Review

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories

Larne Abse Gogarty discovers a pointed layering of references in the American painter’s retrospective

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Blanket Couple), 2014

In 2017, I saw Kerry James Marshall’s first US retrospective, ‘Mastry’, at the MOCA Geffen in Los Angeles, a summary of the artist’s then 25-year career. In contrast to the bright airy rooms of the MOCA, all white walls and light wooden floors, which look so much like any ‘modern’ art gallery, the presentation of Marshall’s work at the Royal Academy is an entirely different experience. To begin with, the walls are painted in colours ranging from shades of deep red and sage green to midnight blue – clearly ‘The Histories’ does not shy away from the conventional trappings of display methods at the RA, with its cloistered heaviness and gilt edges. On the contrary, history bears heavily on Marshall’s work, and its presence takes on new dimensions in an institution that formed a crucible within the development of British art and art history, with all its elitist, racist and misogynistic trappings. Following the conventions of the French Academy, history painting was considered the highest genre for painting in the RA, forming part of the entrance exam from its founding in 1768 and remaining central to its curriculum and hierarchies of taste until the 20th century. From the outset, art history was concerned with defining how it expresses national identity – read, racial style – and, as Éric Michaud suggests, the discipline has long conceived of art as a ‘sort of bodily secretion of the nation as a whole’. In response to this, Marshall’s project as an artist is often understood primarily through a politics of representation that reinvents the Western canon with black subjects and perspectives at the centre. Because of this, he is often thought of as a history painter, not only because of his subject matter – portraying historical figures, including Harriet Tubman, Nat Turner and Olaudah Equiano – but also because of his use of formal conventions in his large-scale scenes, which are riven with a narrative drive filled with detail and iconography. Yet his importance to the development of painting since the 1980s is larger than this: he distils and reinvents pretty much the entire history of painting within the Western canon and beyond, both in terms of representation but also for how that project becomes inextricable from artistic invention at the level of form.

Through these rooms we have a treasure trove of easter eggs nestled within the canvases: Hans Holbein’s anamorphic skull from The Ambassadors, 1533, is reimagined as Disney’s Sleeping Beauty in School of Beauty, School of Culture, 2012, and at the back of that painting we also find reference to Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, 1656, the painter’s appearance in a mirror transmuted into a selfie and camera flash. Sandro Botticelli’s iconic depiction of Venus from his Birth of Venus, c1485, appears on a gun in Abduction of Olaudah and His Sister, 2023, and the frippery of 18th-century rococo reappears, appropriately, mingled with Hallmark-style glitter in his 2003-07 ‘Vignettes’ series. When Marshall’s engagement with art history is submerged at the level of structure rather than flushed to the foreground through iconography, it often becomes a means to make decisions about the arrangement of figures as in the riff on Edouard Manet’s barmaid in Untitled (Club Scene), 2013. This wide-ranging approach to the history of painting is underpinned by Marshall’s total emphasis on invention, or, as he put it when I interviewed him in 2017: ‘Look at everything, figure out how it works, and know it from the inside out. Then try to do what you think you need to do.’ His work is emphatically cognitive, emphasising the practice of making and looking as intellectual processes. What this means is that you could look at any one of the works in the show, ideally with other people, and talk about it for an hour or more, which goes against Marshall’s own statement that ‘nobody really goes to art museums to learn how they should live’. Of course, the potential of an exhibition at the Royal Academy will always have pedagogical limits in such world-shaping ambitions, but ‘The Histories’ offers rich possibilities for thought which readily cross over from the canvas into the world and back again.

