Feature

Photography as Work

Stephanie Schwartz questions the utopian potential of digital photography

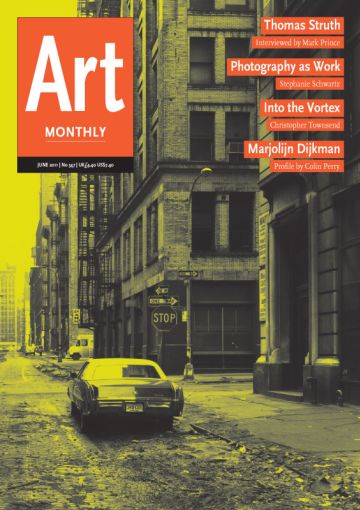

Allan Sekula and Noël Burch, The Forgotten Space, 2010

The recent wave of protests in the Middle East has markedly reinvigorated long-held debates about photography’s utopian promise. Across the mainstream press and on a slew of new websites dedicated to citizen journalism, amateur photography is once again being championed as a weapon of revolution. Cheap, malleable and automatic, photography in the digital age has spawned a new cadre of citizens ready – and eager – to erode the separation between production and consumption. By taking photographs on mobile phones and uploading them to user-generated content (UGC) platforms like Facebook, Flickr and WeMedia, ordinary citizens are now able to create and spread the news. Or, more to the point, what is left out of it. As the promoters of the ‘Street Journalism’ online newswire Demotix suggest, ‘News by You’ has finally trumped ‘All the News That’s Fit to Print’.

Some among us are suspicious of the indymedia revolution. Do celebratory declarations about the new demos, the concept from which Demotix takes its name, ring hollow when we consider that more than half of the world’s population has never used a mobile phone or logged onto a website? The issue of access to technology aside, has the emergence and subsequent fetishisation of digital photography effaced the very claims of realism upon which the promise of the photograph’s revolutionary potential was based? It is the latter question that hangs over ‘A Hard, Merciless Light: The Worker-Photography Movement, 1926-1939’ now on view at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid. Curated by Jorge Ribalta, the exhibition, which brings together an amazing array of documents (photography, film, posters, books and illustrated magazines) from a period when reporting was inimically tied to the index, asks us to measure the euphoria of the digital revolution against the lessons of the analogue age. In a recent interview for Foto8, Ribalta insisted that the current debate ‘tends to naturalise an anti-realist discourse concerning photography’, adding: ‘Its effect is to erase the documentary power of photography, which is precisely the political potential to link art to transformative radical politics.’ In other words, are ‘we, the people’ even less prepared today to stage a revolution? In ‘Universal Archive: The Condition of the Document and the Modern Photographic Utopia’, an exhibition tracing a history of photography from the medium’s invention through its reformulation in the 1970s and again today, which he curated for the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona in 2008, he similarly asked: has the spectralisation of digital photography trivialised the document?

Raising these concerns in the museum is no easy task, and not simply because the organisation of an exhibition dedicated to reintroducing class-consciousness into our histories of Modernism might not necessarily draw visitors. The promise of digital photography has not only transformed the way in which ‘we’ navigate image culture, it has fundamentally altered our institutional histories of photography. If photography matters more today than ever before, to borrow Michael Fried’s refrain, it matters as art. In the digital era photography may provide the possibility for the amateur to have a say, but it has also been used to overturn the museum’s long-held suspicions about photography’s mechanicity. Exhibiting large-scale, often singular and expensive photographs by such celebrated photographers as Thomas Struth, Jeff Wall and Thomas Demand, the museum, as Julian Stallabrass recently argued in ‘Museum Photography and Museum Prose’, has conveniently reskilled and redefined photography as a plastic art. Contrary to popular perceptions, it seems that the professional photographer has surely not lost any ground. It is this binary opposition between the amateur and the professional that ‘A Hard, Merciless Light’ seeks to historicise, and it does so by reminding us that amateur photography was born out of, not created in opposition to, the rise of a conservative, mediated public sphere.

