Feature

We Are the Robots

Aoife Rosenmeyer asks how should we coexist with robots and intelligent machines

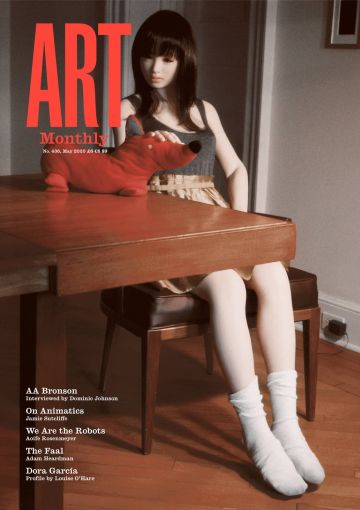

Laurie Simmons, The Love Doll / Day 32 (Blue Geisha Close-up), 2011

Aoife Rosenmeyer argues that although robots pose no threat to artists, what of the majority of workers for whom manual skills still matter? Meanwhile, children seem not to distinguish between the real and the virtual – should we be worried?

How should we coexist with robots and intelligent machines? Once avant-garde and exceptional, robots have of late been popping up regularly in highly visible art contexts. The trend raises questions about how we relate to the machines or systems that increasingly permeate our lives. By accident or design, the robotic turn marks a moment to negotiate future life.

Two mechanical, articulated arms, each on its own black, circular platform, are surrounded by thin tangles of white cord. The cord hangs in long loops from two hoops, each suspended from the ceiling above a robot, within the robotic arms’ reach. The robots should be operating but are immobile, out of order. This is how the exhibition ‘Gravitational Assertions’, a collaboration between artist Yves Netzhammer and Gramazio Kohler Research at the Graphische Sammlung of the ETH university in Zürich, appeared one afternoon in December last year.

For decades, Netzhammer has pursued a largely vector-based digital drawing practice; he investigates the potential of fluid drawing in animation and translates this into sculptural form. Netzhammer’s figures and forms morph, multiply and cross-fertilise; right now, his practice feels urgently relevant. The ETH technical university, meanwhile, boasts a renowned architectural department within which Fabio Gramazio and Matthias Kohler jointly lead the Chair of Architecture and Digital Fabrication (indeed Gramazio Kohler feature prominently in a recent Artforum article on robotic construction). An exhibition at the ETH print collection provided an opportunity for a pertinent collaboration that is perhaps better described as a two-hander from the artist and the digital fabricators. Two construction robots were taken from their laboratories to sit in a wood-panelled room in the ETH’s mid-19th-century building. For its first week the show also extended over a grand central atrium, where the Grosse Teppichbild (Large Carpet Picture) filled the floor: a single piece of white string meandering around a black carpet. Viewed best from the balconies above, the eye was led across a huge expanse. Follow the thread of this drawing and humans turn ape-like; a bird pecks the line with which it is described, the line sweeps and swoops around, with pauses for trills and arpeggios. A time-lapse video reveals how the string was placed precisely over the course of a night by Gramazio Kohler’s cobot (collaborative robot) Universal Robot UR10, a machine otherwise engaged in research into architectural fabrication at the university.

When Manifesta came to Zurich in 2016, Marguerite Humeau also availed herself of the opportunity to work with robots from the ETH, this time collaborating with the Autonomous Systems Lab within the Department of Mechanical and Process Engineering; the result was diminutive, moulded creatures about the size of automated lawn mowers which haltingly attracted and repelled each other – with hormones they emitted – through a foggy murk. Sun Yuan & Peng Yu’s Can’t Help Myself from the same year was an attention-grabbing exhibit in the Giardini central pavilion at last year’s Venice Biennale. Contained in a white box, a single arm spun and swooped, squeegeeing and corralling blood-like liquid that tried to seep away towards the edges. In 2017, Piero Golia occupied a wing of the Kunsthaus Baselland with The Painter, a single-armed robot on a track that dipped its brush in various pots to paint geometric forms on canvases taped along the wall, its movements triggered by visitors entering the space. At the Kunsthalle Basel last year, Geumhyung Jeong’s exhibition ‘Homemade RC Toy’ was staged like a workshop scenario in the midst of which the artist had assembled four-wheeled kit vehicles with human mannequin limbs. In performances, she and her vehicles came into careful, tentative concord. And Olafur Eliasson’s Kunstmuseum Zürich presentation Symbiotic seeing earlier this year concluded with a robotic arm playing a cello, the soundtrack for this immersive installation.

