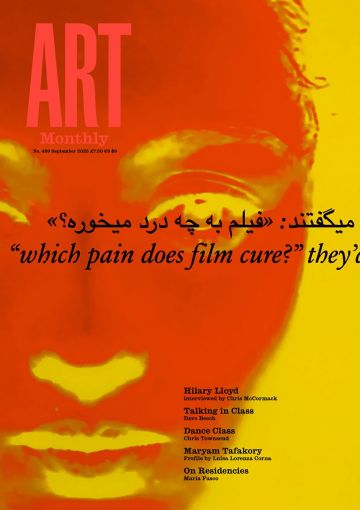

Film

Guillaume Cailleau and Ben Russell: Direct Action

Nicholas Gamso finds inherent tensions in this attempt to document radical activism

Guillaume Cailleau and Ben Russell, Direct Action, 2024

The famed Zone à défendre de notre-dame-des-landes (or ZAD), a commune of some 200 anarchists and farmers on a wetland near Nantes in Brittany, is well known for welcoming sympathetic visitors. But the group is wary of carpetbaggers (there is a fervent anti-journalist faction) and has made hostile gestures towards an exploitive and environmentally destructive art world. A manifesto, We are Nature Defending Itself, 2021, penned by two of the communards, Isabelle Fremeaux and AM contributor Jordan Jay, ridicules the sort of wasteful, peripatetic existence demanded of professional artists since at least the 1990s: ‘If your artist CV says you’ve shown in Cape Town, Dubai, Shanghai, and Prague and live between Berlin and New York, you have value,’ they write. ‘But if your bio says that you work in the village where you have lived all your life, getting to know the humans and more-than-humans who share your territory, and that your work nourishes local life, your career is fucked.’

It is a disarming statement, spoken from experience. Until 2012, Fremeaux and Jay were themselves artist-academics, living in London, shuttling from keynote to gallery talk. They joined a great migration of young-ish intellectuals escaping the city to live out radical ideas which, they say, ‘detached metropolitan beings’ only talk about. Yet whatever you think of the group’s rhetoric, or nostalgia for a moribund Europe, the ZAD is a rare activist success story worth learning from. The group defeated plans for a new international airport in the area (officially scrapped by Emmanuel Macron in 2018) and has sustained an illegal, large-scale occupation for more than a decade. To resist eviction, even to keep the place up, requires real strategy and hard work, but the reward is unmatched: life on an ancient bocage among a profusion of ‘salamanders, frogs, hawthorn, farmers, blackthorn, newts, water voles, dragon flies, deer, and orchids’.

Ben Russell and Guillaume Cailleau’s new documentary, Direct Action, is a sort of love letter to the ZAD and the rugged beauty of its human and more-than-human denizens, though ultimately it is a languishing, unrequited love, which aggravates its subjects and raises questions about how best to represent activist movements, if at all. Russell and Cailleau spent 100 days, spread over 14 months, living and working on the ZAD, but the residents forbade the duo from getting too close, refusing entry to meetings, and asking to conceal names and faces – an effort to protect so-called ‘fugitive eco-terrorists’.

Confined to the edges, the filmmakers nonetheless achieved something special: a vivid pastoral romance in the tradition of John Berger’s novel Pig Earth, the 1979 opening to his hardscrabble ‘Into Their Labours’ trilogy. The film invites us to study the seed sowing, wood chopping, and bread making which sustain the community, performed by hand and presented in wordless close-up. With the sole exception of a mesmerizing digital passage, recorded from an aerial drone, the entirety of the 3hr 40min film is shot on 16mm in rigorous vérité style (the filmmakers note the influence of Frederick Wiseman), and every second is sensorially potent, owing to the extraordinary sound engineering of Bruno Auzet. The film immerses its audience in the nature that, per the manifesto’s title, we really, truly are.

Much remains amiss, however. Never do we see the tensions or disagreements that make politics interesting (according to the filmmakers, the ZAD comprises dozens of distinct subgroups). Nor does the film acknowledge the small indignities that lend texture to daily life in even the most serene environments. Problems do come into focus at the film’s finale, when we at last glimpse the ‘action’ promised in its title: teargas filling the screen, masked protesters confronting a phalanx of French police. We witness the clash, later dubbed the Battle of Sainte-Soline, from a distant, stationary vantage, mediated by artistry that makes it feel almost staged. It is entirely real, however: scores of people are injured, some severely. In the one evident breakdown of the film’s mise en scène, a woman confronts the camera operator: ‘Is this what you should be filming?’

Discussing this moment in an interview, Russell confesses, ‘I was quite worried that I would enjoy filming the protest – and I felt very glad that I didn’t like it at all’. Elsewhere, the directors explain the seeming generalities of the film – a means of ‘diffusing the idea of the individual’ – and defend the digital drone shot as an allusion to peasant militancy. There are other provisos: the film is not ‘utopian’, the activists aren’t ‘hippies’.

Presumably the directors’ remarks are meant to reassure us of the directors’ political seriousness. But one also senses certain insecurities, perhaps stemming from success (the film competed at the Berlinale and New York Film Festival), and resonant with irresolvable debates over authority and exploitation in documentary more generally. The strange effect is to undermine what is most salient in this fascinating, if imperfect work: a yearning for a world that doesn’t want to be seen.

Nicholas Gamso teaches in the history of art and visual culture programme at California College of the Arts.

First published in Art Monthly 489: September 2025.