Feature

Empire, Extinction and Ecstasy

Izabella Scott claims the US is obsessed yet in denial about the concept of empire

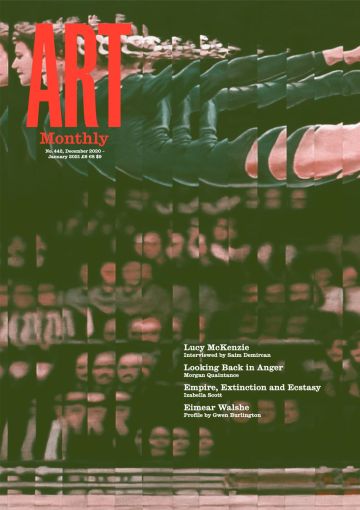

Danh Vō, Untitled, 2020

The US has long been both in denial and in thrall to the concept of empire. Izabella Scott looks at US colonial history through the lens of artists such as the Vietnamese-Danish Danh Vō, who lives and works in Germany and Mexico, and the writings of Chinese-American author Ling Ma.

Chicxulub is the name of an impact crater, more than a hundred miles wide, formed when a city-sized asteroid hit the earth around 66 million years ago. The asteroid hit what is today the seabed just off the northern shore of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Its collision triggered earthquakes, eruptions, firestorms and a ring of tsunami waves a hundred miles high. The sky darkened; clouds of debris prevented photosynthesis for decades. Life on earth stuttered and then expired. Half the world’s species became extinct.

Ever since the crater was discovered by geophysicists in the 1970s, and especially during the internet era, Chicxulub has captured the imagination and become quasi-mythic. Invisible to the naked eye, the crater provided an irresistible opportunity for conjecture, attracting a rush of theories from the scientific world and popular culture alike – a fever nothing short of an extinction fetish. One scenario lodged itself in the public mind more than any other, that Chicxulub explains the dinosaur mass extinction. In this version of events, the largest, most spectacular creatures to have roamed the earth were wiped out in a single afternoon.

‘Chicxulub’ is also the title of Danh Vō’s recent exhibition at White Cube in Bermondsey, south London. As in past work (Interview AM372), Vō remains preoccupied by US imperialism and the history of Vietnam (his country of origin), but here his focus was intensified. ‘Chicxulub’ staged the death of the US, as Vō joined a lineage of artists and writers who have imagined America’s destruction, depicting a nation that has gone, as WEB Du Bois once warned in the late 1930s, ‘the way of the Roman Empire’.

To visitors, the gallery appeared as a bunker, dotted with stoves and crates holding sacred fragments, such as a worm-eaten torso of Christ and a splintered Madonna and Child. Whoever congregated here – be it displaced Americans or their Barbarians – had made efforts to rescue and cultivate plant life. In one room, beds of weeds and ferns grew under buzzing artificial lights. In another, a dying apple tree had been propped up by wooden stilts. There was also a giant image of the US flag, which was incrementally destroyed over the exhibition’s run. The flag took over an entire wall of the gallery, was 10m wide and built from a pile of logs, which had been alternately stacked to evoke the stripes in bark and sapwood. Meanwhile, 13 metal stars had been inserted into the stack. The show’s running dates provided clues to the particulars of Rome’s fall, opening on the anniversary of 9/11 and closing on 2 November, US election night. Every day the exhibition was open, logs were removed to burn in the stoves, and the flag shrunk. As Americans headed to the polls, the silver stars were left as ruins, rolling to the floor.

Flag desecration has a long, inflammatory history in the US, most poignantly as a feature of protests against the Vietnam War. At the same time, US artists like Jasper Johns have depicted the flag – rendered 40 times across his career – in apparent critiques of imperialism, made complex by their immense popularity. In these works, Johns’s iconoclasm bleeds together with the pleasure so many US citizens take in looking at the flag in all its glory – a stain of narcissism that renders the work’s politics ambivalent. Constructed in Europe, Vō’s shrinking and eventually incinerated flag symbolised a diminishing respect for the US – the show’s dinosaur – which has now reached home. Since the end of the Second World War, the US has indulged a myth of being the global peacekeeper, purveyor of liberal democracy, but that myth was rarely convincing to anyone other than its own citizens. During this period, capitalism was exported by the US around the world, apparently in the name of progress, profit and peace, using the age-old method of warfare. Indeed, between 1945 and 2020, the US took part in 211 military engagements in 67 countries (according to historian Daniel Immerwahr’s book How to Hide an Empire). For those on the receiving end of US aggression, like Vō, whose family was forced to lee South Vietnam in 1979 on a homemade boat during the Vietnam War, the US was always a warmonger, using its power to promote the rule of wealth, not peace.