The exhibition begins by focusing on the media with the call, published in AIZ (Arbeiter-Illustraiter Zeitung/The Workers Illustrated Paper), for workers among its readership to send in documents of the working-class struggle. These include the now iconic photographs of men at work, waiting in soup lines and sleeping on park benches, as well as the movement’s training grounds. For example, the exhibition encapsulates the Comintern’s desire to tap into the media’s promise as a two-way street with a selection from Eugen Heilig’s ‘The Cinema Comes to the Village’, the German photojournalist’s 1927 series of portraits of Soviet workers mesmerised by image production in the industrial age. The exhibition follows this media frenzy through the movement’s spread beyond Germany and the Soviet Union into metropolitan capitals including Prague, London, Vienna, Paris, New York and Mexico City in the early 1930s, carefully documenting in an audio-visual display of moving and still images the emergence of the proletariat public sphere. Ribalta caps off what can only be described as a feat of archival research with the five-part film series ‘Poetics of Dispossession: Proletarian Documentary’, which includes works by Dziga Vertov, Joris Ivens and the rarely screened newsreels of the US Workers’ Film and Photo League. And seeking not to leave us in the past but once again to connect the exhibition to present-day documentary work, Ribalta invited Allan Sekula to screen The Forgotten Space, 2011, the sequel to his 1995 photoseries ‘Fish Story’, in which Sekula arranged archival footage, still photography and interviews to document the mediation of labour in the global sea-based economy.

The exhibition takes its title from German pedagogue Edwin Hoernle’s 1930 article ‘The Working Man’s Eye’. Published in Der Arbeiter-Fotograf (The WorkerPhotographer), the monthly journal of the Association of the German Worker-Photographers, Hoernle characterises the project of worker photography as follows: ‘We will have no veils, no retouching, no aestheticism; we must present things as they are, in a hard, merciless light.’ Framing the programme through the aestheticism of bourgeois media, Hoernle’s text pointedly encapsulates the core of the movement’s drive. The worker-photography movement called for much more than documents of working-class struggle (portraits of toiling workers, industrial machines and mass demonstrations); it sought to produce a perceptual revolution commensurate with the industrial times, ie with capitalism itself. As Vitalii Zhemchuzni explained in his 1926 article ‘Attention Photo Amateurism!’ for the mouthpiece of Soviet photojournalism Sovetskoe foto (Soviet Photo): ‘The pursuit of photography organises the visual perception of the surrounding reality. The recording of the distribution of light and shadow, the arrangement of people and things in the visual field of the lens, the selection of viewpoints for shooting – all of this nurtures an aptitude for “visual orientation”.’ Proletarian documentary work, ‘A Hard, Merciless Light’ instructs us, is itself labour. Contrary to the colloquial definition of the document as the objective and authentic treatment of reality, the Comintern’s international media conglomerate proposed a reshaping of perception in accordance with the volatility of production. In turn, as Hoernle concludes, proletarian documents must be stripped of humanism and the bourgeois spirit of compassion.

‘A Hard, Merciless Light’ simultaneously documents and reanimates this perceptual revolution. In addition to hanging the photographs produced by workers who toiled on the industrial frontline, the exhibition displays the newspapers, films and photomontages in which this ‘hard light’ circulated and was reproduced. This juxtaposition matters. It puts the photographs to work. The standard museum display of photographs as singular images and pictures is compromised by the cropping, cutting and semiotic play between text and image that takes place on the pages of the press. The lesson of the analogue era is not only that we must now work differently; it is that political work is never about gathering the truth. Like reality, the document is contingent, and spreading the news is a task that requires an editor or a master of propaganda. As the founder of AIZ Willi Münzenberg noted in one of the many articles from the proletarian publications on display in the exhibition (and reprinted in the exhibition catalogue The Worker-Photography Movement [1926-1939]: Essays and Documents), a skilful editor can reverse the significance of a photograph and influence the reader ‘in any direction he chooses’. In short, ‘A Hard, Merciless Light’ reinserts proletarian photography into the history of Modernism not by pointing out its difference, but by demonstrating the dialectical relation between capitalist and communist spheres of productions.

