frame of the work.

The issue is not with storytelling per se, but with how stories are told and to what end; in the right hands, ‘storytelling’, as Hannah Arendt wrote, ‘reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it’. Eelyn Lee, in a film entitled Futurist Women developed with the Barbican in 2018, brings together a desire to hold real-life stories but also to go beyond them. Developed with survivors of domestic violence, the work involved Lee organising a series of costume-making and poetry-writing workshops. The results of these workshops informed and became part of the final outcome, a film set in the otherworldly context of Rainham Marshes made up of dreamlike footage in which the camera lingers softly on swathes of reeds swaying in and out of focus on the breeze and bleached out sunlit marshland. The film pans across the bodies of Lee’s women participants-cum-collaborators, now filmed in positions of power and resplendence, dressed in their costumes of billowing fabrics, their faces part-covered by more fabric or make-up, face paint or elaborate headdresses. At times they hold your gaze, at others they look proudly to the middle distance. Different female voices read a poem written by Annetha Mills, one of the participant/collaborators, set to an ethereal ambient track of tinkling chimes, environmental birdsong and the breeze. The splendour of this work by no means trivialises Lee’s collaborators’ suffering in the name of aesthetic pleasure, however; it ensures that the realities of the traumatic experiences of survivors are not just used as a device to raise awareness or arouse sympathy, but also that art is used as a means of transforming painful realities into imaginative, empowered possibilities and forward-looking futures.

The risk of artwork that works with disenfranchised communities, as I discussed previously in relation to art in public spaces (‘Art and Place’, AM439), is caught up in elitist rhetoric around cultural and social betterment – what Janine Francois has called ‘missionary politics’. How then do artists find ways to work with groups that might not necessarily identify as part of an art community? How can the visible outcomes of projects that stem from the collaboration and participation of disadvantaged or marginalised groups steer clear of this kind of self-congratulatory cultural and social superiority? Because when it comes to representation, the power shifts between who is being represented (passive) and who is representing (active) are key. Artist Beverly Bennett, following a year-long project with Towner Eastbourne in which she worked remotely over lockdown with a group of people to offer a network of support, care and connection through digital technology, presses back against the pressures to make visible her work with groups. I suspect this is, in part, a weariness with the burden of visibility for marginalised bodies being rendered ‘hypervisible’ by institutions, objectified, in order to perform inclusivity to meet their equity, diversity and inclusion strategies while remaining, to all intents and purposes, exclusive. The only visible, publicly accessible outcome of Bennett’s project is a commissioned text by Chris Fite-Wassilak, who was not part of the group but whose writing took as a jumping-off point material generated and shared by the group. Esther Collins, head of learning at Towner Eastbourne, who commissioned the text, describes it as a means to get beyond writing as a description or review of the event. Instead, she gave Fite-Wassilak the brief of using ‘the feel of the space Beverley held as a place to start’. In this equation, material generated through a participatory experience remains publicly invisible, unevidenced, indirect – a point of departure for another connected but different artwork.

It is not by chance that I reference Bennett’s project. I came to know her recently following a performance workshop I co-facilitated with Katy Beinart and Benjamin Owen. The event at Towner was aimed at artists or people with an active practice of working with communities. It developed, in part, out of a project that Beinart and I have worked on called Acts of Transfer: Sharing Socially Engaged Art. Through Acts of Transfer we worked with Eelyn Lee, Harun Morrison and a roster of other artists and project participants, returning to socially engaged artworks from the past to think about, amongst other things, their archival legacies. What, we wondered, is their afterlife? How do we capture the feel and not just the content of such projects to communicate beyond those directly involved?

The matter of how we negotiated documenting the Towner event is revealing. As an event designed for our peers, what ‘story’ would our documentation tell? How would we ensure that our documentation aligned with the ethos and critical discussion of the day whilst also satisfying the requirements of the institution supporting our work to capture its investment in us, visually, and at the same time encouraging its future support for other work of this kind? Given our concerns at the instrumentalisation of socially engaged work, and the tendency to uncomplicatedly idealise the processes of collaborative working, this negotiation felt vital. After some discussion we opted for a combination of democratic documentation and official photography. We encouraged our participants to upload their own photographs from the day to a live document, allowing them to pick out incidental details from the day that they found noteworthy. This partly worked. After an initial flurry of uploads, participants became absorbed in the activities set, and the conversation these generated, and we mostly rather forgot about the live documentation – it’s an almost impossible task, we discovered, to document your own engagement whilst actively engaging. Our official photographer, meanwhile, would be able to view from the peripheries. However, I was still keen to encourage her towards indirect, tangential documentation, analogous, I suppose, to Fite-Wassilak’s text discussed earlier. In the course of pondering possible prompts for our photographer, our divergent intentions, priorities and professional obligations as artists, writers and gallery workers came to the fore as Esther Collins and Beverly Bennett said, almost in unison: ‘Community!’, ‘Debris!’

Lizzie Lloyd is a Bristol-based writer and senior lecturer in Fine Art and Art & Writing at University of the West of England.

First published in Art Monthly 459: September 2022.