By staging the US’s Chicxulub moment, Vō suggests that an era of American exceptionalism is over. It’s unclear where this fictional bunker was meant to be located – in the ruins of Washington DC or somewhere far away from the centre. Inside, the relics of an obliterated US included religious ephemera combined with consumer packaging. In Untitled, 2020, a 15th-century bust of Christ was slotted inside a Carnation Milk crate. In other works with the same non-title, a church window showing the biblical Magi cast light on a gilded Coca-Cola carrier, embossed with holly for the Christmas season. Here, Vō’s established method of splicing together objects from different orders and eras – seen across his practice – is deployed to compare religion and capitalism, both of which are shown to have colonialist and imperialist intentions.

The sculptures dotted around the bunker also reflected on Vietnamese history, the region having suffered several waves of invasion, first by French Catholic missionaries and later by US commercial assault (when plain old colonisation was replaced by Coca-Colanisation, as the French communist party named it). Vō was four years old when his family was rescued at sea by a Danish tanker and taken to a refugee camp in Singapore. Hung on the bunker wall was a photograph, taken on Christmas Day 1979, showing a young Vō and his siblings at the camp. With this gesture, Vō locates his Chicxulub event in the past as well as the future, suggesting that it is not a single, cataclysmic episode, but rather one that is semi-permanent and repeated over and over again.

If Vō’s bunker is for Chicxulub survivors, it’s for those who have turned against the empire and come to watch the flag burn, a necessary hideout for those on the receiving end of US aggression. Some of that violence, like the Vietnam War, is well documented; other forms of coercion have taken place out of sight, in what Immerwahr calls America’s ‘hidden empire’.

The story of this camouflaged empire begins in the 19th century, when the US claimed over a hundred uninhabited islands in the Caribbean and Pacific. Next came the 1898 Spanish-American War, when Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines came under US rule – a victory marking the emergence of the US onto the global stage. Imperialist acquisitions continued across the century’s turn – Hawai’i, Panama, Samoa, the US Virgin Islands – a collection of pinpricks and territories which became known as ‘the Greater United States’.

Even so, from the beginning, US politicians have always had an aversion to using the ‘c-word’, as Immerwahr calls it, and ‘colony’ was shunned in favour of the gentler-sounding ‘territory’, which didn’t undermine the US’s vision of itself as modern, democratic, libertarian and, most importantly, moral. By 1945, the US administered a vast and sprawling collection of strategically located atolls and archipelagos, ‘a pointillist empire’ that, as Immerwahr explains, refused to register in the US popular consciousness.

In recent years, with the ascendancy of Donald Trump, the US has come to suffer a kind of identity crisis. Human rights’ abuses, a corrupt administration and white nationalism are no longer ‘hidden’ from its citizens. By locating Chicxulub in the US, Vō reflects on this psychological crisis, whereby America’s sins – old and new – are dancing into view, a set of facts about the nation that are not so much ‘new’ as ‘newly exposed’. If the empire’s antics are difficult to make out from the mainland, however, they are impossible to miss from the zones of colonial rule, and Vō’s show was also a reminder that the myth of American exceptionalism was only ever convincing to – mostly white – Americans.

