Performance

Saidiya Hartman: Minor Music at the End of the World

Vaishna Surjid on a doomsday performance that nevertheless suggests ways forward

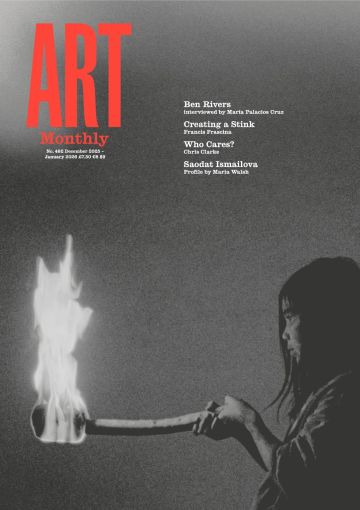

Saidiya Hartman, Minor Music at the End of the World, 2025

It has always felt hard to pin down Saidiya Hartman. The American academic has long defied genres, troubling archives with her own, much celebrated method of critical fabulation. In her ambitious multimedia performance work commissioned by the Hartwig Art Foundation, Minor Music at the End of the World, 2025, Hartman asks what the end of this world will look like. This is also the first time that Hartman’s writing has been adapted for the stage. Directed by Sarah Benson, the performance was produced in collaboration with renowned artists and actors Arthur Jafa, Precious Okoyomon, Cameron Rowland, André Holland and Okwui Okpokwasili, and combines theatre, film, installation art, movement and sound to tease open the limits of each form and create what Hartman calls a ‘performed discourse or choral utterance’.

The first movement is based on Hartman’s essay ‘The End of White Supremacy’, 2015, a text that also incorporates W.E.B. Du Bois’s speculative tale The Comet from 1920, in which a comet hits New York, the only survivors being a black man, who was inside the vaulted underground safe of a bank, and a white woman.

Prior to entering the theatre, audience members were handed a copy of Cameron Roland’s essay ‘De Kluis’ (The Safe). His essay explores the origins of Dutch banking in global economies of slavery and connects this history to modern America and racial capitalism. This short but powerful text attests to why a performance in English, set in New York, and written by an American premiered in Amsterdam.

The performance begins just before the comet destroys the city and shows Holland (playing the last surviving man) in the basement of a bank projected across nine channels of black-and-white, surveillance-like footage. As the image slips in and out of focus we watch the actor from different angles: from behind and in front, he is in the distance and then seemingly absent; he is at once hyper visible and evasive. It also reads as a nod to Du Bois’s seminal notion of double consciousness, which he described in the 1903 essay ‘The Souls of Black Folks’ as a ‘sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity’.

Eventually Holland emerges from the cavernous basement onto a barren stage of a now decimated New York. On a large backdrop screen a short selection of clips from various sci-fi, racial dramas and doomsday films plays behind the performer; occasionally, a further powerful doubling takes place as Holland’s gestures mirror those projected, a mimicry that asks us to draw together Du Bois’s thinking from 1920; a century of sci-fi films; Hartman’s thinking in 2015; and our fractured present day. These connections are a reminder of the enduring fascination artists have with picturing the end of the world, seeing it as way to speak to the present while holding out imaginative possibilities for the future.

The second movement is a departure from the opening audio-visual staging and begins with a large black crinkled tarpaulin glimmering under spotlights as it unfolds and slithers across the stage. It transforms from a writhing sea, animated from beneath by Okpokwasili and three other performers, to a mountaintop around Okpokwasili’s waist before forming rubble as the figures eventually become free of it. Early in the second movement, Okpokwasili wails a guttural lament, despair rippling through her body as she embodies both exhaustion and endurance. In her short essay ‘Litany for Grieving Sisters’, Hartman writes: ‘She is not a mother, and yet she has mothered … Care will swallow her whole, steal her last breath, crush and destroy her.’ Eventually, the performers collectively disappeared into a haunting tree installation by artist Precious Okoyomon: a portal to a new world.

The final movement was a remix of Arthur Jafa’s digitally produced film Aghdra, 2021. The film at times appeared as a deep expanse of black water reverberating, at other times as if charred rocks or lava bubbling under tectonic plates. The film feels both primordial and futuristic, signaling the rebirth that occurs at both beginning and end. Is this what nothing looks like?

Saidiya Hartman’s writing is revered. On stage it has been granted a different power, transformed into a new affective experience. Okpokwasili’s cries and Holland’s humour reverberated through the crowd, leaving the audience singed and recast. The performance offered new ways to reimagine ‘world’ as a concept. Perhaps through this interdisciplinary collaboration, it’s clear that this is work that we must do together.

Saidiya Hartman’s Minor Music at the End of the World was performed at Internationaal Theater Amsterdam, 3-4 October 2025.

Vaishna Surjid is a writer and curator based in Manchester.

First published in Art Monthly 492: Dec-Jan 25-26.