What is new? One might say that these examples, all but one staged within about an hour’s travel in Switzerland, follow in the footsteps of famous Swiss export Jean Tinguely; it is worth considering what differentiates, if anything, Golia’s Painter from Tinguely’s Méta-Matic drawing machines of the 1950s that manufactured artworks on demand. What is indisputably novel, however, is the broader contemporary context in which a tipping point has been reached: mechanical robots with significant autonomy can now not only replace human workers, but are economically viable and even provide a superior service. Whether mechanical robots or computing systems, machines can manipulate or fit parts more precisely and reliably, play games more successfully, trade stocks more profitably and review medical data more efficiently than their human counterparts. They can do this without the human propensity to be sick, distracted, depressed or rebellious. A robot always gives its employer satisfaction. Seen in this light, Golia embraces new-found liberty, employing a robot developed for the film industry to labour for him while he can have creative thoughts at leisure off-stage. Or, in Sun & Peng’s case, a machine can do our dirty work, safely contained behind glass. Never mind that in the work’s heavy-handed metaphor, we generated the work, dirt or blood ourselves.

Robots will take our jobs. Someone’s job, that’s for certain, particularly in countries where wages are relatively high. US market-research company Forrester published a report in 2017 headlined ‘Forrester Predicts Automation Will Displace 24.7 Million Jobs And Add 14.9 Million Jobs By 2027’. The jobs set to disappear are both in manual processes, such as manufacturing, and in digital processes, such as banking, particularly the most standardised, repetitive actions or analysis. The benefits of robots in care for the elderly or infirm is often vaunted too, and we already interact regularly with digital robot systems, sometimes unwittingly. There have been sea-changes in employment in the past, migration of work from agriculture to urban manufacturing, the reduction in employment in factories in the mid 20th century, as well as plain old depressions, but this is on a scale and with a rapidity that has never occurred before. (And Forrester’s prediction is a comparatively optimistic one.) We have grounds for concern.

The unsystematic local survey of robotics in the ‘mainstream’ art context above could be taken as an insult to the robotic art community that has operated in the electronic or the digital arts field for several decades. In this context Bill Vorn, for example, was making Hysterical Machines back in 2006, an installation of dangling, roughly spherical creatures with multiple metal limbs. Viewers who investigated them in close proximity provided the stimuli that determined how they moved. These machines were developed from a broader research project, Aesthetics of Artificial Behaviours, in which Vorn’s stated aim was ‘to induce the empathy of the viewer towards characters which are nothing more than articulated metal structures’. More recently, Vorn has been making robots dance: Copacabana Machine Sex, 2018, is a handful of figures at a human scale with limbs that approximate ours. Performing, they raise and lower arms and legs and thrust their pelvises towards the audience, a chorus line with wings drawn in LED strips. The movements are in unison, but jerky and self-consciously mechanical, not obviously softened by dampers or pneumatic joints. Vorn has spoken of machine development as a catalyst for human change, one stimulating the other. ‘It is an endless interplay’, he says, ‘of entanglement and containment between human and machine: they both take advantage of each other and progress with each other.’

Katrin Hochschuh and Adam Donovan operate as a creative duo in both robotics and arts contexts, sounding out new ground discovered as intelligent machines evolve. Building on the work of psychologists Fritz Haider and Marianne Simmel, who discovered how viewers would respond with feeling to the most rudimentary animation of triangles and squares in the 1940s, Hochschuh and Donovan’s recent project Empathy Swarm is made up of diminutive three-wheeled vehicles that cluster around or move away from viewers that interact with them based on the emotions they read on viewers’ faces. So Hochschuh and Donovan, too, are focusing on how we relate to machines and how, what is more, they might be taught to understand how we empathise, in order themselves to empathise in turn.