Given Ribalta’s commitment to foregrounding the document’s contingency and the movement’s ‘hard light’, the exhibition closes with a somewhat surprising display of texts and images. Organised under the subheading ‘Documentary Poetics’, its final section showcases the documentary strategies of the Popular Front, when the left repurposed the class-based propaganda campaign against capitalism as an international struggle against fascism. The wall text frames that movement’s first years nostalgically by categorising the Popular Front as the ‘last episode in the iconography of the proletariat’. It is not only the rhetoric of the exhibition that has shifted from the project of a perceptual revolution to its organisation as image: so has that of the photographers. This last episode is documented by the work of Robert Capa, David Seymour and Henri Cartier-Bresson. The trio, who were responsible for founding Magnum Photography in 1947, were not worker photographers and the photographs on display, including Cartier-Bresson’s now iconic Children Playing in the Ruins, Seville, 1933, surely have compassion. All of a sudden, at the exhibition’s final turn, we have authors and singular images. Sevilla is a textbook example of Cartier-Bresson’s theory of the ‘decisive moment’, in which, as he explained, ‘Photography is simultaneously and instantaneously the recognition of a fact and the rigorous organisation of visually perceived forms that express and signify that fact.’ The document is no longer active. The act of photography is now couched in the past tense.

Perhaps we can cut Ribalta some slack for diluting the work of the movement with photographs eventually bound for the pages of Life magazine and Edward Steichen’s 1955 blockbuster exhibition of compassionate photographs ‘The Family of Man’. Given the exhibition’s venue, it is no surprise that Ribalta would want to close ‘A Hard, Merciless Light’ in Spain and with the Spanish Civil War. Yet, we could also see this shift from amateur to professional, or from the mechanics of visual reorientation to iconography, in a ‘merciless light’. To end an exhibition which champions the working-class eye with the production of working-class iconography is not nostalgic, nor is it wholly misplaced. It puts the onus on the viewer to historicise the very crisis of realism and the potential for the document today.

The Web 2.0 revolution, despite suggestions otherwise, does not reinvigorate the utopian promise of the worker movement. It reinvigorates the emergence of the ethics of photography in the mid-to-late 1930s with what media historian Mark Deuze, in his article ‘The Future of Citizen’s Journalism’, has classified as a ‘new humanism’. Noting that much of what is now posted on websites like Demotix and WeMedia is deeply personal, Deuze reminds us that we now find ourselves in a highly individuated, rather than communal, public sphere. The news may be ‘by you’ and aired without a corporate media ban, but it also clings to the supposed connection between immediacy and transparency. Qualifying his bitter pill, Deuze adds, if humanism functions as antidote to corporate media, ‘it is also the inevitable side effect of current corporate practice’.

The side effect in which news becomes personalised in terms of individual experiences and human interest stories – the CNN effect – has little to do with the utopian promise of the analogue era, when the difference between reality and fiction or amateur and professional did not really matter. Rather, what ‘A Hard, Merciless Light’ demonstrates is that the digital revolution more often than not transforms the work of the document into work on behalf of the media. Taking and uploading photographs on UGC platforms is a form of free speech; it also provides mainstream media platforms with cheap labour and marketing opportunities. The so-called indymedia revolution, in other words, is perhaps only a revolution in name: it seeks to democratise capitalism, not overturn it. Cast in a hard light, the lesson of the analogue age – and the workers-photography movement – is that simply knowing or having access to technology does not change anything.

‘A Hard, Merciless Light: The Workers-Photography Movement’ was on view at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid from 6 April to 22 August 2011.

Stephanie Schwartz is a lecturer at University College London.

First published in Art Monthly 347: June 2011.