Dwelling on the details, I am continually seduced by his smudgy flowers and, more generally, by the ways he handles layering, which is most captivating in his ‘Garden Projects’ series, 1994-95, and again, in totally different ways, in his Black Painting, 2003-06. In Watts 1963, 1995, the graphic, low-rise housing block that Marshall’s family lived in for two years is topped by a folded banner that appears to read triumphantly: ‘more of everything’. Here, his pale pink flowers seem like the chopped heads of Manet’s roses, encircled with Cy Twombly-like scrawls and filtered through the dusky pinks found in Marshall’s production design for Julie Dash’s 1991 film Daughters of the Dust. In the lower right passage of the unstretched canvas, a girl walks in pink flip flops, her purplish-black ovoid shadow stretching out in front, while the two boys next to her respectively kneel and curl down on their own shadows. The picture deals in utopian abundance, the idea of the ‘Garden Project’ promise, as another in the series suggests: Better Homes, Better Gardens, 1994. Many such housing projects were products of President Lyndon B Johnson’s so-called ‘War on Poverty’ reforms that, before long, revealed their Janus face domestically in the form of the ‘War on Crime’ and the expansion of the US carceral state, so that areas like Watts became, in Johnson’s words, a ‘war within our own boundaries’ to match the wars being conducted overseas, in particular in Vietnam. In the ‘Garden Projects’ paintings, the half-undone passages strike me as speaking to this: imagining what can be done with these histories, how the utopian possibilities could be seized – as Saidiya Hartman has emphasised – as spaces that provided slivers of freedom as ‘wild experiment, a prospect that vibrates through Marshall’s handling of those scenes.

Correlating with his emphasis on construction, which often means toggling between abstract passages, symbolic detail and the arrangement of figures in a particular setting (the barbershop, the bedroom of the slave master or the studio, for example), Marshall frequently emphasises his lack of interest in chance and the irrational, that central strategy of so many avant gardes. But we should not take this as signalling some sort of hard-headed investment in rationality, or a replaying of the enlightenment values that underpinned the hierarchies of genre and people that were formed within the halls of the RA. His emphasis on relationships gets in the way of that, both in the strikingly intimate moments, such as Blanket Couple, 2014, as well as the tenderness extended towards childhood, as expressed for example in the scene and titling of Knowledge and Wonder, 1995. This is also evident in the later rooms of this show, where the devastation and acquisitiveness depicted in The Abduction of Olaudah and his sister, 2023, and Untitled (Policeman), 2015, are marked by an engagement with the forms of intramural violence between black people that are part of the history of slavery, colonisation and capitalism. Horror, in Marshall’s work, is never naturalised into some amorphous notion of human nature; instead, it is situated historically as springing from choices that were made which can be learned from.

There are some works I wish were in this show, such as the precise and stark Heirlooms and Accessories, 2002, which extracts the faces of three women from a photograph of a lynching and places them into lockets. The title signals white supremacy as an heirloom, an inheritance, tasking us with the urgent need to consider how the family, state and capitalism reproduce racism.

The lack of strictly abstract pictures is also surprising, and I would have liked to have seen Red (If They Come in the Morning), 2011, once again for the way Barnett Newman collides with Angela Davis and the history of Pan-Africanism in just a few, elegant moves. It is perhaps doubly surprising given curator Mark Godfrey’s scholarship in the field, but, as he writes in the catalogue, part of what Marshall did for him was throw his modernist training into disarray, transforming his attitude on the possibilities of representational painting after abstraction. This show helps us reappraise such questions after the converse has happened: a widespread boom in representational painting and arguably a displacement of abstraction from the centre of attention. More than that, it emphasises the possibilities of art as a vehicle for learning, and the ways in which making as invention can exist less as a myth of individual specialisation and more as a model for curiosity and a commitment to shared study.

Larne Abse Gogarty is a writer and associate professor at the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL.

‘Kerry James Marshall: The Histories’, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 20 September 2025 to 18 January 2026

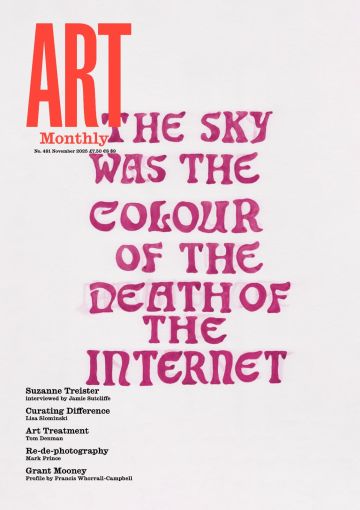

First published in Art Monthly 491: November 2025.