But before we start teaching sculptures how to feel, how do we feel about them? Even when it is immobile, I’m inclined to feel sympathy for Netzhammer’s robot collaborator. Watching the documentation of its long night drawing in rope, surrounded by technicians and overseen by the artist, I think of a prize pony performing tricks on a short rein. ‘The robot looks like it’s concentrating so hard,’ one viewer comments in the visitors’ book. Golia’s robot, in comparison, was more methodical, took its time, but pursued the task doggedly. Sun & Peng’s machine is awe-inspiringly monstrous as it brandishes its tool; surplus flourishes demonstrate its agility and provide a warning, as does its exhibition behind glass. We seem programmed to anthropomorphise and assign an emotional identity to machines if we are given the chance. (In Belfast, for example, everyone knows Harland & Wolff’s cranes as Samson and Goliath.) And we continue to do it even while – in fact, just as – machines learn how to do our jobs. At his exhibition ‘Independence’ at the Kunsthalle Bern in 2018, Tobias Kaspar employed an Aibo robotic dog; it enticed viewers with its rounded mechanical cuteness and then harvested photographs Kaspar later posted on Instagram.

Our relationship to machines that work for us is in many ways as awkward as Vorn’s robots, generating the abrasion that makes these works attractive or repulsive. ‘Robots Should Be Slaves’ argued Joanna J Bryson in 2009 in a paper arguing against assigning mechanical or digital agents any form of legal or ethical rights. ‘In humanising them [robots], we not only further dehumanise real people, but also encourage poor human decision making in the allocation of resources and responsibility.’ They work for us; they accomplish our desires. Maybe awkwardness in the face of robots is just a question of age, a steep learning curve for anyone up to Generation Z. Aleksandra Przegalinska, who researches artificial intelligence in forms such as chatbots and how humans interact with them at MIT and Kozminski University, observes a generation of AI natives accustomed to these slaves. Growing up with a ‘lady in a can’, designer Andy Polaine’s term, in the corner of the living room influences people; Pryegalinska has recorded children employing the same speech forms used when interacting with Alexa or other smart speakers when talking to their friends – abbreviated, demanding and with few niceties. Conversely, another MIT study recorded children aged 3–10 talking to such digital agents as if they were human, attributing them opinions and emotions, all while rarely considering whether they should be trusted (though three-year-old children would rarely be left in situations with interlocutors they should not trust). Before we even consider the inbuilt biases in systems such as those explored by Trevor Paglen, is it good for us to have intelligent slaves?

What about sex dolls? This is where human interaction with robots most closely resembles science fictions like those seen on film from 1927’s Metropolis to Ex Machina from 2014. Machines that unabashedly replicate a human being, with a slave’s submission, are now readily available with a starting price of about $2,000. Canadian company Robot Companion claims to have ‘combined the best features of the female mind and body to bring you a Humanoid Experience like none other on this earth’. Central heating within the robots, the company claims, ‘means not only can you enjoy their sexuality, but you can also connect with her on a human intimate level’. (Other sexes are available from other vendors.) So maybe a warm body is all we desire and we can be liberated from messy interpersonal relationships. In the ‘Love Doll’ series, 2009–11, photographer Laurie Simmons poses such Japanese sex dolls in scenes from the intimate to the quotidian, producing portraits charged with centuries of art-historical female objectification with the added frisson of a nubile and entirely submissive sexual partner. Writing in Artforum, critic Jeffrey Kastner suggests that the domestic setting ‘inoculates the scene against even the slightest whiff of perversion’; it is a questionable reading and the pictures illustrate a yawning imbalance of power. By contrast, in the 2005 publication Still Lovers Elena Dorfman records humans and sex dolls coexisting. In CJ 3, 2002, a middle-aged woman sits smoking at a garden table, a doll wearing a white T-shirt in the seat next to her. Both have blond, shoulder-length hair and they are similarly made up, and both ponder the middle distance: it might be a relationship of equals.