Visions of the end of America are far from new; in fact, they abound in what amounts to a Hollywood obsession. The industry has staged the end of the world – which usually means the end of New York – again and again. A genre of films in which the Manhattan skyline is crushed predate 9/11. The elaborate Chrysler Building is a popular choice for on-screen obliteration, sometimes by a giant meteorite, as in Armageddon, 1998, or else by the US military itself, as in Godzilla, 1998. Other films that stage the sacking of New York span the postwar era and include Planet of the Apes, 1968, Meteor, 1979, Escape From New York, 1981, Independence Day, 1996, Deep Impact, 1998, The Day After Tomorrow, 2004, and I Am Legend, 2007, to name a few. A recent, electrifying incarnation of New York’s demise is found in a 2018 novel by the Chinese-American writer Ling Ma, Severance. It tells the story of a fictional pandemic emerging from China and travelling around the globe via consumer goods. Shen Fever, as the infection is named, is transmitted by fungal spores picked up in factories and inhaled by consumers. One of the dangers of Shen Fever is that it is difficult to detect – early symptoms appear no different from a common cold. After a three-week incubation period, symptoms worsen: headaches lead to memory lapses until the sick begin to blankly repeat familiar tasks. Eventually they become low-functioning zombies, who keep going to work and performing admin tasks. As well as an incurable sickness, Shen Fever also functions as a metaphor for the gothic exploitation at the core of capitalism (networks of oppression that are, like the US empire, so often hidden). For months, across the summer of 2011, nobody in New York takes the fever seriously. It is considered a fringe outbreak and largely ignored, in part due to suppressed reports coming out of China, and also as a result of the ruthlessness of free-market business-as-usual economics, regardless of human cost. Employees, who barely make their inflated Brooklyn rents, can’t afford to stop working. The companies they serve won’t pause production.

Ma’s protagonist is a millennial named Candace Chen, who works at a publishing corporation, Spectra, which manufactures wares in China. As the novel opens, she is producing a Bible marketed at pre-teen girls, which comes with a gemstone keepsake freebie. That necklace is made in such dire conditions that workers in Guangdong, the gemstone region of China, are dying of lung disease. However, it is not Bibles that Spectra is producing, at heart, but capital. ‘The most Gothic description of Capital is the most accurate,’ wrote Mark Fisher in Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Reviews AM333), as if describing Ma’s conceit. ‘Capital is an abstract parasite, an insatiable vampire and zombie-maker.’

Malls feature across the novel – sanctuaries before and after New York’s Chicxulub, where citizens shop to forget the pandemic and where survivors take refuge. (In this way, the malls echo Vō’s bunker, with its rooms stocked with branded artefacts: alongside the Carnation Milk and Coca-Cola packaging were crates imprinted with the Johnny Walker logo, Gloria Lait and Beefeater Dry Gin.) Malls are also where the fevered go, continuing to mindlessly stack shelves and sift through rails. This is how the fever plays out in a society addicted to consumption – itself a kind of fever. Naturally, fashion masks in black or leopard print, or with the Supreme logo, abound. Ever benevolent, Spectra provides employees with a personal-care kit – flimsy cardboard boxes holding respiratory masks, latex gloves and an expanded insurance plan – but workers continue to get sick. By the time the government starts to panic, implementing a ban on Chinese imports, it’s far too late. Shen Fever is everywhere, and the apocalypse unfolds.

Two years ago, when Severance was published, Ma’s premise was implausible. If anything, her Shen Fever scenario was an outlier vision – operating best as black humour, as social critique – and the novel was classed as an office satire. Nobody is laughing now. As we live through what she imagined, today Severance can only be read with a mixture of fear, excitement and awe. Was the pandemic really so predictable? Clearly it was foreseeable from an Asian worldview. Now located in the US, Ma herself was born in Fujian, the province in China where the bird flu epidemic of 2003 emerged. And Ma was not alone in her vision of an apocalyptic sickness originating in China: Larissa Lai’s science-fiction novel The Tiger Flu, published the same year as Severance, follows a mysterious animal flu as it ravages an Asianised Canada of the future.

Ma takes an intense pleasure in writing New York’s death, a city she dismantles across the novel, just as Vō destroys the flag. Candace documents the fall; inexplicably immune from the fever, she remains at her desk even as the apocalypse unfolds. During her lunch breaks, she gazes down on Time Square. At first, tourists arrive, taking advantage of drastically reduced airfares, but soon they disappear, along with the city’s entire populace. When her work dries up, Candace begins to wander a deserted city, publishing photographs of what she sees on her blog, NY Ghost, snapping the entrances to flooded subways where candy bars and corpses swirl together; the ghetto-palms already sprouting from the pavements; the smashed boutique windows, spilling terry-cloth and velour; the ominous security guards and shrines.

That New York exists as an image, a fantasy, as much as a physical location means that in order for it to be destroyed its destruction needs to be captured and circulated, and occur on the level of the image. Candace knows this implicitly; visitors to her blog click on, enraptured. ‘It was as if they still couldn’t believe New York was breaking down, and needed confirmation,’ Candace reports. ‘Everywhere else could fall apart, but not New York. Its glossy, reflective surfaces and moneyed environments seemed invincible.’