Being manufactured to look and feel nearly human, sex dolls are closer to the origins of robots than many of the devices we label robotic today. The term robot was coined by Czech playwright Karel Čapek in his 1920 play R.U.R., and described flesh and blood creatures that, in the work, served humans before their rebellion. In Living With Robots, philosophy academics Paul Dumouchel and Luisa Damiano highlight the importance of this origin story in how we perceive robots still: we want robots to be able to carry out human labour autonomously, but we equally want to dominate them. As a result, we continually fear an uprising from the independent beings we would enslave. In marked opposition to Bryson, Damiano and Dumouchel argue for a new ‘synthetic ethics’ and against attempts to restrict robotic development. Concentrating on the field of social robotics, robots designed for interaction with humans, they suggest, akin to Hochschuh and Donovan, that the better we understand human interaction with robots, the better robots can be developed. In an ideal outcome this, in turn, leads to a better understanding of what it is to be human. From Bryson’s position, that artificial intelligence and robotics should be clearly differentiated from personhood, to Dumouchel and Damiano’s vision of an intertwined evolution of human and robot, those of us who are not at the coal face of developing this technology may still wonder what attitude to take. Business manuals preach re-skilling, maximum flexibility, a dog-eat-dog scrabble to stay on top, and a future nirvana of more rewarding and uniquely ‘human’ employment: ‘New machines will also create work that is better, more productive, more satisfying than ever before … While some will ponder, winners will act,’ according to a recent publication ‘What to Do When Machines Do Everything’.

Back in the gallery at the ETH, on one platform I can read the outline of a Netzhammer figure drawn in string, the line looping on to other, less easily identifable forms. The other robot will soon be restarted. Its recent attempts to place more of Netzhammer’s drawings on the platform at its feet have resulted in a tangle of spiralling cord. During the exhibition, the robot’s arrangement of string in jagged patterns on the overhead hoops – described in straight lines in a technical drawing though less crisp in reality – or in Netzhammer’s more fluid designs, is, to a degree, successful. Notwithstanding a specifically designed and tooled delivery system attached to the ends of the robot arms, gravity, a gust of air or a snag in the material often intervene. The robots have been in service to Netzhammer, but even more so to their technical masters, the architects, who have been gaining pratical knowledge from the experiment. As an isolated project, this will remain experimental, without the economy of scale required for the system to be perfected. The drawings at the core of Netzhammer’s customary practice are generated digitally, mouse and program are prosthetics he commands completely; the cobot is a less wieldy tool, not yet a natural extension of his movement. Should the artist amend his behaviour to work with the robot, or vice versa?

Art is a cottage industry, a niche occupation in which scarcity and authorship continue to be prized. Manual skills, like painting or drawing, are no longer decisive for an artist’s success, so I posit that robots will remain tools for artists rather than artificial intelligence replacing human artists. (The sale of Obvious Art’s Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy, 2018, produced by a generative adversarial network and sold at Christies for more than $400,000, proved only its novelty value.) But what of the majority of employment, which does not enjoy art’s special status – and which used to promise greater job security? There is a nostalgia inherent in non-specialists like Eliasson, Netzhammer, Golia, Sun & Peng or Jeong employing advanced robots. It is a reminder of a bygone age when autonomous automation or humanity’s overthrow by machines both seemed absurdly distant, and when we could look the imagined threat in the mechanical eye. Now the most advanced designed intelligence is largely to be encountered digitally, not in robotics. These art robots are discrete entities we can regard from a distance, not the algorithms and intelligent systems with which our lives are already intertwined. The jerky, powerful, matter-of-fact or wilful gestures artists summon from robots are emblematic of how we, the still-human audience, are also currently learning, indeed being programmed to work in productive collaboration with machines. What work might be more satisfying than ever before? Are we willing to be cogs in the machine of the emerging post-industrial age? Whose machine is it? Will that truly make us winners, and what happens to those who cannot maintain robots’ pace? Might we find gratification beyond a working life, and to what extent do we want to share the privileges of identity with artificial entities? Let’s not leave it to machines to consider what being human means.

Aoife Rosenmeyer is a critic based in Zurich.

First published in Art Monthly 436: May 2020.