Ma captures the cycles of empire as Candace gazes down on the city, like the last emperor. ‘Looking out the windows, I imagined the future as a time-lapse video, spanning the years it takes for Time Square to be overrun by ghetto palms, wetland vegetation, and wildlife,’ Candace ruminates. ‘Or maybe I was actually conjuring up the past, the pine- and hickory-forested island that the Dutch first glimpsed upon arriving, populated with black bears and wolves, foxes and weasels, bobcats and mountain lions, ducks and geese in every stream.’ This vantage on history echoes a text that accompanied Vō’s show, a timeline stretching from 330BC to 1945 (accessible via a QR code), which listed the sacking of Ancient Macedonia, the fall of Rome, the collapse of the Qing Dynasty and the bombing of Japan – a litany of 22 Chicxulubs, where the mighty fall.

Thomas Cole’s saccharine and once-beloved series of paintings ‘The Course of Empire’, 1833–36, is a case in point. Over five canvases, Cole charts the rise and fall of a great city, which, like Ma’s Manhattan, rises from the pastures and returns to dust. The third and central painting, The Consummation of Empire, conjures a scene of urban decadence, a great metropolis replete with elephants, glittering columns, festive crowds and slaves, which has grown out of the swamp. But the capital is soon ravaged by wars and storms until little of it remains; the final scene, Desolation, is an echo of the first: a pastoral landscape of yore, only this time littered with ruins. Cole’s Romantic rapture over the empire’s fall, where Manhattan is allegorised as Rome, advances a cautionary and popular tale in which imperial greed is punished. Yet, ironically, rather than inspiring anti-colonial sentiments, as Cole hoped, these paintings also fed the colonial imagination.

More than 150 years later, Ed Ruscha restaged Cole’s series with his own ‘Course of Empire’, exhibited in the American Pavilion at the 51st Venice Biennale. Ruscha’s ten paintings show the broken suburbs of LA and the ruins brought about by thoughtless consumer culture, where regional workshops are replaced by epic warehouses for imported goods. Those goods are made in special economic zones (ie, in gothic conditions) such as the Northern Mariana Islands, territories administered by the US since 1947 and, as Immerwahr describes, used to pilot the modern sweatshop. From Cole to Ruscha to Hollywood: time and time again America gazes at its navel and wrings its hands. Has the US been a good leader, spreading the good capitalist gospel, or a slave-trading, imperialist, racist empire, with blood on its hands? That is the problem with staging the death of the US; so often it feeds American narcissism, giving an audience to the nation’s psychodrama as it lies back on the couch.

In his 2012 short story Certain Fathoms in the Earth, Chris Sharp examines the US as a culture obsessed with images of its own decline. His narrator is a future Chicxulub survivor, sifting through America’s ruins and piecing together its final decades. ‘All of their energy seemed to go into the production, accumulation and indiscriminate distribution of images,’ the narrator reports. ‘Nothing, no form of image, it is said, thrilled them more than those of their own end. They produced them by the thousands, possibly the millions. Legend has it that an entire culture evolved around this end-ism … nothing intoxicated them more than the complete and total annihilation of the great New York.’

America’s narcissism continues. The latest episode in the apocalyptic drama is the presidential election, for which the US staged its death yet again. In the run up to 2 November, as Vō’s flag dwindled and burned, US commentators began to sound the Chicxulub alarm. In an article titled ‘The end of democracy?’, the Washington Post predicted doom, whatever the electoral outcome. The event played out far better than CNN or Fox News could have hoped, in six days of riveting, nail-biting television – with Trump’s false declaration of victory followed by night after night of vote-counting, the figures updated on some news sites every 15 seconds. It had the flavour of a game show combined with the juiciest reality TV, with all cameras on Trump, its practised, monstrous star. Has democracy died? Was the election really so different to the last one? More likely it is as Vō suggests: that Chicxulub is a repeated event, one that has previously recurred across various colonised countries, outside the news feed, and is now happening, on screen, in the US.

The difference is that, unlike those invasions in Vietnam or Iraq, when the US stages its own death it happens on the level of the image – not so much a death blow as a box-office hit. The US watches itself die its intoxicating image-death, ‘symbolically destroyed time and time again’, as Sharp writes, ‘in a paroxysm of apocalyptic ecstasy’.

Izabella Scott is a writer and researcher based in London. She is an editor at The White Review.

First published in Art Monthly 442: Dec-Jan 20-21.